2020.10.30, rewritten 2020.11.05–12 | By Gregory Nagy

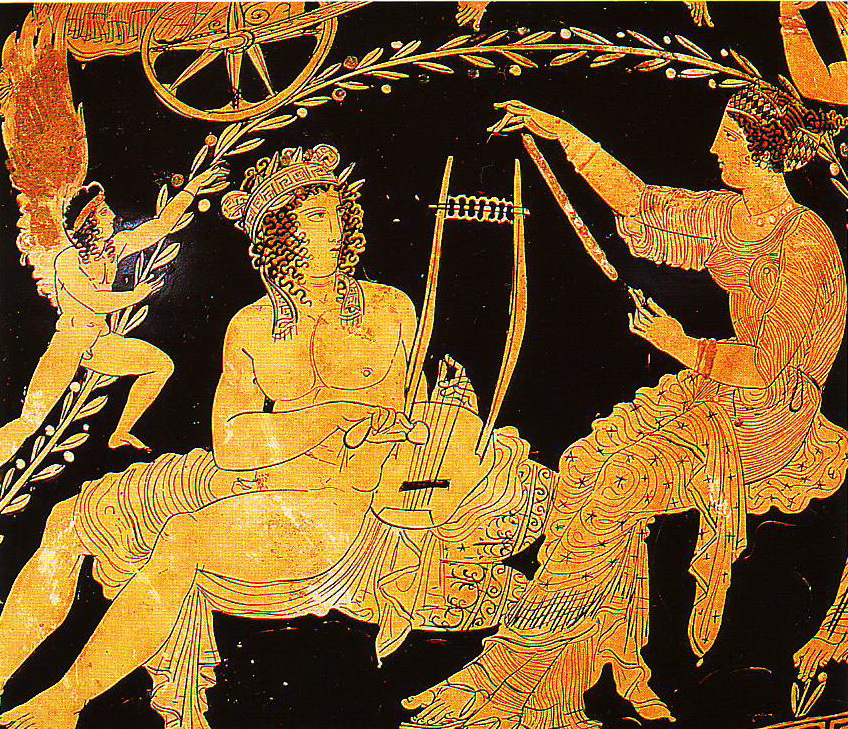

§0. In this essay, I am not looking for references to the text of Sappho’s songs in Athenian vase paintings. Instead, I look merely for traces of pictorial references to the contents of these songs, especially as performed in the city-state of Athens during the classical period, in the fifth century BCE and beyond. In other words, I am looking for aspects of Sappho’s songs that Athenians of that era would have remembered from hearing these songs being performed at symposia and even at public concerts—especially at the festival of the Great Panathenaia. But we are faced with a problem whenever we consider more closely this kind of remembrance by audiences—and even by the painters who were surely part of such audiences. Just as the painters of classical Athens, masters of their visual art, would have tuned in, as it were, to the masters of verbal art who transmitted, in performance, the songs of Sappho, these painters would have been no different from the general audiences if they also remembered many other kinds of relevant songs besides those of Sappho, and their references to any and all such songs in any single painting would not need to be compartmentalized. So, whenever we happen to see in any given painting some detail that corresponds to a detail we read in a surviving text of Sappho—or even in some later text where Sappho is being imitated—we cannot really expect such painted details to be restricted to any single song attributed to Sappho or to any other maker of songs, as if such a song were merely a text. Instead, we do need to expect, in any given painting, a possible mixing of different details heard in different songs. Such mixing, however, would not disprove the reality of references actually made in visual art to specific details that would be heard in verbal art. As my first example of such a reality, I show here a close-up from an Athenian painting that dates back to the fifth century BCE.

§1. I proceed to examine this close-up in the light of the overall painting, which the reader may view by consulting the available images in the Beazley Archive. The link to this resource is signaled in the caption immediately above. In the close-up that I show here, we see pictured the youthful hero Phaon, renowned for his beauty and made famous in the songs of Sappho—his identity is guaranteed by the lettering ΦΑΩΝ (not visible in the close-up), placed next to the painted figure. Phaon is shown playing his music on a lyre while sitting inside a luxuriant bower and enjoying the attentive company of a lady named Demonassa, who is identified by way of lettering similarly placed next to her beautiful figure. There is no question here, to my mind, that this Phaon is Sappho’s Phaon. As I have shown in ongoing research (starting with Nagy 1973, and most recently, in Nagy 2020.09.04), Phaon was featured as a primary love object for Sappho—that is, for her poetic persona. For Sappho, Phaon was an ultimate emblem of unrequited love, and this aspect of Sappho’s poetics is still most clearly visible in the Ovidian poem Heroides 15. But who was Demonassa? Was she too featured in the songs of Sappho? Given the sadly fragmentary state of the textual tradition of Sappho, we cannot be certain: she may have been a figure in songs of Sappho that are lost to us—or maybe not. But my point is, her presence in the painting is in any case relevant to the poetics of Sappho, as we can see from the context of the overall painting from which I have highlighted this close-up.

§2. The context of the overall painting, as described here, highlights an amorous atmosphere enjoyed by an ensemble of ladies pictured in the painting, including Demonassa. The amorousness of these ladies is explicitly signaled by the presence of the goddess of love incarnate, Aphrodite herself: she is shown driving a chariot drawn by two naked adolescent ‘cupids’ or eros-figures, whose names here are Himeros and Pothos, both meaning ‘longing, desire’. Here is a close-up of Aphrodite and her ‘cupids’:

§3. The ensemble of other ladies represented in the overall painting are identified, just like Demonassa, by way of lettering placed next to their beautiful figures, and their names are listed in the commentary provided by the Beazley Archive, signaled in the caption I provided at §1 above: they are Hygieia, Eudaimonia, Leura, Chrysope, Erosora (ΗΡΟΣΩΡΑ), and Pannychis. At a later point, I will focus on the last of these names, but, for now, it is enough for me to emphasize that the association of these ladies with Aphrodite in the visual art of this painting is relevant to the association of Sappho’s Phaon with this same goddess in the verbal art of Sappho, where our beautiful hero is the love-object of Aphrodite herself. It is, in fact, this amorous role of Phaon that makes him a concurrent love-object of the Sapphic persona, as I have argued in my earlier work (especially in Nagy 1973).

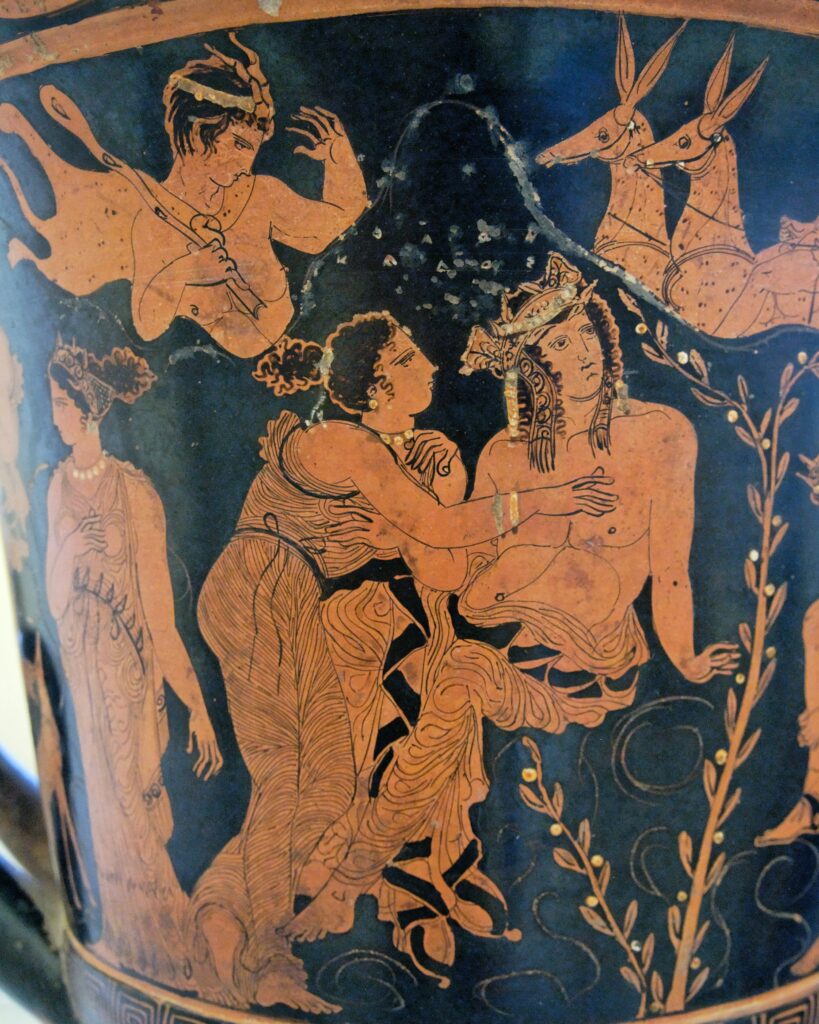

§4. And now I show a close-up from another Athenian painting that features Phaon in the amorous company of ladies, one of whom is preparing to embrace him. The lettering next to Phaon says ‘Phaon is beautiful’ (ΦΑΩΝ ΚΑΛΟΣ).

§5. Besides Phaon, another love-object of the goddess Aphrodite is the beautiful youthful hero Adonis, as pictured in another related Athenian painting:

In this picture, we see Adonis (the lettering says ΑΔΩΝΙΟΣ) embraced from behind by Aphrodite (ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΗ) on our right while on our left he is being prompted into erotic action by a winged Eros named Himeros ‘longing, desire’ who is hovering overhead. Further to our left, an attending lady named Eurynoe (ΕΥΡΥΝΟΗ) is teasing her pet bird by provoking it to peck at her pointed index finger. Such a picturing in the visual art of this painting is matched by comparable visualizations in the verbal art of song and poetry, as for example in Poem 2 of Catullus, where ‘the girl from Lesbos’, Lesbia, is pictured in the act of playfully provoking her pet sparrow to peck at the tip of her index finger. As I argued in another project (section E of Nagy 2019.03.08), the pet bird pecking at the fingertip of Lesbia in Poem 2 of Catullus may have been modelled on an erotic image that originated—indirectly or perhaps even directly—from a now-lost song of Sappho. Perhaps the pet bird in the image painted by the Meidias Painter is an earlier example of such modelling.

§6. And then, painted on this same Athenian vase, we see again a lady by the name of Pannychis:

Although the lettering that matches this figure is fragmentary, the lady’s name is evidently Pannychis ([ΠΑ]ΝΝΥ[ΧΙΣ]), and she is one of an ensemble of ladies attending the amorous Aphrodite and Adonis. The ladies, as indicated by the letterings, are Eutychia, Eudaimonia, Hygieia, Paidia, Pandaisia, and Eurynoe (ΕΥΡΥΝΟΗ).

§7. So, where do we go from here? For me, the beautiful figure of Pannychis, viewed in the last picture I have shown in this preliminary essay, gives us viewers her own special gift of a possible response. When I was reading through the commentary in the Beazley Archive as cited in my caption for the illustration that I show at §5 above, I couldn’t help but notice a common thread of thought running through the overall painting that highlights this figure of Pannychis, revealed here in all her beauty. And I am hardly the only viewer who has picked up on this thread. Like me, a number of the commentators cited in the Archive view this figure Pannychis as some kind of a divine personification. Such a way of viewing Pannychis makes sense to me. I find it most relevant that our beautiful Pannychis, as pictured in this exquisite painting, is seen in the act of making eye-contact with the male personification of erotic longing, desire—and he is none other than the beautiful boy Eros, named here Himeros, which actually means ‘longing, desire’. Pannychis is fixing her gaze downward at the divine boy, and he is looking upward, eye to eye, matching with his own gaze her looks of love.

§8. The beautiful Pannychis of this painting matches the comparably beautiful Pannychis of a related painting that I already cited at §1 above, referring to the relevant commentary in the Beazley Archive, here. As I then went on to add at §3, citing the same commentary, Pannychis in that painting is accompanied by the following beautiful ladies, each named by way of adjoined letterings: Hygieia, Eudaimonia, Leura, Chrysope, Erosora, and Demonassa. Two of the names for those companions of Pannychis as listed at §3—Hygieia and Eudaimonia—are matched in the group of her companions as listed at §6.

§9. The ladies who accompany the beautiful Pannychis in both Athenian paintings considered here are I think divine personifications, as we see clearly in the case of Hygieia and Eudaimonia, for example, whose names indicate fond wishes for ‘[good] health’ and ‘good fortune’ respectively. That is their literal meaning. And Pannychis herself, as I suggested already at §7 above, must be in her own right a divine personification of something related to such fond wishes. But what is that something? For a possible answer,I turn to the songs of Sappho, where the verb pannukhizein, which I propose to translate as ‘have a merry time all night long’, is actually attested (παννυχισδο.[.]α̣.[…] in Fragment 30.3 and [παν]νυχίσ[δ]ην in Fragment 23.13).

§10. In Epigram 55 of Posidippus, as I argued in another essay having to do with Sappho (Nagy 2015.12.03), there is a reference to a custom of singing love songs of Sappho on the occasion of all-night parties enjoyed by unmarried girls. I suggest that Pannychis is a personification of this merry premarital custom. And the ideal model for such all-night partying would hardly be some everyday girl supervised by some everyday mother who is hoping to marry her off to some everyday suitor, as Mrs. Bennet hopes to marry off her eldest daughter Jane in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813). No, the ideal model would be the divine Persephone, supervised by her divine mother Demeter. Such a model is echoed in the words of Aristophanes in Frogs 447, picturing a festive moment at the grand all-female Athenian festival known as the Thesmophoria: οὗ παννυχίζουσι θεαί ‘where the [two] goddesses celebrate-their-all-nighter [verb pannukhizein]’. The comment made on this wording in scholia derived from Tzetzes (12th century CE), who reads θεαί ‘the [two] goddesses’ instead of θεᾷ ‘to the goddess’ (both variant readings θεαί and θεᾷ are attested in the manuscript tradition), seems to me most apt: οὗ ἡ Κόρη καὶ ἡ Δημήτηρ χορεύουσι, χαίρουσι, παίζουσι, παννύχιον ᾄδουσιν ‘where the Girl [Korē = Persephone] and [her Mother] Demeter sing-and-dance [khoreuein], take-pleasure-in-the-beauty [khairein], get-playful [paizein], and make-song [āidein] that lasts-all-night-long [pannukhion]’. Such a “[girls’] all-nighter,” to say it in American popular language, is the essence of pannukhis, an ‘all-night’ merriment divinely personified as Pannychis.

Epilogue

I am eager to put on record my profound appreciation for all the generous help I have received from my dear colleague and friend Natasha Bershadsky in the course of my struggling to produce a preliminary write-up of the comments offered in my essay here. Natasha’s perceptive insights in her own explorations of relevant images and commentaries as made available in the online Beazley Archive have been a steady guide for me. The captions that the reader finds embedded within the paragraphs of my essay refer to some but hardly all of the relevant images. I hope that Natasha will share her further insights by adding annotations to my captions, not only to my paragraphs. That way, the epilogue here can be turned into a prologue for further study.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.