June 11, 2021[1] | Renée S. Landzberg

1. Introduction

§0. Concepts of femininity from the Classical period pervade deeply through the Classical era of classical music, latter epitomized by the composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It is not surprising then to see parallel traits in the mythological construct of Hērā, Queen of the Gods, and the Queen of the Night from Mozart’s hugely popular opera, The Magic Flute. A longstanding fascination with the classical period and of classical mythology is obvious in other Mozartean operas, including Apollo et Hyacinthus (composed at age eleven), La Clemenza di Tito, and Idomeneo, Re di Creta. Specifically, in the personae of Hērā and the Queen of the Night, we see classical and neo-classical conceptions of femininity including motherhood, capricious and unpredictable emotionality, melancholy, raging temper, and jealousy. This duality of loving maternalism and uncontrollable, vengeful rage comes through in the marked juxtaposition of the Queen of the Night’s two signature arias, “O Zittre Nicht, Mein Lieber Sohn” and “Der Hölle Rache.”

2. Athenian Concepts of Women

§1. Although Plato was more enlightened about the potential idea of female equality, in Politics Aristotle wrote “as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject.”[2] Women were biologically “mutilated males” who must be kept under male rule and protection as they lack not only physical strength, but mastery of their own emotions. Their anatomy suited them to the gestation and suckling of motherhood and there was little need for them to pursue other roles. Aristotle felt that the deliberative faculty in women is ‘without authority’ or akuron, so that women needed to be under the stabilizing and steering influence of men.[3] When Sarastro, High Priest of the Sun, speaks to Pamina, the Queen of the Night’s daughter, he almost quotes Aristotle: “Ein Mann muss eure Herzen leiten, Denn ohne ihn pflegt jedes Weib Aus seinem Wirkungskreis zu schreiten.”[4] Translated: ‘a man has to lead your heart because without a man, every woman tends to step out of her sphere’. These associations can be seen in the construct of the goddess Hērā. The emotionally labile and vengeful goddess hated and sought to destroy an entire people of Trojans solely for being spurned by their prince in a beauty contest. Her murderous rage found its most frequent victims in Zeus’s lovers and the offspring of his affairs, including Semele, Dionysis, and many others. On the other hand, according to one version of the myth, Hērā took maternal pity on Hēraklēs, whom she believed to be an abandoned child, and breastfed him. This act of loving maternalism, however, would be followed by an explosion from her breast that created the milky way in the heavens and a future of tormenting Hēraklēs the remainder of his life. Hērā would swing between saving mother and angry avenger.

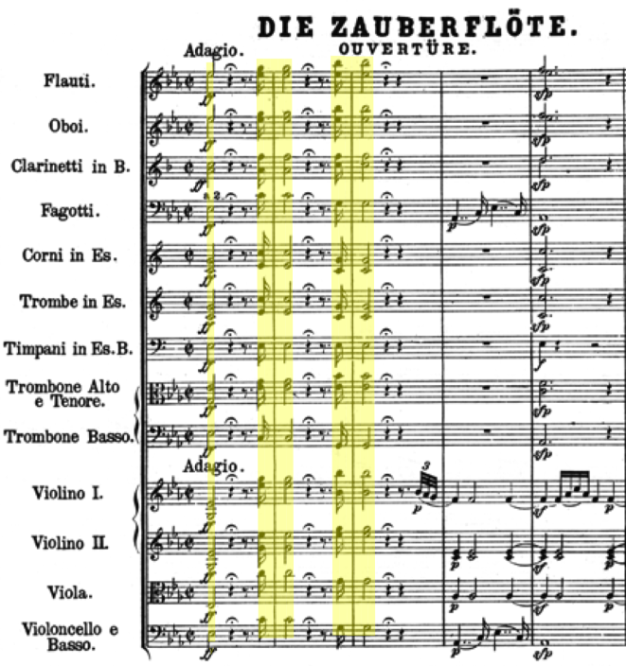

§2. In looking at classical Greek underpinnings to the Queen of the Night, one can also consider the Greek association of the female with darkness and the moon. Although Hērā was not personally associated with the moon (though the Roman Juno was), the Greek deities associated with the moon are all goddesses, including Selene, Artemis, and Hecate, while the sun god, Apollo, was male. The monthly menstrual cycles of women would also make it natural to associate femininity with the moon and its monthly cycle. Ancient Chinese concepts of yin and yang show the same dualism, in which Yin correlates with the moon, darkness, femininity, and a need to be led or controlled, while the more active Yang, is correlated with the sun, light, masculinity, and controlling personalities. Among the many mythical sources of inspiration for The Magic Flute are Arthurian fairy tales and Egyptian myths, as well as Freemasonry, a male society of which Mozart was a devoted member. Enlightenment, reason, brotherhood, and Egyptian motifs are all part of masonic ritual, as is the commencement of a ceremony with three knocks, which is interestingly evoked by the tympani and orchestra’s unison playing of a half note and two couplets as the opening notes of The Magic Flute’s overture.[5]

The opera, or more correctly singspiel, is allegory for the quest for light, truth, and virtue, while the Queen of the Night, and femininity in general, is depicted as the antithesis.

3. Mozart’s Personal Life

§3. In Mozart’s own life, several strong women likely influenced his conceptions of the Queen of the Night. His mother-in-law, Cäcilia Cordula Stamm, was often harshly critical and angry with his wife. Mozart wrote of his second visit with Cäcilia that she chastised and angrily argued with his wife until his wife was brought to tears, leading to a resolution that they only visit her on family holidays.[6] The depiction of the mother-in-law as a battle-axe, who inspires Mozart’s Queen of the Night is shown in Peter Schaffer’s very loosely biographical play “Amadeus.”[7] Schaffer, probably overly vilifying her, has Cäcilia fly into a rage, berating Mozart for being “selfish” and mistreating her daughter in a scene that morphs into the Queen’s raging Second Act aria, “Der Hölle Rache.”

4. The Oboe and Opera

§4. As I have discussed in previous writings,[8] the oboe, the modern descendent of the muse Euterpe’s aulos, has been used in opera to convey femininity, epitomized in its use by Verdi in the aria “O Patria Mia,” in which the exiled and melancholy Aida sings of her fate of never seeing her homeland again. Like “O Zittre Nicht,” typically the Aida aria is sung with moon and night imagery in the scene, the moon being another symbol associated with the feminine.

The oboe’s unique timbre evokes all at the same time melancholy, a snake charmer-like seduction, and an air of mystery and magic and intrigue, all associated with classical conceptions of women.

§5. “O Zittre Nicht” and “Der Hölle Rache” are both scored for oboe, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello, and bass, while “Der Hölle Rache” adds flute and trumpet.[9] When one looks at the signature arias of the strong male characters, Tamino’s “Dies Bildnis is Bezaubernd Schön” is scored for clarinets, bassoon, horn, violins, viola, cello, and bass while Sarastro’s “In Diesen Heil’gen Hallen” is scored for flute, bassoon, horn, violin viola, cello, and bass, both excluding oboe. It is not simply a matter of the higher voice range of a woman needing the oboe as a high-pitched accompanying instrument. In the Queen’s soprano arias, the top treble woodwind is the oboe, but it is replaced in the tenor Tamino’s aria with flute, an even higher pitched instrument, and in the bass Sarastro’s aria, the clarinets, only slightly lower pitched than the oboe. It is not the pitch, but the unique timbre of the oboe that aligns it with the feminine. Interestingly, the signature aria of the male character Papageno, a birdlike man who catches birds, is scored for oboe as well. Although it is a lower voiced, baritone role, the character is somewhat gender-blurred. Dressed like a bird, another female symbol, he is constantly “zittering,” that is trembling in fear of the Queen and her maids and the trials of the temple, weak-willed, and deceptive in telling Tamino that he saved him from the beasts, all attributes classical Greeks like Aristotle associated with women.

5. First Act Aria: “O Zittre Nicht, Mein Lieber Sohn”

§6. The Queen we see in her First Act aria is the loving and grieving mother (and future mother-in-law).[10] Its title and opening lines “O Zittre Nicht, Mein Lieber Sohn,” say it all—“Do not tremble, my dear son.” These words from the librettist, Schikaneder, comfort Tamino, and by referring him to as “Mein Lieber Sohn” show the Queen to be a loving mother.

KÖNIGIN

O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn!

Du bist unschuldig, weise, fromm;

Ein Jüngling, so wie du, vermag am besten,

Dies tief betrübte Mutterherz zu trösten.

Zum Leiden bin ich auserkohren;

Denn meine Tochter fehlet mir,

Durch sie ging all mein Glück verloren –

Ein Bösewicht entfloh mit ihr.

Noch seh’ ich ihr Zittern

Mit bangem Erschüttern,

Ihr ängstliches Beben

Ihr schüchternes Leben.

Ich musste sie mir rauben sehen,

Ach helft! war alles was sie sprach:

Allein vergebens war ihr Flehen,

Denn meine Hülfe war zu schwach.

Du wirst sie zu befreyen gehen,

Du wirst der Tochter Retter seyn.

Und werd ich dich als Sieger sehen,

So sey sie dann auf ewig dein.

She laments her grief or ahkos from the loss of her daughter as well as her weakness and inability to save her daughter from the “evil” Sarastro’s abduction of her: “Denn meine Hülfe war zu schwach.” This grief of “losing” her daughter is reminiscent of the emotion felt in Thetis’s lament for Achilles in Iliad 18. While he is not yet dead, as the best of all warriors, Achilles is fated to die, and Thetis is helpless to save him. Moreover, Thetis laments for the grief her son feels that she cannot save him from, fitting as Achilles’s name comes from akhos or ‘grief’.[11] At the same time she encourages the brave and strong male character, Tamino, to be her daughter’s champion. The daughter, similarly weak, could only call for help, “Ach helft! war alles was sie sprach.” Only a man can “dies tief betrübte Mutterherz zu trösten,” comfort a sad mother’s heart.

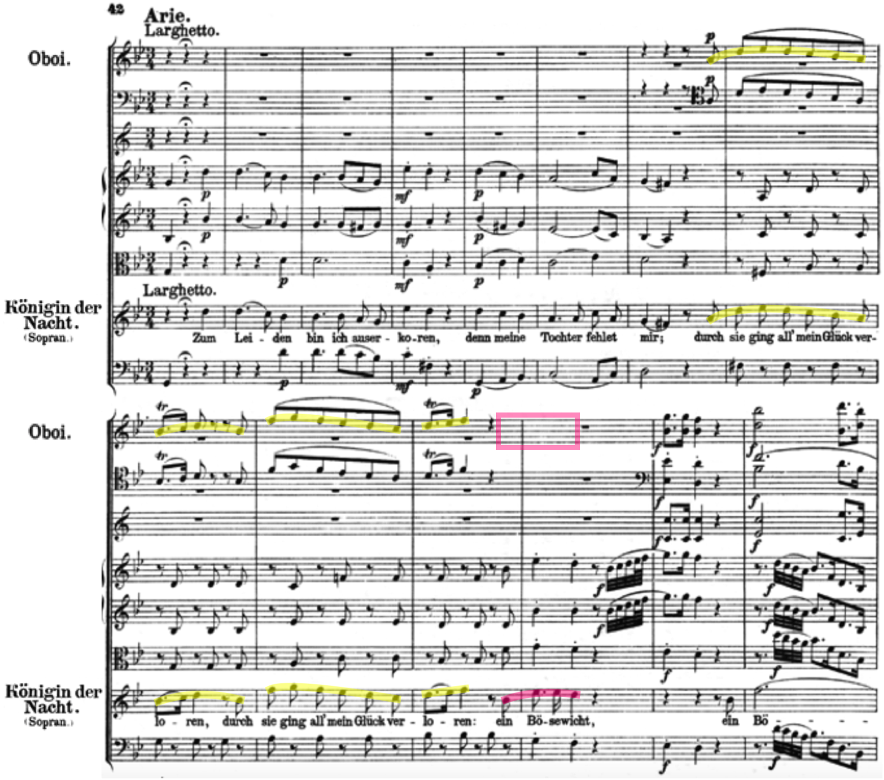

§7. Beyond the librettist’s lyrics, Mozart’s music emphasizes the concepts of femininity beginning with the melody and orchestration of the aria. In the recitative opening, the verse “O zittre nicht mein lieber Sohn!” is sung to a melody that contains a gradual ascent and a steeper drop, followed by another ascent and descent. This is echoed by the oboe (top line) and bassoon (second line) playing a melody that also rises and has a steep drop.

As the piece evolves into an aria, the melody of the repeated verse “Durch sie ging all mein Glück verloren,” is paralleled closely by the oboe, evoking the plaintive sentiment of the mother who has lost all happiness because she misses her daughter. This is typical of the use of oboe in opera, depicting melancholic women, as in “O Patria Mia.” However, when we subsequently see a brief glimpse of her anger in the words “Ein Bösewicht” (referring to the evil one who made off with her daughter), the melancholy oboe suddenly drops out (see the pink box in the image below)—the music jumps to forte dynamics briefly then returns to piano. It is a window into the vengeful, vindictive aspect of women which will be shown more clearly in her later aria. The sudden change also typifies the capricious and rapid changes in emotion associated with women.

A lovely performance of the First Act Aria by Diana Damrau can be heard here:

6. Second Act Aria: “Der Hölle Rache”

§8. The loving mother devolves into the raging avenger in her signature aria of the Second Act. Rather than being overjoyed at reuniting with her daughter, whose absence had robbed her of all happiness in the First Act, she is incandescent with rage and forces a knife into her daughter’s hand swearing to disown her if she fails to kill Sarastro. In the ancient language of the humors she has swung from melaina kholḗ, or ‘black bile’, in the First Act aria to kholḗ/kholos ‘yellow bile/hatred’ in the Second Act aria.[12]

Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen,

Tod und Verzweiflung flammet um mich her!

Fühlt nicht durch dich Sarastro Todesschmerzen,

So bist du meine Tochter nimmermehr.

Verstossen sey auf ewig und verlassen,

Zertrümmert alle Bande der Natur,

Wenn nicht durch dich Sarastro wird erblassen!

Hört Rache, —Götter!— Hört der Mutter Schwur.[13]

The fires or revenge of Hell are burning in her heart and the music echoes this. To me, the flames or “Tod und Verzweiflung flammet um mich” that surround her are evoked by the repeated eighth notes in the strings. The daughter, whom earlier she could not live happily without, is to be disowned if she fails to kill Sarastro: “So bist du meine Tochter nimmermehr.” Anger and Rache, or ‘revenge’, govern her heart. The violent swings of her emotion are evoked by the soprano’s repeated vocalized high C’s dramatically rising and falling in the following rollercoaster arpeggios and even hitting a high F (F6). In contrast to “O Zittre Nicht,” the melody is disjunct rather than conjunct, moving in larger intervals than whole and half steps. The pitch range actually spans two octaves from F4 to F6, again speaking to the wide swings of emotion.

Diana Damrau can again be heard, with the Royal Opera Covent Garden, in this video:

§9. In listening to “Der Hölle Rache,” it is not hard to imagine the vengeful Hērā’s plotting against Zeus’s various lovers and their resultant offspring. As the lyrics read, the Queen of the Night can only be appeased and accept her daughter back if the daughter slays Sarastro. Just as the cure for Hērā’s anger is the death of Hēraklēs, and would have been to “devour the uncooked flesh of Priam and all the Trojans,” as a depiction of Zeus noted, the cure for the Queen of the Night’s rage would be the death of Sarastro.[14] Contrast this with Sarastro’s signature aria which immediately follows “Der Hölle Rache.” The model of even-keel, Sarastro’s aria sings of forgiveness and brotherhood, rather than revenge. In lyrics and music, it is the inverse of “Der Hölle Rache.” The words begin “In diesen heil’gen Hallen, Kennt man die Rache nicht,” meaning “in these holy halls, man cannot know revenge.” The halls are filled with men and not women, like the Freemason temples, as only men can achieve real virtue and enlightenment, assuming they are not led astray by women. Sarastro’s aria is composed in an extremely conjunct melody with almost all notes rising and falling in half or whole steps, evoking an emotional calm and stability, as does the incredibly low pitch of the voice and the larghetto tempo.

7. Conclusion

§10. Lyrics and music coalesce in The Magic Flute to create a Queen of the Night who is the antithesis of enlightenment, stability, forgiveness, and brotherhood, hearkening back to Athenian concepts of femininity. As her two wildly contrasting arias convey, the Queen, like Hērā, captures the feminine duality of the loving mother and the emotionally labile raging avenger, surrounded by literal and metaphorical darkness. Yet, as Nagy has written, her “emotion is both terrifying and at the same time beautiful.”[15]

Bibliography

Jahn, O. 1882. Life of Mozart. 3 vols. Trans. P. D. Townsend. London. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/43412/43412-h/43412-h.htm.

Landzberg, R. 2018a. “The Oboe and the Different Faces of Femininity in Opera.” Unpublished paper for COMPLIT152: “Poetry and Opera,” Harvard University.

Landzberg, R. 2018b. “Euterpe’s Aulos in the Lyric Poetry of Ancient Greece.” Unpublished paper for CLASPHIL248: “Greek Lyric Poetry,” Harvard University.

Miller, F. 2017. “Aristotle’s Political Theory.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2017 Edition, ed. E. N. Zalta. Stanford, CA. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-politics/.

Mozart, W. A. 1985. The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte) In Full Score. New York. https://ks.imslp.net/files/imglnks/usimg/5/5b/IMSLP472368-PMLP20137-Mozart_-_Il_Flauto_Magico_(Partitura)_-_Edizione_Dover.pdf.

Nagy, G. 2015.10.29. “‘The Mother, so Sad It Is, of the Very Best’: The Lament of Thetis in Iliad 18.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-mother-so-sad-it-is-of-the-very-best-the-lament-of-thetis-in-iliad-18/.

Nagy, G. 2020.04.03. “Comments on Comparative Mythology 7, Finding a Cure for the Anger of Hērā.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/comments-on-comparative-mythology-7-finding-a-cure-for-the-anger-of-hera/.

Shaffer, P. n.d. Amadeus. Daily Script. http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/amadeus.html.

Smith, N. D. 1983. “Plato and Aristotle on the Nature of Women.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 21(4):467–478. https://doi.org/10.1353/hph.1983.0090.

[1] This essay was written for the seminar COMPLIT 156: “Performance and Lyric” with Gregory Nagy in Spring 2020.

[2] Smith 1983:468.

[3] Miller 2017.

[4] Mozart 1985:98.

[5] Mozart 1985:1.

[6] Jahn 1882, 2:324.

[7] Shaffer n.d.

[8] Landzberg 2018a and 2018b.

[9] Mozart 1985:41, 133.

[10] Mozart 1985:41–45.

[11] Nagy 2015.10.29.

[12] Nagy 2020.04.03.

[13] Mozart 1985:133–138.

[14] Nagy 2020.04.03 §8.

[15] Nagy 2020.04.03.