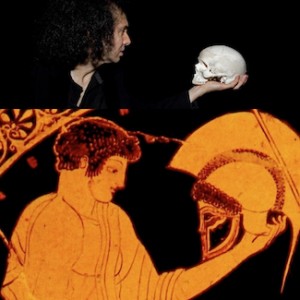

Neoptolemos/Pyrrhos holding the helmet of Achilles as he receives the armor of Achilles from Odysseus. 490-480 BCE, by the painter Douris. Vienna 3695

Introduction

I continue from where I left off in Classical Inquiries 2017.12.14. From 1.11.1 to 1.13.8, there is a lengthy narrative about Pyrrhos-son-of-Aiakidēs (the latinized spelling of his name is Pyrrhus), king of Epeiros, whose lifespan dates from 319/8 to 272 BCE. This Pyrrhos was world-famous for his many military successes, including victories in his war against Rome after he invaded Italy in 280 BCE—though the heavy losses suffered by his forces in their encounters with the Romans, as narrated for example in Plutarch Life of Pyrrhos 21.9, led to a proverbial expression that is still current today, “Pyrrhic victory.” Before he narrates the story of Pyrrhos, however, Pausanias presents other historical narratives that extend from 1.8.2 all the way to 1.11.1. {1.11.1} translation by Jones 1918, modified by GN 2017.12.21:Such were the things that happened in connection with Lysimakhos. The Athenians have also a likeness [eikōn] of Pyrrhos. This Pyrrhos was not related to Alexander, except by way of genealogy [genos]. Pyrrhos was son of Aiakidēs, son of Arybbas, but Alexander was son of Olympias, daughter of Neoptolemos, and the father of Neoptolemos and Arybbas was Alketas, son of Tharypos. And from Tharypos to Pyrrhos, son of Achilles, are fifteen generations [geneai]. Now, Pyrrhos was the first who after the capture of Troy disdained to return to Thessaly, but sailing to Epeiros dwelled there following the oracular-pronouncements [khrēsmoi] of Helenos. By Hermione Pyrrhos had no child, but by Andromache he had Molossos, Pielos, and Pergamos, who was the youngest. Helenos also had a son, Kestrinos, being married to Andromache after the killing of Pyrrhos at Delphi.

{1.11.1} subject heading(s): Pyrrhos the hero, Pyrrhos the king Pausanias at 1.11.1 begins here his narrative about Pyrrhos-son-of-Aiakidēs, king of Epeiros. I have already noted that Pyrrhos claimed as his ancestor, counting twenty generations backward in time, the Greek hero Pyrrhos-son-of-Achilles. (Pausanias complicates the numbering by starting with an ancestor that goes five generations back and then adding fifteen generations more.) This hero was otherwise known as Neoptolemos, meaning ‘renewer of war’. As for his name Pyrrhos, it means ‘fiery red’. Both names are most apt, because the hero Pyrrhos/Neoptolemos is traditionally pictured in the verbal and visual arts of the ancient Greeks as a veritable killing machine—whose fiery temperament in war replicates and thus renews the deadliest wartime moments of his father. In the case of Achilles, we find a horrific example of such a moment at Iliad 21.328–384, where the hero goes berserk as he proceeds to slaughter, one after the next, all the fleeing Trojan warriors whom he overtakes in his murderous progression of martial fury: the more blood he spills, the more furious he gets—until he becomes the embodiment of fire itself, since the poetry of the Iliad now merges this warrior’s rage with the cosmic power of Hephaistos as the god of raging fire. In the case of Pyrrhos/Neoptolemos, such horrific moments of martial fury are further augmented and multiplied: examples include the fiery hero’s slaughtering of Priam the old king, of Polyxena the beautiful princess, and of prince Astyanax, hapless child of Hector and Andromache.

Bibliography See the dynamic Bibliography for APRIP.

Inventory of terms and names See the dynamic Inventory of terms and names for APRIP.

Notes Cover image credit: Image via; shared there and distributed here in modified (cropped) form under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.