2021.02.13 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. In this brief essay, I consider again the beautiful sandals worn by the girl from Lesbos who is described in a song of Anacreon that I analyzed in my previous essay for Classical Inquiries (Nagy 2021.02.06). Even though the poetic dialect of Anacreon is Ionic, the sandals worn by the girl are described in this song with a word that is shaped in the Aeolic dialect of Sappho. I argue that we see here a Sapphic “signature” for these sandals, signaling that the girl is pictured as dancing, and that she is dancing in a way that girls are imagined as dancing in the songs of Sappho—whether or not they are wearing sandals.

§1. The Sapphic “signature,” as I call it here, can best be visualized when we view the many surviving varieties of ancient perfume-bottles, aryballoi, that are shaped like a human foot wearing a pretty sandal. I cannot help but admire the handicraft of the leatherwork that is represented by the potters who manufactured these bottles made of terra cotta. I highlighted in the previous essay (Nagy 2021.02.06 §11, linked here) the wording that describes such luxuriant leatherwork in a song of Sappho (F 39), where we see a girl pictured as wearing sandals held together by beautiful leatherwork, of luxuriant Lydian manufacture, which is described as poikílo-, ‘pattern-woven’: πόδας δὲ ποίκιλος μάσλης ἐκάλυπτε, Λύδιον κάλον ἔργον ‘her feet were hiding under pattern-woven [Aeolic poíkilo-] footwear [maslēs], beautiful handiwork, made in Lydia’. As I argued in that essay, the adjective poikílos (Aeolic poíkilos/ποίκιλος), as we see here in the wording of Sappho, signals the eroticism of a girl’s pretty feet in motion, as she dances. I see such eroticism made explicit in Song 16 of Sappho, where the female speaker yearns to see, once again this time, the ‘lovely step’ (ἔρατόν … βᾶμα, line 17) of a missing girl, Anaktoria: she is now gone, no longer to be seen, but the fond vision of her gracefully dancing feet can be revisited again and again in song.

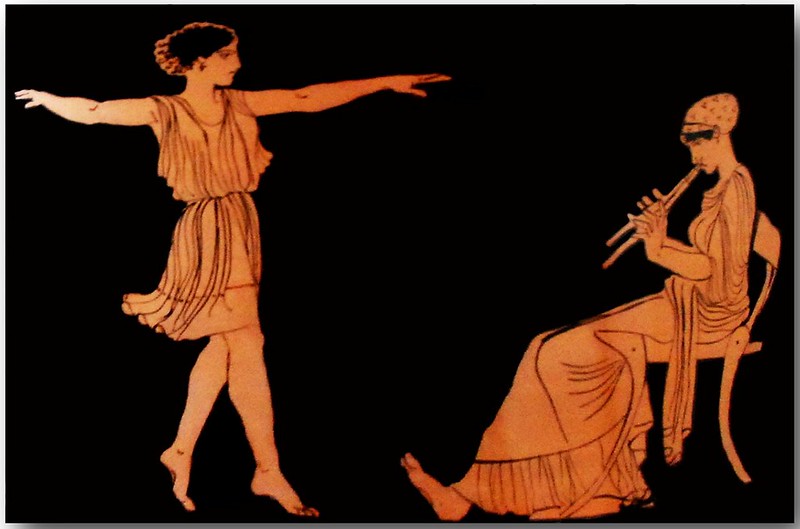

§2. My colleague Natasha Bershadsky points me to a most relevant essay that had escaped my notice till now. Coincidentally, it was written by an old friend and colleague of mine, Daniel Levine (2005). In Levine’s essay, he too highlights the eroticism of the girl’s pretty feet in Song 16 of Sappho, and his highlighting connects the loveliness of this detail with a wide variety of comparable mentions, in all their dazzling variety, of pretty feet that are aestheticized and occasionally even fetishized in the ancient world. My contribution to Levine’s admirable survey of all these mentions is simply this: in such cases as Song 16 of Sappho, the pretty feet of Anaktoria are pretty not only because the girl is naturally beautiful. Her feet are pretty also because her beauty, which is a thing of nature, is fused with a thing of culture, which is the beauty to be seen in the art of dancing. I am speaking here in anthropological terms, where I focus for just a fleeting moment on the well-trodden dichotomy of “nature” and “culture.” In terms of my argument, the girl is envisioned as dancing inside the mental space of a memory conjured by the song, and the graceful steps of her dancing feet are beautiful to see. The beauty here is to be found not only in the human body, as when you look at a girl’s beautiful feet and view the beautiful way she walks: it is to be found also in the beautiful way her body is activated in the act of dancing—while she is presumably singing as well, since her eraton bāma or ‘lovely step’, the radiant sight of which has been sadly lost and longingly missed in Song 16 of Sappho, is a vital aspect of choral performance, which in ancient Greek terms is an organic fusion of dancing with song. Such a fusion of song and dance is actually embodied, I think, in the singing of Sappho.

§3. As for the dancing of a girl like Anaktoria, as I argued in the previous essay (again, Nagy 2021.02.06 §11, linked here), it is signaled in the song of Anacreon about a pretty girl from Lesbos. The word describing this girl is a compound adjective, ποικιλοσαμβάλῳ at line 3 of Anacreon’s song (F 358 in PMG ed. Page), which can be translated as ‘wearing sandals [sámbala] that are pattern-woven [poikíla]’. In the Ionic dialect, the noun that we translate as ‘sandal’ is either sándalon, plural sándala (as in Homeric Hymn to Hermes 79, 83, 139), or sandálion, plural sandália (as in Herodotus 2.91). What I formulate here for Ionic applies also to the Doric dialect, as we see in Idyll 24 of Theocritus (line 36), σάνδαλα ‘sandals’ and in the Lament for Adonis by Bion (line 21), ἀσάνδαλος ‘not wearing sandals’. Similarly in a choral ode of the Iphigeneia in Aulis by Euripides, we read χρυσεοσάνδαλον ἴχνος ‘footprint of a golden sandal’. In the Aeolic dialect of Sappho, by contrast, Ionic and Doric sándala are sámbala, as in Sappho Fragment 110a (line 2), where we read σάμβαλα. What I find most remarkable, then, about the sandals worn by the dancing girl in the song of Anacreon is that her footwear is Aeolic footwear linked with dancing. Thus her sandals are linked with the Aeolic songs of Sappho.

§4. But you don’t have to wear sandals just because you feel like dancing Aeolic-style. When you feel like dancing with abandon, as when you become a maenad, you dance barefoot. In Ionic and Doric, the appropriate word would be ἀσάνδαλος/asándalos, ‘not wearing sandals’, as we have already seen in the Lament for Adonis by Bion (line 21). And if you do dance barefoot, you can still dance Aeolic-style. In the Aeolic dialect, the appropriate word would be ἀσάμβαλος/asámbalos. Such a style, I argue, must have been signaled in the songs of Sappho, though I can find no direct attestations. But I can find a wealth of indirect attestations in poetry that reflects an ongoing reception of Sappho’s songs. A shining example is a lengthy poem about Dionysus, the Dionysiaka, composed by Nonnus of Panopolis, who lived in the fifth century CE. In his poetry, Nonnus pictures a typical maenad, uninhibited devotee of Dionysus that she is, as a girl gone wild, as it were, since she has let down her flowing hair, having undone her headdress, and has slipped out of her sandals as she dances barefoot in the wilderness with sensual abandon (Dionysiaka 14.381–383):

ἦν δὲ νοῆσαι | παρθένον ἀκρήδεμνον ἀσάμβαλον ὑψόθι πέτρης | τρηχαλέῳ πρηῶνι περισκαίρουσαν ἐρίπνης·

[And, as you view the maenads], you could spot | some girl, who is not-wearing-her-headdress [akrḗdemnos] and not-wearing-her-[Aeolic]-sandals [asámbalos], [and there she is,] high up there on the rocky heights looming above, | dancing-around at the jagged edge of a steep rock face.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.