2021.01.29 | By Gregory Nagy

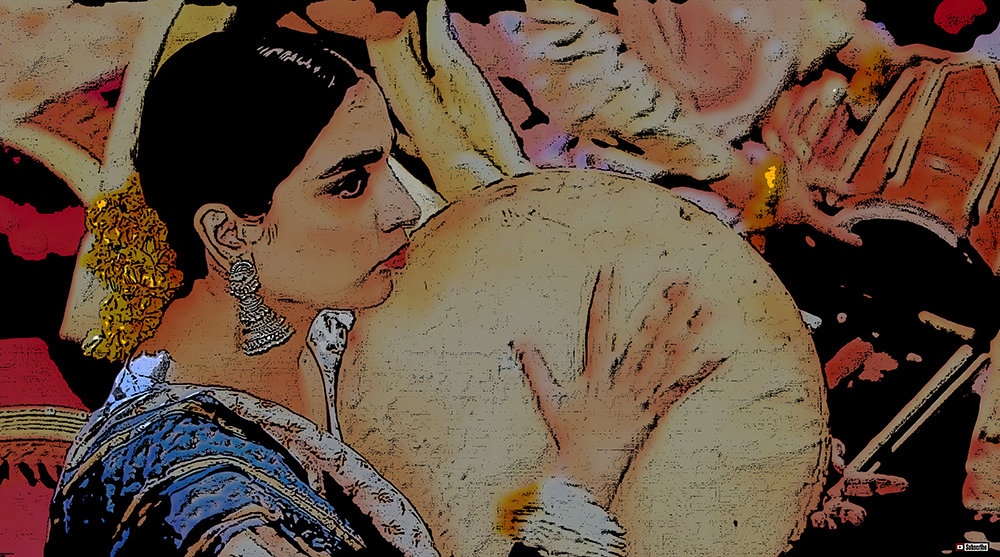

§0. This brief essay considers a situation where girls and women are having an all-night party in celebration of a bride who is getting married tomorrow, let us imagine. In previous essays, I have analyzed references, in a wide variety of ancient Greek texts, to such all-night partying, and I tried not to lose track, in these essays, of the facts of life. I am fully aware that such merriment, to be enjoyed by girls and women, can lead to suspicions of a kind of sexuality that may be deemed to be improper by, say, judgmental elders. But what if we consider the self-expression of the bride herself on the occasion of an all-night party where she celebrates, with other girls and with older women—including, presumably, not only her own female friends and relatives but also her future female in-laws—the upcoming “happy” event of her wedding? It would be wrong-headed, I think, to assume that only ‘courtesans’, say, as suggested by the ancient Greek word hetairai, could find it possible to express their own sense of sexuality—or, we could call it sensuality—at all-night parties. I argue that a bride, through such media as we see surviving in Sappho’s songs, for example, could be imagined as a diva who sings her own sexuality—not just singing about it but even singing it—on the occasion of her very own “all-girl” wedding party lasting all night long. The songs of Sappho reflect here and there, as I have argued in previous essays, such self-expressions of sexuality, sensuality. And there are further reflections, as I have also argued, both in later pieces of verbal art that are reminiscent of Sappho and even in later pieces of visual art, as in pictures painted by the so-called Meidias Painter in the classical era of Athens. A case in point is the female beauty Pannychis, whose very name personifies such all-night partying and whom the Meidias Painter pictures in the act of beating out on her tambourine the rhythm of her song, aiming her sensual beat at an ecstatically dancing cupid or Eros. Only such diminutive male Erotes, as also pretty-boys like Adonis or Phaon, are admitted to such a mythologized “all-girl all-nighter.” And another case in point is a modern parallel, shown here in two consecutive freeze-frames extracted from a film about a bride who takes charge of her own singing at her own wedding party. Singing her song, she inspires her girl-friends or would-be girl-friends to “beat the drums with full vigor and sing with me.”

§1. If we look for ancient Greek texts that refer to all-night partying by girls (accompanied or not by older women) in celebration of a girl-friend who is about to become a bride, a good place to start reading, I think, is a set of two passages in Pythian Ode 3 of Pindar, as I argued in a previous essay (Nagy 2015.12.3 §3, linked here).

§1a. In the first of these two passages, the merry wedding songs sung for a bride by her girl-friends are described this way:

|17 . . . ἅλικες |18 οἷα παρθένοι φιλέοισιν ἑταίρᾳ |19 ἑσπερίαις ὑποκουρίζεσθ᾽ ἀοιδαῖς

. . . just as girls [parthenoi] who are age-mates [of the bride] love to do sweet-talk [hupo-kor-izesthai] in their songs sung for their companion [hetairā = the bride], come evening.

Pindar Pythian 3.17–19

Alternatively, if we read ἑταῖραι instead of ἑταίρᾳ in the original Greek text, we can translate:

. . . just as girls [parthenoi], companions [hetairai] who are the same age [as the bride], love to do sweet-talk [hupo-kor-izesthai] in their songs sung, come evening.

§1b. At a later point in the same song, Pythian Ode 3 of Pindar, a mother goddess is described this way:

|78 . . . τὰν κοῦραι παρ᾽ ἐμὸν πρόθυρον σὺν Πανὶ μέλπονται θαμὰ |79 σεμνὰν θεὸν ἐννύχιαι . . .

. . . that venerable goddess, whom the girls [kourai] at my portal, with the help of Pan, celebrate by singing and dancing [melpesthai] again and again [thama] all night long [ennukhiai]. . . .

Pindar Pythian 3.78–79

§2. But what about the bride? Will we get to see her sing for herself? The closest thing, perhaps, to such a festive scene would be a situation where the songs of Sappho herself are being sung by girls at an all-night wedding party. In Epigram 55 of Posidippus, we almost get to see such a scene of a singing bride. But, sadly, the bride is no longer there, since this would-be diva of the all-night-partying has died prematurely. I quote here the text and the most recent version of my working translation (Nagy 2016.01.07 §2, linked here):

|1 πάντα τὰ Νικομάχηϲ καὶ ἀθύρματα καὶ πρὸϲ ἑώιαν |2 κερκίδα Ϲαπφώιουϲ ἐξ ὀάρων ὀάρουϲ |3 ὤιχετο Μοῖρα φέρουϲα προώρια· τὴν δὲ τάλαιναν |4 παρθένον Ἀργείων ἀμφεβόηϲε πόλιϲ, |5 Ἥρηϲ τὸ τραφὲν ἔρνοϲ ὑπ’ ὠλένοϲ· ἆ τότε γαμβρῶν |6 τῶν μνηϲτευομένων ψύχρ’ ἔμενον λέχεα.

|1 Everything about Nikomakhe, all her pretty things and, come dawn, |2 as the sound of the weaving pin [kerkis] is heard, all of Sappho’s love songs [oaroi], songs [oaroi] sung one after the next, |3 are all gone, carried away by fate, all too soon [pro-hōria], and the poor |4 girl [parthenos] is lamented by the city of the Argives. |5 She had been raised by the goddess Hera, who cradled her in her arms like a tender seedling. But then, ah, there came the time when all her would-be husbands, |6 pursuing her, got left behind, with cold beds for them to sleep in.

Posidippus Epigram 55

§3. This epigram, as we can see, is about a girl whose happy young life was sadly interrupted by a premature death. Nostalgically, the words of the epigram recall all the merriment—all the happy times when this girl and her girlfriends were singing the love songs of Sappho, sung one after another. That is what I argued in my earlier postings (Nagy 2015.11.19, 2015.12.03, and 2016.01.07, here and here and here). But now I argue further that such love songs could have been sung also on premarital occasions like the parties where the bride can sing, without inhibition, to girl-friends or would-be girl-friends: “beat the drums with full vigor and sing with me.”

§4. Epilogue. I am grateful to Seton Augusta Uhlhorn for introducing me to the “clip” that is linked (“Dua-e-Reem“) in the captions written under the first two pictures shown in this essay.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.