2020.12.11 | By Gregory Nagy

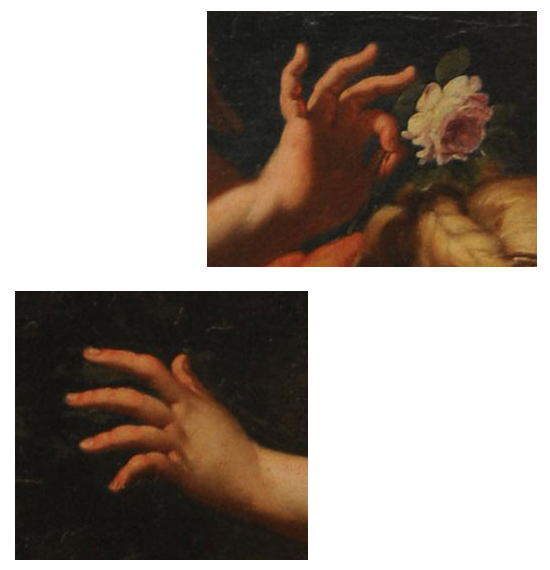

§0. In the “Tithonos Song” of Sappho, the fragmented text of which has of late been supplemented with newly-found additional papyrus fragments (text here), we read how the amorous goddess of the dawn, Eos, abducted the beautiful hero Tithonos to be her youthful lover—but she was unable to prevent him from slowly turning into an old man, deprived of his youth and beauty. This sad story is retold in the Tithonos Song, where the female speaker who is retelling the story, now an old woman, has just now called out mournfully to young girls with whom she used to sing and dance, declaring to them that her poor old knees are not up to it anymore: she is no longer able to dance. In what follows, I will argue that the loss of an old woman’s power to dance is being contrasted in this song of Sappho with the ever-youthful and ever-beautiful dancing power of the dawn goddess Eos. And that power of dance, I will also argue, is divinely fueled by the rose-colored female energy of the dawn’s early light. The entire body of the dawn goddess is activated by that power, so that all parts of this divine organism become engaged in her dance. All parts are in motion: her feet, her hands, all the rest of her—even the tips of her fingers. In the introductory illustration for my essay here, I show an extreme-zoom close-up of a not-so-ancient (seventeenth-century) painter’s highlighting of the delicately dancing fingers of the dawn goddess Eos, known in Latin as Aurora. The ancient epithet of this goddess in Homeric poetry, rhododaktulos (rhododactylos), is most fitting: the divine Eos is ‘rosy-fingered’ Dawn.

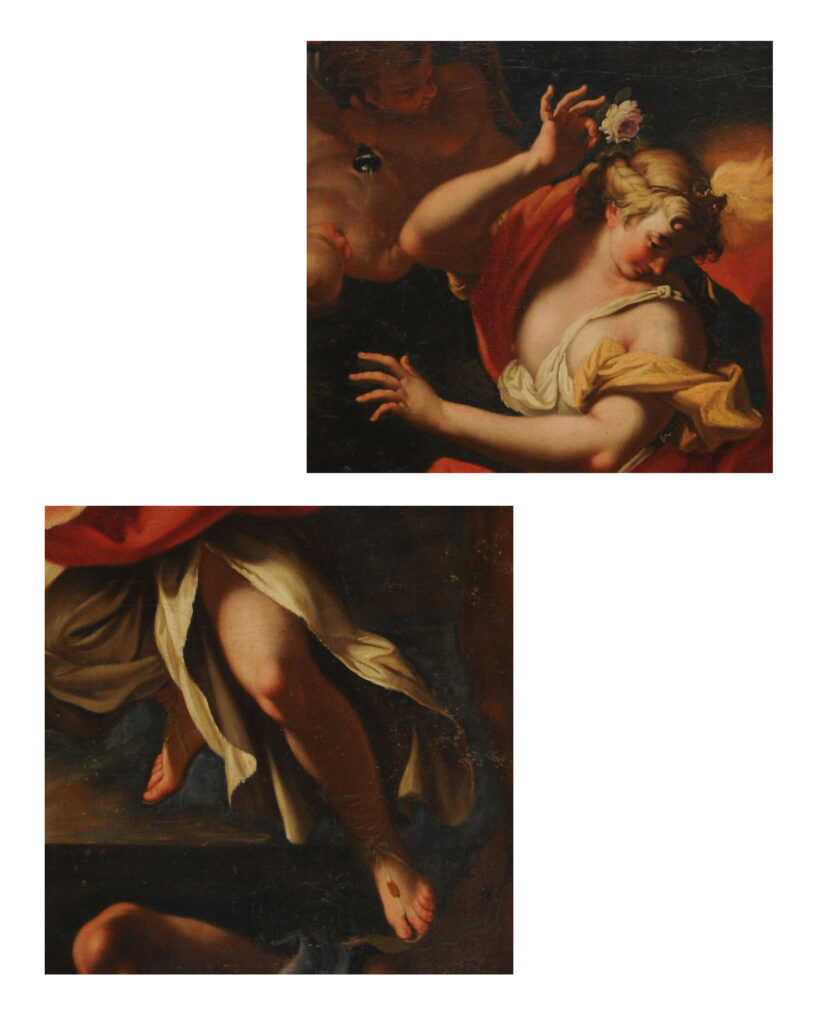

§1. What I next show, immediately above, are (1) a mid-zoom close-up of Aurora viewed (1a) above the waist and (1b) below the waist, followed by (2) a zoom-out full view of the picture painted by our painter. As we can see, the complexion of Aurora is rosy from head to toe, and the painter has highlighted her rosy complexion by showing her delicately pink fingers on the verge of touching a delicately pink rose. This rose mediates the rose-coloring of the rising sun that attends the dawn goddess as she gracefully rises up from the darkness below the horizon. Left behind in the dark is the sad old man Tithonos (the Spanish spelling for him here is Thyton). Our painting has faithfully captured the Homeric moment, described in both the Iliad (11.1–2) and the Odyssey (5.1-2), when Eos rises at dawn, leaving the bed she shared all night with Tithonos.

§2. Our painting shows Eos striking the pose of a dancer. But how do we know that Eos was a dancer in ancient Greek traditions? There is direct evidence in Homeric poetry. In Odyssey 12.1–4, we read that Eos the goddess of the dawn has her own palace in the Far East, where the sun rises, and she has a special space there for her choral ‘singing-and-dancing’, that is, for her khoroi (Nagy 2017 at O.12.003–004). And it is relevant, as I pointed out in my Greek Mythology and Poetics (Nagy 1990:150), that a cognate goddess of the dawn, Indic Uṣas, is invoked as sūnr̥tāvatī ‘good at dancing’ (Rig-Veda 4.52.4).

§3. But can we really think of the rosy fingers of Eos, goddess of the dawn, as fingers that dance? I have no doubt, having surveyed cross-culturally a wide variety of dance traditions. In dance, the graceful movements of fingers connect to hands connect to lower arms connect to upper arms and so on (… connect to shoulders connect to neck connect to head connect to mouth connect to eyes). So, I have no doubt that the fingers of Eos the dawn goddess are dancing fingers. And my thinking here is confirmed by the language of Sappho: at line 9 of the Tithonos Song (text here), the dawn goddess Eos, whose name is pronounced Auōs in the Aeolic dialect, is described as ‘rosy-armed’ (βροδόπαχυν Αὔων). The Aeolic form brodopākhu-, which is rhodopēkhu– in the Ionic dialect and which I translate for the moment as ‘rosy-armed’, is built with a noun pēkhu– that means, literally, ‘elbow’. And, in terms of my understanding of metonymy as an expression of meaning by way of connecting, there is a metonymic force at work here, since the elbow is the joint that connects the upper arm to the lower arm, and, if we focus for the moment on the lower arm, the noun pēkhu– is actually attested as referring to the lower arm, extending from the elbow all the way down to the tip of the middle finger (Pollux 2.58). Thus, the rosy arms of the dawn goddess—both the upper arm and the lower arm that extends all the way down to the fingertips—are all activated in the bodily connectivity of motion in dance.

§4. Just as the elbow is a joint that connects the upper arm to the lower arm, so that the rosiness of the dawn goddess extends downward from her elbow, down to her lower arm and then all the way further down to her fingertips—while the rosiness also extends upward to the upper arm and further up from there—the same kind of thing can be said about the knee as a joint that connects the upper leg to the lower leg, which in turn extends further down to the ankles and then to the foot and then all the way down to the toes of the foot. So, if the poor old knees of the old woman in the Tithonos Song are not up to dancing (text here), then there can be no further fancy footwork poised on nimble toes.

§5. The epithet of Dawn, rhodo-daktulos ‘rosy-fingered’, can actually mean also ‘rosy-toed’, as I pointed out in Greek Mythology and Poetics (1990:247), since the -daktulos (-dactylos) of rhodo-daktulos can mean ‘toe’ as well as ‘finger’. There are numerous attestations in ancient Greek where the noun daktuloi refers to toes, not fingers (for example, Xenophon Anabasis 4.5.12). Thus the picture we have been viewing is faithful to yet another aspect of the dancing Eos, since the painter displays most sensually the rosy toes of the goddess, accentuated by her rose-colored sandals—and even her rosy knees.

§6. In the poetry of John Milton, it seems that the Dawn, personified as Morn, can actually be pictured as both rosy-toed and rosy-fingered. With the guidance of my genial colleague Gordon Teskey, I cite two passages from Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). At 5.1–2, we read:

“Now Morn her rosy steps in th’eastern clime | Advancing sowed the earth with orient pearl.”

Then, at 6.3, Morn is pictured as “waked by the circling Hours,” unbarring the gates of light “with rosy hand.”

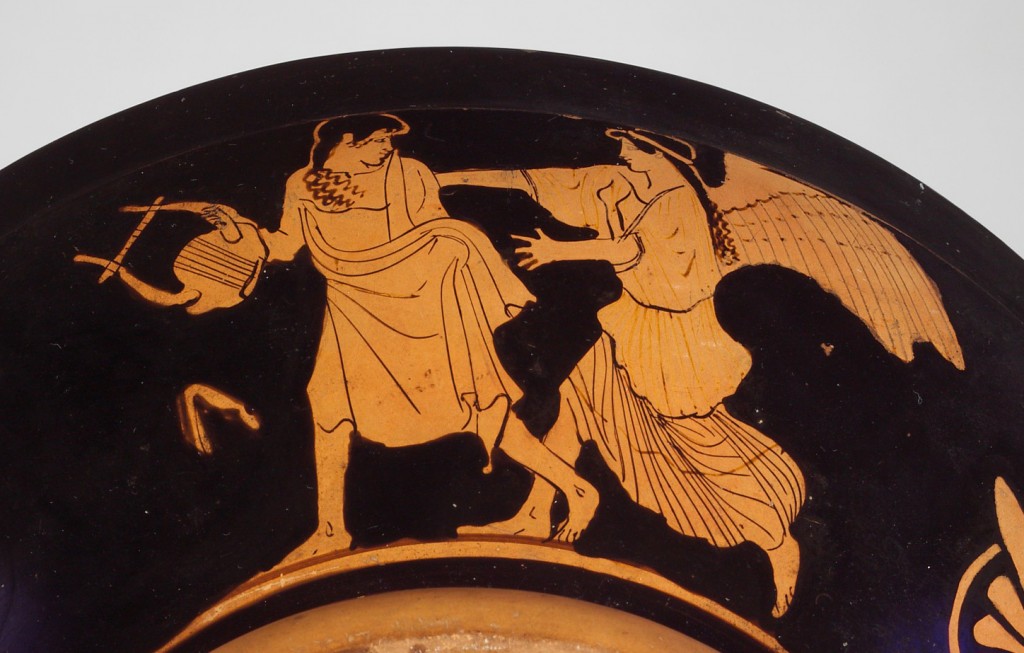

§7. It almost goes without saying that the rosy beauty of the dawn goddess, timelessly admired by poets and painters, is matched by her sensuality. In an essay to come, I will have more to say about the traditional connectivity of roses with sensuality, especially as embodied in the goddess Aphrodite, but for now I remain focused on Eos, who is in her own right a mythological prototype of Aphrodite, goddess of sexuality and love, as I showed in Greek Mythology and Poetics (Nagy 1990 chapter 9; also Nagy 2015.11.12). In a classical Athenian vase painting, Eos is actually pictured as a female Eros, with fluttering wings extending from her beautiful shoulders. In this painting, which I show here, we see Eos chasing after a youthful Tithonos. He is pictured as a singer, holding on to his lyre as he fearfully tries to run away from the pursuing goddess. The lyre signals, I think, the picturing of a musical pas de deux that is danced by the pretty boy and the sensual goddess who pursues him.

§8. Such a scene, as sensual as it is also beautiful, evokes for me the poses of Sappho as a look-alike of goddesses, especially of Aphrodite. And, as I have shown in previous essays, listed in the Bibliography, such poses are dancing poses. So, I see a special sadness in the declaration of the old woman in the Tithonos Song of Sappho (text here): my knees have given out, and I cannot dance any more.

§9. I have learned much about the ancient reception of Sappho by viewing, time and again, painterly visions of female beauty in classical Athenian vase paintings—especially in pictures attributed to the so-called Meidias Painter, who lived in the fifth-century BCE. Although the references to Sappho and to Sappho’s songs in the visual art of these paintings are more often indirect than direct, they have much to tell us about the verbal art of Sappho and of other preclassical masters of song—and I include here that ultimate Poet, as Plato thinks of him, Homer himself. Such verbal art, I must point out, is a form of visual art in its own right, since it is integrated with the human body in the form of dance, which is an integral part of song in preclassical and even classical Greek verbal art.

§10. In this essay, then, I have viewed song-and-dance as an integrated visual art that can be compared directly to the visual art of painting. That is why I referred metaphorically, already in the title of my essay, to the verbal art of Sappho and beyond as a painterly art. In terms of this metaphor, then, it becomes easier to see how such a painterly art of song-and-dance is most readily visualized in real paintings that represent real dance directly—and real song indirectly. And it becomes even easier to see how the art of the painter, in ancient times and ever since then, can bring to life such a reality.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.