2020.07.17 | By Gregory Nagy

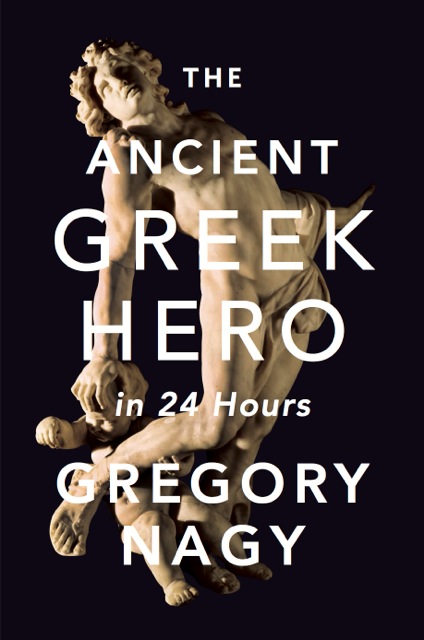

§0. In this brief essay, I talk about a book that can help get you started if you wish to make a personal commitment to read the Homeric Iliad, all of it, in translation. It is a book of mine that was first published in 2013 by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press under the title The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Thanks to the Press, this book is also available online, for free. Alternatively, readers can order, from Harvard University Press, an abridged second edition of the printed version, published as a paperback in 2020. And how is this book helpful to those who are tempted to read the Iliad of Homer? In my essay, I claim that the illustration on the cover of the book, in both the printed and the online versions, offers a good answer. To say it another way: sometimes you can in fact judge a book by its cover.

§1. What we see being pictured here is the ancient Greek hero Achilles, dying of an uncurable wound. He has been shot, mortally wounded in his “Achilles Heel” by an unerring arrow that was aimed at him, with deadly accuracy, by a skilled archer, the rival hero Paris, also known as Alexandros, who was aided by Apollo, god of archery. This same Apollo, who is the divine body double of Achilles, is the god in charge of so many other things that are linked with the dying hero, including the music and the singing and dancing of the Muses. According to one myth, Apollo in his role as choreographer of the Muses is also the father of the mythologized Homer who sings the song of Achilles in the Homeric Iliad. Attending Achilles at the moment of his beautiful death—the French call it his belle mort—is a “Cupid” (in Greek, such a cupid is called an “Eros”). This “Cupid” is trying in vain—maybe all too half-heartedly—to extract the deadly arrow from the hero’s mortal wound.

§2. Here is a set of five built-in questions that I ask myself about what we see being pictured here:

(1) What is the symbolism that seems be operating in this picture?

(2) Why is the mortal wound of Achilles, who has just been wounded in his “Achilles Heel,” linked with Eros, who is the incarnation of eroticism?

(3) Why would I (GN), as the author of a book about ancient Greek heroes, choose for the cover of this book a picture that links Eros with the death of a hero?

(4) Most important, where do we find the “Achilles Heel” of Achilles when we are reading the Homeric Iliad?

(5) A different way of asking the fourth question is this fifth question: what is the “Achilles Heel” of Achilles in the Homeric Iliad?

§3. My way of thinking about an answer, or, better, about the best possible answer for Question Five can be summed up most simply: You will not be able to answer this question without having read all the Iliad.

§4. To my mind, the best answer to my Fifth Question was formulated not by me but by a Harvard College student in an essay written after this student had finished reading the Iliad for the very first time. This particular student, like the vast majority of persons who have taken or audited my course about the ancient Greek heroes over the years, did not know Greek and was reading the Iliad only by way of an English-language translation.

§5. But here is where my mind fails me: I cannot for the life of me remember who the student was and when this person took my course about ancient Greek heroes. All I recall is that it happened long ago, a very long time ago. The one thing I do remember, though—and here my mind does not fail me—is the actual answer that this person formulated. I have total recall of that answer, but I don’t want to spoil the impact of the answer by revealing it to those who have not yet committed to their first-ever reading of the Homeric Iliad. Even in translation, though, the answer will leap at you.

§6. That said, I must now admit, in the same breath, that the answer I have in mind may not be the very best of all possible answers. All I am saying is that it’s the best answer, to my mind. And I must now add: maybe some new reader will come up with a new answer that is even better than the old answer. Who knows?

§7. In this brief essay, I have added in the margins some annotations pointing to places in my other online publications where I have already thought about the wordings that I use here. Some of these places, indicated by the annotations that function as placeholders, involve simply the relevant words, while, in other places, I show pictures that evoke what I am still trying to put into words.