2020.11.20 | By Gregory Nagy

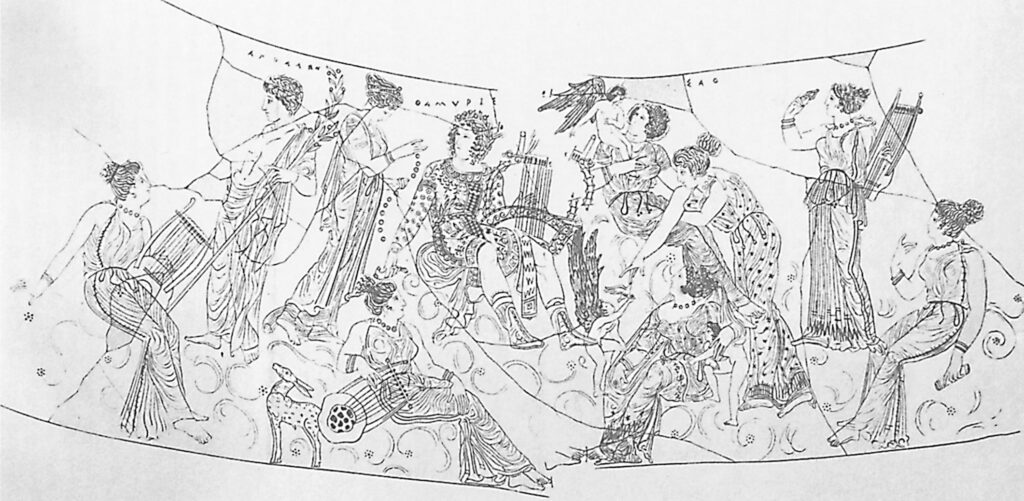

§0. For a picture that illustrates one of my many desiderata as I go about tracing the ancient reception of Sappho, I have chosen a line-drawing that shows a close-up from a vase painting. The painting, if we were to view it in its entirety, centers on the youthful male beauty Adonis. In the moment that is captured by the painter, Adonis is being kissed by a personified Eros, a cupid. Meanwhile, framing the figure of Adonis on both sides are two female beauties—or I could just as readily say two girls—whose names, indicated by lettering placed next to their beautiful figures, are likewise personifications—the girl to our left is Eunomia and the girl to our right is Eukleia. In the close-up, we see Eukleia, personified as ‘she who has genuine kleos’—where kleos means ‘glory of song’. The girl is holding a lyre in her left hand, and she is fingering the strings of her lyre while a little bird is perched on the index finger of her right hand. In the light of related essays of mine that I have listed in the Bibliography below, a girl like Eukleia could be imagined, I would like to think, as Sappho herself.

§1. But how could I say more formally here what I have just said—that I would like to think of Eukleia as Sappho herself? I could say that this girl personifies a fleeting memory of an image that our painter had in mind by remembering—maybe only vaguely—how he once had heard a performer sing a song by Sappho that pictured such an idealized girl. Or, to put it a better way, I could say that not only our painter but many other painters painted their own reminiscences of girls—not one but many girls—as idealized in songs by Sappho or by her imitators. My desideratum, in any case, would be to show that such a picturing of a girl in the visual art of a painting is reminiscent of girls pictured in the verbal art of Sappho. But such desiderata cannot be backed up by way of any single thread of argumentation. Rather, a whole web of arguments would be needed.

§2. Engaging now in such argumentation, I pick up the thread by asking another question: what seems to be missing in the overall painting that pictures the beautiful girl Eukleia, who is standing next to the loving pair of Adonis and Eros? What is missing, I argue, is Aphrodite, goddess of erotic desire. To say it somewhat playfully, the desideratum for reading the overall picture here is the missing personification of desire itself.

§3. But such a personification is not really missing in this picture, as it turns out. Aphrodite is not really absent, since Eros himself is present, and he is the male personification of erotic desire, the noun for which is eros. In this same picture, the male beauty who is Eros is seen in the act of kissing the male beauty Adonis. Further, such an Eros can also be personified as Himeros, a male beauty whose name personifies the noun himeros, which means ‘longing, desire’.

§4. The connectivity of Himeros with Aphrodite is evident. I cite as a blatant example a painting by the Meidias Painter, as I analyzed it at §5 in a related essay, Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here: in that painting, we see Adonis embraced from behind by Aphrodite, and hovering over the loving pair is a winged cupid, or Eros, named Himeros, who as I say is a personification of ‘longing, desire’. In another painting by the Meidias Painter, as I analyzed it at §2 in another related essay, Nagy 2020.11.13, linked here, Himeros together with Pothos, whose name likewise means ‘longing, desire’, are pictured as drawing a chariot driven by Aphrodite herself. In that painting, the focus of attention is not on Adonis but rather on another love-object of Aphrodite, the youthful male beauty named Phaon.

§5. In the case of the painting where the Meidias Painter highlights Phaon and not Adonis as the main object of erotic desire, this love-object is pictured as playing on a lyre, just as Eukleia in our painting of the moment is pictured as playing on her own lyre. I find such connectivities most telling. If we may define metonymy simply as an expression of meaning by way of making mental connections, which is the essence of what I argue in my book Masterpieces of Metonymy (2016|2015), then the connectivities that we see in these two paintings may be described as metonymic.

§6. And the metonymy extends further. We may compare the little bird that is perched on the index finger of the beautiful girl Eukleia in our painting of the moment with a detail we find in yet another painting created by the Meidias Painter—where another beautiful girl is extending her index finger to receive another little bird that is perched on the index finger of another Eros. In this painting by the Meidias Painter, the center of attention is occupied by yet another youthful male beauty, Thamyris, who is shown playing his own music on yet another lyre.

§7. As we consider once again the overall painting that features Eukleia with her lyre and with her little pet bird perched on her index finger, I may ask again, as if I had not already asked this question before: who is really missing in this picture, if not Aphrodite herself? My answer is: Sappho is missing. But then again, just as Aphrodite herself is not really missing, since many of her connectivities are made patently visible, so also Sappho herself, as a surrogate of the goddess, is not really missing, either. Rather, Sappho is simply being replaced by another surrogate of Aphrodite, who is Eukleia. This other surrogate is an invisible Sappho made visible again, like the Lesbia of Catullus, that poetic girl who teases her own little bird in Poem 2, only to mourn his death in Poem 3. Just like Aphrodite, Sappho too can be invisible and yet present, ever-present, embodied in the beauty of the girls in her songs.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.