2021.09.10 | By Gregory Crane[*]

Abstract: This paper consists of three complementary parts. The first section describes three instances where very technical scholarship on Greek literature overlaps with, and draws attention to, particularly dramatic historical contexts. This section describes an aspect of Greco-Roman studies that is both too demanding and too narrow — too demanding because it assumes that anglophone researchers work with scholarship in languages such as French, German, and Italian, but too narrow because it does not engage with scholarship that is not in a major European language. The second section talks about the general need for Classics and Classical Studies in a country such as the United States to extend beyond Greece and Rome. This section builds on work that I have published in the past distinguishing Greco-Roman from Classical Studies. The third section describes a more concerted attempt to expand beyond North Africa and to include sources from Sub-Saharan Africa. I report on developing for a spring 2021 course on Epic Poetry a 10,000-line Mandinka/English corpus of stories produced by West African Griots. I will also briefly discuss the use of Classical Arabic to explore locally produced sources about West African history and culture. As a first step, the fall 2021 course on Classical historians at Tufts University will center not only on sources such as Herodotus, Thucydides, Livy and Tacitus but on two histories that focus on the Songhay Empire: the Tarikh al-Fattâsh, begun c. 1593 by Mahmud Kati, and the Tarikh as-Sudân, composed by al-Sadi (c. 1594–1655). This class will expand the role of Classical Arabic in Classical Studies at Tufts.

The technical study of Greek literature and the echoes of a larger world

§1. The reception of Greek and Roman culture over time in society as a whole is, of course, a lively field of its own. But even the most narrowly academic research on Greek and Latin, published in traditional languages of Greco-Roman studies such as English, French, German and Italian, challenges us to imagine places and situations far removed from our own. One of the great pleasures of this field for me is, even when working with the output of other scholars, to find myself thrown unexpectedly into a very different time and place. The basic subject matter is the same and some topics have been explored for centuries. But even if we are pursuing what seem to be very technical scholarly topics, we can find ourselves suddenly transported out of the narrow world of scholarship and blinking in the light as we realize that we have entered not only into a fundamentally alien ancient world but also into modern worlds that are also arrestingly different from our own experience.

§2. Sometimes, the pointers to the historical context are explicit, if incomplete. I offer three examples, each of which I encountered as I worked in the near complete solitude of the library at the Center for Hellenic Studies[1] during the Pandemic. The first occurred when I was rereading the work of the 20th century American scholar Milman Parry.

§3. Parry himself had his own compelling story: born in Oakland, California, in 1902, he earned his BA and MA at Berkeley, one city over. He continued his graduate career in Paris, where he mastered French and then composed his dissertation(s) on the Traditional Epithet in Homer.[2] The technical language of the title belies the breadth of its impact: in his Paris dissertations, Parry elaborated upon an insight that he had already developed in his Berkeley MA thesis: Homeric poetry was designed for rapid production by oral poets who composed their performances on the fly. Such formulaic composition reflected the demands of a poetic tradition that had evolved over centuries through oral transmission and differed in demonstrable ways from subsequent epics produced in a tradition of written text. In Paris, Parry met the Slovenian scholar Matija Murko who had worked with, and even recorded, compositions from a then living oral tradition in the new nation of Yugoslavia. In 1933 and 1935, Parry made his way to Yugoslavia to meet and record these poets. Parry died prematurely in 1935, but his assistant Albert Lord demonstrated how closely the mechanics of the South Slavic tradition aligned with those of Homeric poetry. Parry upended assumptions behind a century of professional scholarship, much of it German, that had assumed that the Homeric epics were too extensive and complex to have been the direct products of an oral tradition and who did not understand how oral composition could account for the frequent repetitions and general formulaic nature of the Homeric Epics. As an undergraduate and graduate student, Parry had always been a promethean figure for me. I attended the final lectures that Parry’s student and collaborator Albert Lord delivered and heard Lord play recordings of South Slavic poetry in a 1980 seminar on Homer. Pictures of the former professors of Classics lined the walls of the Smyth Classics Library in Widener. All were men. All had grey hair—all except Parry, whose still youthful face gazed out more directly, I thought, than any of the others. The portrait was a bit out of focus in comparison with the others—it was a detail blown up from a larger scale picture. At his death at 33, he was barely half his way to 65 and most of his professional career should have lain before him.

§4. But Parry’s work called into question assumptions behind more than a century of most German scholarship on the origin of the Homeric epics, Parry also built on German scholarship in general and particularly cited the work of the nineteenth century German scholar Heinrich Düntzer on “evaluating conventional epithets in Homer” (zur Beurtheilung der stehenden homerischen Beiwörter). Homeric epithets (a fancy word for adjectives, largely, but not exclusively, applied to people and places) can broadly be divided into two classes. Some epithets only characterize particular figures: the epithets polymêtis (“a person of many tricks”) and polutropos (“a person of many manners”) only apply to Odysseus in Homeric epics (4 and 2 times respectively). An epithet such as dios (conventionally rendered “godlike”) appears more than 400 times and applies not only to Odysseus (103x) but also to Achilles (57x) and Hector (37x). Most strikingly, the next most common figure described as dios is Eumaeus, the “swineherd” of Odysseus. The epithet dios is thus treated as a conventional epithet that tells us little about the particular character.

§5. Düntzer talks about conventional epithets such as kalos, aglaos, agauos, and faidimos and how each is used to describe people and objects in the Homeric epic in one positive way or another. Each of these epithets arguably has little meaning other than to confer a far-off glamor to the epic world. He talks about how we can assess these epithets and distinguish them from more precisely meaningful words. The essay was more than fifty years old when Parry cited it in the 1920s. Almost a century after Parry and hundred and fifty years after its publication, I found its discussion of Homeric language still well worth reading.

§6. But aside from its considerable technical interest, the remarkable thing about this paper is that it only gets to the Homeric epithets on page three of a ten-page article. The article opens with the following proud statement:

“If nature distributed dispositions and inclinations in the wisest mixture among the various peoples, she did not give any of them the penetrating sense to put themselves into foreign characteristics, to absorb foreign ways, foreign approaches, feelings and thoughts and to let them resound in the same measure as she gave it to the Germans, whom she thereby determined to be the people in whom philology in the broadest and noblest sense of the word should develop to its richest flowering.”[3]

§7. Of course, the boast is an assertion of German nationalism but, paradoxically—and, to me, poignantly—the source of that nationalistic pride is the very imaginative sympathy that Düntzer claims for German scholars. Germans are, he argues, the finest philologists because they are the most open to the thoughts of those who are not like them. This view of German nationalism is based on a claim to transcultural, cosmopolitan sensibility. If nationalist competition could have consisted of a competition in intellectual generosity, history would have been very different.

§8. Düntzer goes on to trace a genealogy of German philology, starting with general intellectuals such as Johan Joachim Winkelmann (1717–1768), Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), Christian Gottlob Heyne (1729–1812), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and climaxing with Friedrich August Wolf (1759–1824). Wolf’s 1795 Prolegomena ad Homerum (“Introduction to Homer”)[4] established the question of how our Homeric epics took their current form as a leading research question in Germany throughout the nineteenth century and beyond. Their connection to Greek culture, Düntzer tells us, had allowed Winkelmann, Lessing, Herder, Heyne, and Goethe “had expanded their soul” (sich die Seele ausgeweitet hatten). The introduction concludes by linking the study of Homer and of Classical Philology (i.e., the study of Greco-Roman culture through its textual record) to the rise of the German nation:

“Since that time, the Homeric question has become a German one; Germans, for the most part, have tested their acumen on this most important point of classical philology, and if even now the views on this great scientific, as well as on the political, German question are still sharply and decisively opposed, new points of view have been gained in the struggle itself, and we may live in the joyful hope that one day, in a united Germany, German research (Wissenschaft), too, will determine its own final verdict on it.”[5]

This burst of national pride is a long way from the technical discussion of when epithets are generic or more particularly meaningful in Homeric Greek.

§9. This essay appears in a collection of his publications on Homer that was published in 1872. The paper originally appeared in “the transactions of the twenty-first philological convention” and no date for this event is offered, but the preceding publication appeared in 1865 and the following in 1868, so this paper presumably appeared between 1865 and 1868—shortly after the guns had stopped firing in the American Civil War and France and Prussia were moving towards their own conflict in 1870. The collection itself appeared the year after the first unification of Germany in 1871, an event that took place after Prussian victory over France helped consolidate a shared sense of German national identity that had been growing for generations. But, assuming the text above reprints what Düntzer published between 1865 and 1868, we encounter in the lead up to a very technical discussion some of that national ferment that led to the voluntary unification of Germany a few years later.[6]

§10. Come for the Homeric epithets—stay for the insight into European nationalist thinking in the 19th century! I would be surprised if more than a handful of Americans with college degrees knew much, if anything, about the unification of Germany in the 19th century. I wonder how many professional students of Greco-Roman culture know much about this story. Citations to German sources in English-language publications on Greece and Rome have collapsed since the middle of the twentieth century and I know only of a few colleagues who might find themselves ploughing through 19th century German scholarship on Homer. But those who do and who allow themselves enough time to pause and explore the context of what they are seeing in passages such as those quoted above will find themselves reflecting on topics of even greater impact than the Homeric question. Because the study of Greece and Rome was a transnational field within the European cultural sphere and because researchers on this topic are expected to read scholarship in multiple languages (typically English, French, German and Italian), even as we pursue very general questions where the terms of discourse are relatively generic (e.g., the evaluation of generic vs. specific epithets), we inevitably encounter moments where the historical and cultural context behind the publication jumps out at us, as in the case of Düntzer’s article.

§11. At other times, the scholarship does not explicitly draw attention to historical contexts that, if we pause and reflect, stop us in our scholarly tracks and challenge our imaginations to call those contexts to life. I offer two further such examples, which I also encountered while working at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

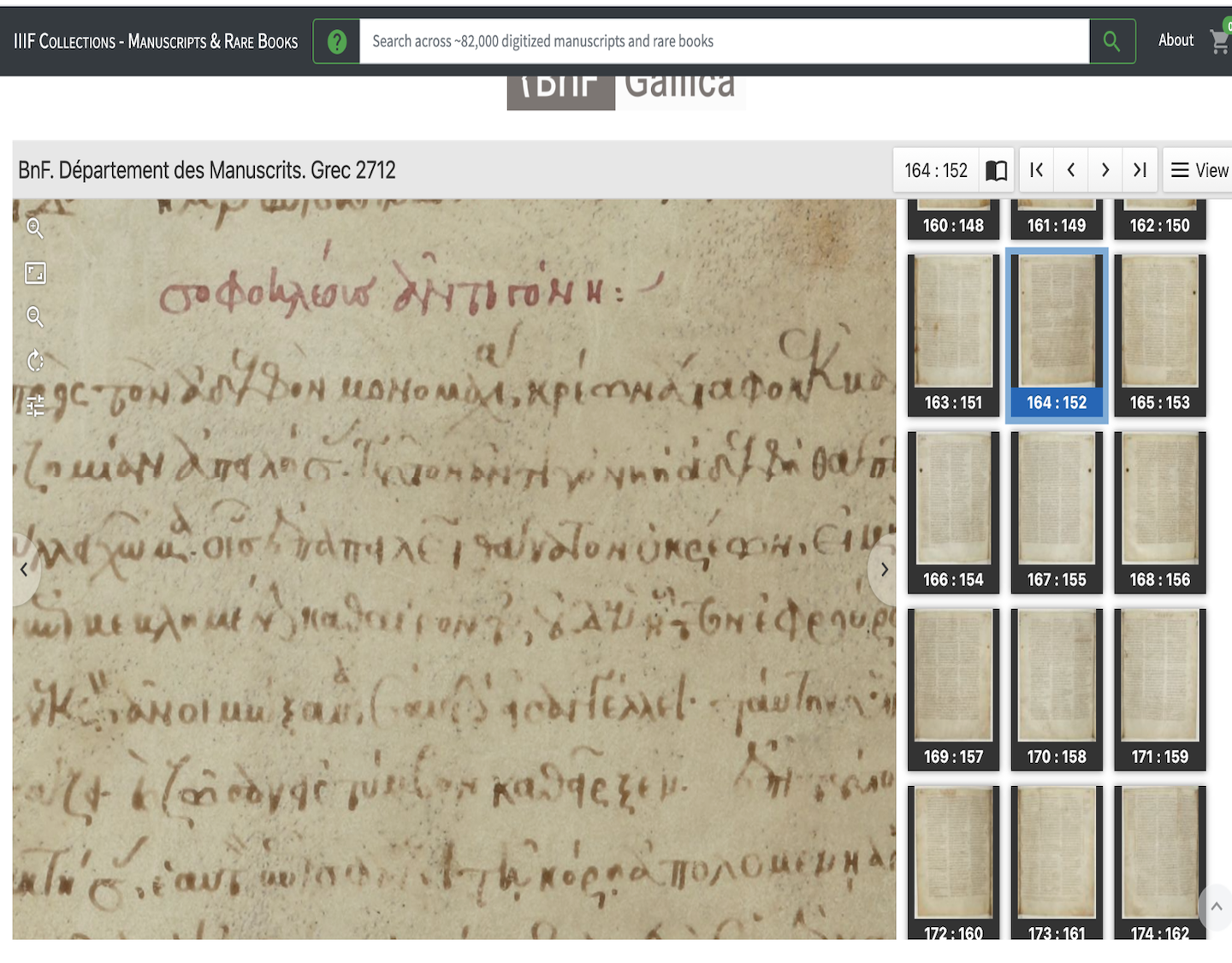

§12. I spent some of my time at the Center for Hellenic Studies studying the history of the Greek text of Sophocles and focused on particular on editions of the Antigone, from Friedrich Heinrich Bothe’s 1806 Berlin edition to the 1999 edition that Mark Griffith prepared for his Cambridge Commentary.[7] Overall, I have created digital transcriptions for 14 editions. Of these, I published on GitHub the curated TEI XML for the 11 editions that are in the public domain.[8] I wanted to see how much variation occurred across these editions over time, to explore ways of aligning them to each other so that I could publish a kind of variorum, and to classify, insofar as possible, the types of variation so that readers could identify the variants and editorial choices of most interest to them.[9] We need to move past the current model of providing access to a single, favored version of each historical source, and Sophocles’ Antigone provided me with a starting point to explore the problems and possibilities.

§13. To learn more about the textual history of Sophocles, I was laboring through the Latin introduction to Pearson’s 1924 edition of Sophocles and came across what I had previously passed quickly over as a generic credit to a collaborator. The note thanked a certain Walter Heathcote Lock for checking nearly 300 readings in the manuscript that Pearson labelled Manuscript A: a thirteenth century manuscript in Paris.[10] In 2021, direct observation of the manuscript will still be needed for some tasks, but I could do a great deal remotely. I can now call up high resolution images of this manuscript via the new International Image Interoperability Format (IIIF: https://iiif.io/).

In 1919, print facsimiles of important manuscripts had begun to circulate but they could not provide the detail available now from high resolution scans. A visual check was even more important than today.

§14. Before I kept slogging ahead through the Latin introduction, a couple of details awakened my attention and made me pause for a closer look. First, Pearson described Lock as a scholaris at Corpus Christi—an undergraduate. And he was not only an undergraduate, but one who had been deputized to examine almost 300 passages in a medieval manuscript. Parsing out such sources, with their idiosyncratic scripts and multiple hands, is a task that I have seen contemporary editors treat as demanding and requiring experience in paleography. I had not seen such responsibility handed over to an undergraduate who had to work independently—there was, of course, no way for Pearson to comment on pictures that a 21st century student might have sent back with his smartphone and almost surely no way for Pearson to talk to Lock on the phone as Lock worked. Comparably, The Homer Multitext Project relied upon c. 200 undergraduate contributors to create the first full diplomatic edition of the Venetus A, a tenth century manuscript containing not only the text of the Iliad but also a wide range of ancient annotations on different topics (scholia). I had written about the significance of this project precisely because it engaged undergraduates as serious collaborators on a demanding task.

§15. Pearson also stated, without comment, that Lock did this work during 1919. I quickly discovered a genealogy of the Lock family and found that Lock had been born on December 5, 1900.[12] Thus, Lock very probably was scanning 300 passages in the Paris manuscript while he was still 18. More generally, I realized that Lock had been just young enough to escape being fed to the meat-grinder on the Western Front. Paris itself was still recovering from the war but the great influenza was in full force: Woodrow Wilson showed his first symptoms of the flu on April 3, 1919, when he was at the Paris Peace Conference. Lock was doing extensive and irreplaceable work at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in a war-scarred Paris during the global pandemic of his age. Why was he there? Where did he stay? What else did he do during his trip? What did he see as he walked those streets, had dinner, or lived his life? I had no answers, but my imagination caught fire as I imagined the circumstances of this young man’s work.

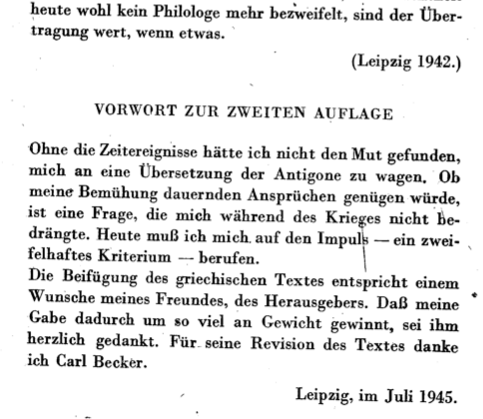

§16. In my Sophocles work, I was particularly interested in editions that had accompanying translations because I wanted to study the degree to which editors expressed their editorial decisions in their translations. In the simplest case, it would be helpful for many readers to know which editorial decisions did and did not have an impact upon the translation. On the shelves of the Center for Hellenic Studies library, I came across the second edition of Karl Reinhardt’s translation of the Antigone. This contained a facing Greek text revised by Carl Becker that the publisher apparently added so that the translation would “have that much more weight.”

§17. I was uncertain as to whether I would include this text and translation—in particular, Reinhardt lived until 1958 and his work will not pass into the public domain until 2028. For now, I could not create a Creative Commons licensed version of this translation and finding the rights holder seemed daunting. The Center for Hellenic Studies had the second edition, which was published in 1949, on bad paper that had already grown yellow and brittle and that thus physically evoked the stressed conditions of postwar Germany. Reinhardt signed the preface to the first edition “Leipzig 1942,” and I made a mental note to see how Reinhardt had presented this play, with its opposition of family to state, under the Nazi regime during the war. I also noted that, in the second edition, Reinhardt had said that, while the war raged, he had not worried too much about the long-term impact of this work. My mind turned to Leipzig in the war—to the fire bombings that the British directed against its print industry and that destroyed much else. Still, I did not need to create a machine-readable text from this book—a simple scan would be enough.

§18. I changed my mind and resolved to digitize this text and translation when I saw the location and date of the preface to the second edition. Where the preface to the first edition states simply “Leipzig 1942,” Reinhard was more precise in signing the second edition: “Leipzig, im Juli 1945,” Leipzig in July of 1945.[13] When I saw the date, with its added precision, my stomach clenched, and I felt physically shaken. I knew very well what had happened in Leipzig in July of 1945—or, more properly, I knew very well that I did not know and could never fully imagine that city at the time. July 1945 was one of the darkest moments in the thousand-year history of Leipzig.

§19. Three major bombing sorties had targeted Leipzig on December 3, 1943, February 20, 1944, and February 24, 1945, with a number of lesser raids during the war—like many German cities, Leipzig was filled with smashed buildings and whole sections were largely desolate.[14] In April 1945, the 69th American infantry division had overcome substantial resistance and occupied the city—the final struggle took place against holdouts barricaded in the surreal monument to the 1813 battle of Leipzig just south of the main city. The Life magazine photographer Margaret Bourke-White took photographs of the mayor, his wife and daughter after they had taken their own lives in the city hall.[15]

§20. American occupation was short-lived: under the terms of the Yalta agreement, the US handed Leipzig over to the Red Army in the beginning of July. The occupation of Leipzig, like that of Berlin two months before, was brutal. I was Professor of Digital Humanities at Leipzig University from April 2013 through September 2019. I owned an apartment there and I loved the city. I can remember in 2013 how one bearded artist, a tour guide, who might have been born as early as the 1970s, who took my research team through part of the city suddenly veered off from his regular program to talk about what had happened when the Red Army occupied, his Saxon accent thickening as emotion took him. A historian of Germany reported to me that residents of the city created places for women to sleep under the floor because the Soviet troops could break in at any time and there was no redress. The New York Times opens Judith Matloff’s review of Christina Lamb’s book on sexual violence in warfare, Our bodies, their battlefields (London 2020) with a widely reproduced picture of two Soviet soldiers, laughing as they harass a German woman, her head bowed in shame, on the streets of Leipzig.[16] A Leipzig PhD student born in the late 70s told me that the shortest route to his grandmother’s house passed by the main Russian barracks—and they always took the long way. As I walked the streets of Leipzig and took the tram home, I felt myself that I could still see signs of the harsh occupation: the older inhabitants of the city who had been born after the war often seemed to me to be markedly smaller than their fellows, as if they had suffered malnutrition as children. More than half a century later, the 83-year-old Bowdoin Professor of Philosophy and Humanities Emeritus Edward Pols,[17] who had been a 26-year-old American soldier in 1945, published a poem entitled “Leaving Leipzig (Early July 1945)” in the Sewanee Review.[18] The American soldier, it appears, knew what would happen when they left and the memory apparently haunted Pols for the rest of his life.

§21. And there (reproduced below) are Reinhardt’s bylines for the two editions of his translation. The first simply “Leipzig 1942”—in a city not yet directly touched by war, a year before the British had set their sights on Leipzig and unleashed firestorms on the morning of December 3, 1943.

The simple and uncommented addition of the month to the second preface, not just 1945, but July 1945, haunts me. Was this small addition a silent nod beyond the Olympian tranquility of the printed page to those who knew the meaning of this date to reflect on the Leipzig of this moment, a shattered city, first occupied and now fully abandoned to a vengeful army, angry, armed men roaming its rubble-strewn streets? He may have inhabited a post-apocalyptic nightmare, but he was still the Professor of Classical Philology and put his hand to paper to complete his translation of the Antigone.

§22. I chose the three examples cited above precisely because I encountered them in my regular work researching Homeric Epic and Sophocles. I was not looking at broader cultural materials to explore the reception of Ancient Greece and Rome. I was pursuing scholarly questions and encountering moments that teleported me to linguistic and cultural settings that were still part of the modern world but that were well beyond my experience. For me, one of the joys of studying Greco-Roman culture, even in the most traditional ways, is that I constantly experience these moments where I am knocked off course from my scholarly thread and a new world opens before my mind’s eye.

§23. These historically charged moments, however deeply they affect me personally, reflect an intellectual culture that, for our time, is paradoxically both too narrow and too broad. This model of the study of Greco-Roman culture is too narrow because moving through networks of publication in English, French, Italian and German about sources in Ancient Greek and Latin keeps me anchored within a European center of gravity. In fact, a focus on these four modern languages is not even European in scale—the EU has 24 official languages, and these do not include contested languages such as Catalan. The four languages that I was trained to view as the languages of record reflect only a handful of hegemonic languages—I was not trained to feel that I needed to understand Spanish, much less Polish, Rumanian, Dutch, Croatian (still covered under Serbo-Croatian when I was in graduate school). The study of Greco-Roman culture takes place beyond Europe, North America and the anglophone world. There has been a century of scholarship about the Greco-Roman world published in Arabic since Taha Hussein founded the Department of Greek and Latin Studies at the University of Cairo. Work goes on in Brazilian Portuguese and New World Spanish and this scholarship should be fostered. New students of the Greco-Roman world have emerged in China, South Korea, and Japan. We should welcome the interest and the voices from around the world. We can label ourselves descriptively as Greco-Roman or Greek and Roman Studies or something similar. But if we want to hold onto terms such as Classics and Classical Studies we must consciously and tangibly break from our Eurocentric intellectual networks.

§24. But if the traditional scholarly space of Greco-Roman studies reflects a narrow set of hegemonic European languages, that space is already crushingly broad. In spring 2021, the Princeton Classics Department made headlines and provoked vigorous debate when they announced that Classics majors would no longer be required to study either Greek or Latin.[19] The goal was to open the field to a more diverse range of students. Whether or not we think Princeton made the right decision, their decision reflects the fact that it is difficult enough for students to learn Greek and Latin and very difficult indeed to learn enough of the languages to read broadly. If we consider that, in the traditional model, advanced students of Greco-Roman culture should be able to read not only two ancient languages but also scholarship in three modern languages, the problem becomes almost impossible. In international conferences of Greco-Roman studies, speakers are often free to deliver their papers orally in English, French, German or Italian. Audiences are expected to sit quietly and at least feel guilty that they have not developed the ability to understand everything that is being said.

§25. Students of some European countries with strong multilingual educational systems at the primary and secondary levels may be able to accomplish this. It is possible to develop some command over French, German and Italian if students have an opportunity to focus one French or German in secondary school, the other language as undergraduates and then perhaps work in even a semester of Italian—combined with Latin and French, a semester can be enough to get started. But that, of course, does not account for coursework mastering Greek and Latin. For the most part, students born in an anglophone, monolingual society will have a hard time ever becoming proficient in Greek, Latin, French, German and Italian. Most professional scholars develop just enough knowledge to pass departmental reading exams. Covering scholarship in languages other than English requires so much effort that most American scholars concentrate on scholarship in English. But, of course, concentrating on scholarship in our native language defeats one of the major advantages of Greco-Roman studies as a transnational field that scholars speaking many languages share in a way that is possible for no modern language. I cited scholarship above in German and Latin and I am reasonably comfortable reading and understanding French and Italian, but in all honesty I need to make an extra effort to keep track of scholarship outside of English and the extra effort of reading other languages means that I will probably always have an anglophone bias—so long as I read and conduct scholarship with the traditional, wholly manual methods in which I—and indeed virtually every student of Greece and Rome—has been trained. There are certainly a number of colleagues from the anglophone world with wider linguistic competence and I envy their skills but I fear that I am more advanced than most.

Greco-Roman Studies in the 21st Century United States

§26. In the section above, I picked three moments of technical scholarship where the historical moments in which they were composed not only informed my point of view but moved me: the years immediately preceding and following the unification of Germany in 1871, post-war, influenza-ridden Paris in 1919, and Leipzig occupied by the Red Army in July 1945. In the following section, I will try to articulate my own general attitudes to Greece and Rome and the recommendations that I will make for refashioning our libraries, reimagining our audiences, and redefining the social contract upon which paid positions for the study of Greece and Rome depend.

§27. I will begin by stating that I cannot, in fact, link one fundamental attitude to any moment in time: my belief that Classics and Classical Studies cannot be reduced to the study of Greece and Rome. It extends at least since 1982 when links between Greek archaic poetry and topics in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Hittite texts convinced me that I could only understand early Greek culture if I saw it as a late phenomenon emerging under the influence of far older and more cosmopolitan cultures. The surviving old Babylonian versions of the Gilgamesh epic date from the 18th century BCE and probably derive from Sumerian poems that took shape centuries earlier (c. 2100–2000 BCE)—1,000 or 1,300 years before the conventional dates associated with the Homeric epics (mid 8th century BCE).[20] For me, the Gilgamesh epic in its later, more commonly read version,[21] seemed to address in two separate compositions grand themes of the Iliad (heroic comradeship and loss) and of the Odyssey (the journey beyond the world of humanity). The more I read about female figures from the underworld such as Innana, Ereshkigal and Ishtar, the more I saw them as prototypes for Persephone, Circe and Calypso. I began studying Sumerian (2 years), Akkadian (3 years), and Hittite (1 year) because I simply did not feel that I could write a dissertation if I relied wholly upon the English translations.[22]When in 1985 I began work on what would become the Perseus Digital Library,[23] I wanted to make sources in these languages intellectually more accessible and to enable scholarship that explored it as a cultural continuum. I would at the time have embraced a comment that I heard many years later from Dimitri Gutas, then a Professor at Yale working on Greco-Arabic studies: the West begins at the Hindu Kush.

§28. I had also already developed as an undergraduate a discomfort with European cultural hegemony. All my DNA (as far as I know) comes from Western Europe. I was a student at Harvard. But I observed vicious comments directed at my teachers by European counterparts (one particularly extreme figure, according to two sources, called for a “public hanging” of one of my professors). I knew that I would never develop mastery in more than a few small specialties within the vast field of Greco-Roman studies (and I was quite correct). I believe that the European Union, for all its failings, is still one of the greatest achievements of humankind—an unthinkable triumph, however fleeting it may prove. I was Professor of Digital Humanities at Leipzig and came to appreciate the Germany that I crisscrossed on Deutsche Bahn over more than six years. In devoting myself to the traditional study of Greece and Rome, I committed myself to exploring centuries of scholarship in English, French, German and Italian, but overwhelming as Europe was and much as I owed Europe culturally, I was not a European.

§29. As I was composing this piece, a colleague surprised me by quoting on Twitter something that I had written in an exchange with him 1993: “I might point out that the APA [American Philological Association] had its first meetings (1869), as many people talked about native American languages as about Greek and Latin. We had the opportunity to develop a vision of classics that drew upon the peculiar circumstances of our side of the world and missed our chance. If anyone systematically pursued cross-cultural comparison between Greece and Mayans/Lakota/other New World people, the world would not only be fascinating but would do quite a bit for the reception of our field.”[24]

§30. Having framed moments in scholarly publications that connect to historical moments, I will shift now to the current moment. My goal is to explain how the events of 2020/2021 helped shape the recommendations that I will make for developing a generation of libraries and of the publications that fill them to advance the role that Greco-Roman culture can play in the intellectual life of humanity. My basic outlook has not changed—I have long believed that professional scholarship only matters insofar as it has impact outside of scholarly circles and that we need to reinvent the study of the past in light of new technologies, that those technologies disrupt our assumptions about the audiences we can reach and the questions that those audiences can explore, and that we need to rethink our study of the past in light of our own values.[25] But if the broad perspective remains the same, possible next steps have changed, both because of work that has been completed in the humanities and the computational sciences and because of changes in society as a whole.

§31. First, I will only touch upon one major, and widely noted, impact of the pandemic. Reliance upon digital tools, including digitized publications and videoconferencing for communication, received a tremendous boost. Even the most digitally inclined of us will be relieved to be able to spend time in face-to-face meetings with students and colleagues but now I can expect almost all my colleagues to be ready to meet at a distance. For me the change is particularly dramatic because I divided my time between Leipzig and Germany from 2013 and even now have students there. I could not have managed a transcontinental research team in the same way without video-conferencing—someone was always on the other side of a screen and a 5- or 6-hours difference in time. But it was often a struggle to get others to join us in this medium, with skeptical friends and colleagues often struggling to set up Skype or Google Hangouts (the main systems that we used). Now I cannot remember the last time someone I wanted to talk to could not use one video-conferencing system or another. Time zones have replaced geographic time zones as the major challenge to on-going collaboration. Small disciplines like the study of ancient languages must exploit our ability to reach far wider potential audiences to develop new audiences, including both students enrolled in traditional institutions and a broader community of informal learners. More extensive discussion of this topic belongs to another paper.

§32. Events beyond the pandemic, however, also disrupted my plans. First, I had already for years argued that if we are to use the terms Classics and Classical Studies, we must use them in the most expansive and inclusive senses possible—not just Classical Greek and Latin but also other languages from beyond Europe such as (but not limited to) Classical Chinese, Sanskrit, Classical Arabic and Persian, the ancient languages of Egypt and the Near East, and the K’iche Mayan that preserves the Popol Vuh.

§33. For my part, I had worked to include Arabic. The initial impulse came from my colleague, Malik Mufti, a professor of Political Science at Tufts who audited my advanced Greek course on Thucydides in 2005/2006. Over coffee, when we discussed the deeply problematic role of the United States in Iraq and the Arabic speaking world, I talked with Malik about what I might be able to do to make some sort of positive, however modest, contribution. The idea emerged that I should learn Arabic. I had avoided Arabic as too difficult and not practical—I had always felt I could never work on Aristotle because, somehow, I got the idea that that would have required that I learn Arabic. But Malik had found time to participate in my Thucydides class and was not afraid to work directly with arguably the hardest Greek in the curriculum. In part inspired, in part shamed, I decided that I would try.

§34. I had known something about the translations of Greek texts into Arabic, but Malik explained to me that the translation movement looked back to a particularly cosmopolitan stage of Islamic thought. Promoting the study of ancient Greek in Arabic would be something that could recall this cosmopolitan history. Even if the impulse came from someone from a Western university like me, that impulse could point back to Islamic engagement with Ancient Greek science and philosophy. In 2009, in preparation for a lecture at the Department of Greek and Latin Studies at the University of Cairo, I read that this department included among its areas of focus both the translation movement from Arabic into Greek (c. 800–1000 and centered in Baghdad) and a later translation movement (c. 1200–1300 at Toledo and Sicily) from Arabic into Latin that reintroduced much Greek science and philosophy as well as original Arabic research to Western Europe.[26] While I had dimly known something about this circulation of ideas, I had not appreciated its importance. The European renaissance would not have taken the form that it did—indeed, it might not have happened at all—without the impulse of ideas transferred from Arabic into Latin. While some of my colleagues and students had, like me, some idea that this had happened, I did not think that the immense importance of this story had made itself felt. And it was a story that a department of Classical Studies could fully tell if it could support Classical Arabic as well as ancient Greek and post-classical Latin.

§35. I sat in on classes on Modern Standard Arabic at Tufts from 2006 through 2011. Our curriculum teaches Arabic as a spoken language, and I did get to the point where I could express most ideas in Arabic. When, in 2009, I lectured at the University of Cairo, I managed to labor through my lecture in Arabic (which I had written with extensive help from Valerie Anneschenkova, who ran the Tufts Arabic program). I was shocked to discover that there were 80 students in the advanced Greek class. Not so much earlier, I had been unaware that there was a department devoted to the Greco-Roman world in Cairo. Then I saw a program with more language students than any institution of which I was aware in the United States. The great Egyptian novelist and intellectual, Taha Hussein, returned from study in France determined that Egyptians would assert their claim to 1,000 years of Greco-Roman culture and, in 1925, he was responsible for the foundation of the Department of Greek and Latin Studies at what is now the University of Cairo. Egyptians have studied Greek and Latin for almost a hundred years. As of 2014, Usama Gad, Assistant Professor of Papyrology and Greco-Roman Studies at Ain Shams University in Cairo, estimated that there were 2,000 advanced students of Ancient Greek and Latin.[27] Generations of scholars have published on the Greco-Roman world in Arabic. Almost thirty years of publications from the journal of the Greek and Latin Studies department at the University of Cairo is openly accessible today.[28] All this work is, essentially, unknown and, for most experts outside the Arabic speaking world, unknowable. In January of 2011—as protests were beginning in Tunisia that would become the Arab Spring, I visited the University of Cairo again and interviewed students about why they chose to study Greek and Latin. They spoke of their interest in the subject—but they were really most interested in what their counterparts at Tufts and elsewhere were like. They were eager to reach out and they saw their subject as a shared topic that would open new conversations with other young people about the past that we share and the future that they wish to build.

§36. When I returned from Egypt, I gathered up my courage and proposed to teach in fall 2011 a course on Aristotle’s Poetics in the Greek original, as it appeared in the middle commentary by Averroes, the Latin translation of Averroes by Hermannus Alemannus (literally, “Herman the German”), and (briefly) William of Moerbeke’s translation from the Greek into Latin completed in 1278.[29] Of seven students, three had studied Greek and/or Latin, three had studied Arabic, and one had studied all three. The students were tasked with explaining how the language in the version they understood worked to their classmates so that together they could compare the three different versions of Poetics. They recorded their interpretations using a technology called translation alignment (with the first version of the Alpheios.net alignment system), linking, where appropriate, words and phrases in source text to their corresponding elements in the translation. I was reassured when I found that members of the class were able to see, much more clearly that I had expected, how the different language versions related to each other even when they could not read the Arabic.

§37. In spring 2012, however, I was offered an Alexander von Humboldt Professorship in Digital Humanities at the University of Leipzig with funding to build up an extensive research team. After extensive discussions, I ended up splitting my time between Tufts and Leipzig, remaining a faculty member of Leipzig from April 2013 to October 2019. I was unable to build on the teaching and nascent research with Greek and Arabic and set this work aside. Nevertheless, despite the fact that my personal focus had to change, there were several longer-term results from this work.

§38. First, we were able to have several works in Arabic manually keyed-in. While Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for Arabic (and for Ancient Greek) has improved dramatically in the subsequent decade, manually keyed transcriptions still provide a substantial advantage if our goal is to create curated files encoded with XML markup from the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI).[30] The Alpheios Project, which has done pioneering work developing interactive reading environments for ancient texts, converted several of these works—roughly 4 million tokens of Arabic—into CTS-compliant, TEI XML and published them on GitHub.[31] In addition, Alpheios devoted considerable energy to structuring Edward William Lane’s 1863 Arabic-English Lexicon, a crucial reference work for Classical Arabic that, when linked to the digitized texts, can greatly enhance the usefulness of the Perseus/Alpheios digitized Arabic texts for English speaking readers.[32]

§39. Second, I worked with Mark Schiefsky, Professor of Classics at Harvard (and, as of July, Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies) on a Digital Corpus for Graeco-Arabic Studies (https://www.graeco-arabic-studies.org/), an openly licensed, bilingual collection with Greek source texts and their Arabic translations. For those who simply wish to perform close reading and to search each corpus, the collection is already valuable. David Bamman (then a senior researcher at Perseus but now an associate professor in the School of Information at UC Berkeley) had generated fascinating results by automatically comparing Greek and Latin texts with English translations.[33] We were unable to replicate those results with Greek and Arabic ten years ago but rapid progress, particularly enabled by increases in hardware power and the availability of computationally demanding methods from Deep Learning, promise to open up this corpus for automated analysis.

§40. Third, while I was myself no longer in a position to advance Arabic in the Department of Classics, I was in 2012 able to get a postdoc position in the Department of Classics for Maxim Romanov, an expert in Arabic and Islamic Studies and Digital Humanities. Maxim has emerged as a leader in Digital Arabic Studies and then, after his two year term at Tufts completed, I welcomed Maxim to my research group in Leipzig, where he remained for two years before assuming a position as academic assistant (equivalent to non-tenure-stream assistant professor in the US). Maxim served as a catalyst for projects in Europe and the US. At Leipzig, Maxim established the Islamicate Text Initiative (OpenITI),[34] which set out to organize, to expand upon, and to redistribute in systematic format thousands of Arabic texts that have been circulating in a range of formats—roughly a billion words of Arabic. OpenITI has, in turn, helped foster three different major projects. First, Sarah Savant and Maxim Romanov were able to win major support from the European Research Council (ERC) for the Kitab Project,[35] which applies a range of automated methods to analyze Arabic sources that are far too large for exhaustive close reading and that draws upon methods for text reuse detection to identify relationships between Arabic texts far more extensively than has ever before been possible. In automatically analyzing text reuse, Kitab collaborated with David A. Smith, who was chief developer for Perseus before getting his PhD and a tenure-stream (now tenured) position as Associate Professor of Computer Science at Northeastern University. This led to US funding from the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities to expand work that Maxim Romanov had begun at Leipzig with then PhD student (now Dr.) Benjamin Kiessling to improve OCR for Arabic script publications.[36] A second PhD thesis, submitted by Masoumeh Seydi in summer 2021, explores various techniques for extracting, expanding and visualizing geospatial data about the Islamic world from Arabic sources.[37] The work by Maxim and Masoumeh has also led to the creation of al-Ṯurayyā Project: a gazetteer and a geospatial model of the early Islamic world.[38] Finally, Maxim won funding from the German Science Foundation (the DFG) to found his own Independent Junior Research Group (an Emmy Noether Award). The project’s title is “The Evolution of Islamic Societies (c.600–1600 CE): Algorithmic Analysis into Social History.” Its goal is to “produce six interconnected research publications: two PhD theses; a methodological handbook and a collection of articles—both co-written with international partners; a Longue Durée Atlas of Islam; and the PI’s monograph that will conclusively present the [project]’s results and its novel computational approach. Last, but not least, the [project] will produce an open and expandable online research ecosystem, Master Chronicle, which will allow scholars in the field to engage in various modes of close and distant reading of the Arabic historical corpus.”[39]

§41. Fourth, at Tufts the work that I had done on Greco-Arabic studies and that Maxim developed as a postdoc caught the attention of Vickie Sullivan, who took over as chair of the department when my divided time made it impossible for me to continue. In 2014, Vickie drew up a successful proposal for a tenure-stream position in Greco-Arabic studies and Tufts became one of the few institutions to have a position dedicated to this crucial and far underappreciated area. Riccardo Strobino, a scholar with a focus on Avicenna who works on Greek, Latin, and Arabic, joined the department as a Mellon Bridge Assistant Professor of Classics with a secondary appointment in Philosophy. That appointment brought classical Arabic into our department with a tenure-stream appointment that could extend decades into the future. Tufts is the first university in North America of which I am aware that located a tenure-stream position in Greco-Arabic studies in a Department of Classics (subsequently renamed, Department of Classical Studies). I had chosen to work on Arabic because I had, as an individual, thought it was a logical thing to do. The appointment of Professor Strobino formally made Arabic a central classical language at Tufts University, establishing once and for all a model of Classics and Classical Studies that could move beyond its Eurocentric roots.

§42. The general topic for the research group at Leipzig was Global Philology. Data that we collected and software that we produced had to be available under an open license. A major focus was on promoting bilateral exchanges among different cultural communities, and that rubric was designed to invite a range of different topics. PhD student Maryam Foradi played a prominent role, with her own research serving as a catalyst for that of others. A professional translator between Persian (her native language) and German, with an MA in Translation Studies, Maryam allowed us to explore exchanges with Iran. For me, this was a topic of personal interest as I had followed the downfall of the last Shah while I was an undergraduate. Like many others in the US, I saw the Shah as a brutal figure and felt that his departure would be a positive thing for Iran. I then sadly watched the Islamic government seize upon the United States as a centralizing force, both because of its past actions and because of its role as an ongoing symbol of ideas that threatened and outraged the regime. I was also conscious, as I watched Iranian students my own age storm the US embassy, that, had I been born in Iran, I probably would have been among them. I had long cast about for mechanisms to begin conversations between scholars from Iran and the US. In the years before 2010, I had searched, unsuccessfully, for ways to host a conference in a country which both Americans and Iranians could easily visit. The topic would have been Marathon, 2500 years later, and how this event and the subsequent Persian Wars have framed the relationship between Iran and the West. The question would have been how to rethink that relationship.

§43. When Maryam joined our group at Leipzig, we began to consider the role of ancient Greece in Iranian culture. I learned, for example, that what we call the Persian Wars are known in Persian as the Athenian Wars. Insofar as students in Iranian schools learn about them, they are represented as punitive expeditions provoked by Greek, in general, and Athenian attacks and atrocities. Maryam performed sample online surveys on attitudes of Iranians to ancient Greek culture. The results can only be preliminary but those who chose to reply did not have very positive thoughts and Alexander was hardly viewed as Great. Greek sources provide a crucial window onto ancient Iran, but almost no direct translations from Greek into Persian exist—such translations as are available are based on translations in languages such as French or English. Maryam and I were able to detect substantial noise in the transmission.

§44. Maryam worked in an early project at Leipzig exploring ways to use exhaustive morpho-syntactic annotations (the Ancient Greek and Latin Dependency Treebanks that David Bamman had begun when he was at Perseus in 2006),[40] and links between words and phrases in source text and translations, using the same alignment editor developed by Alpheios that I had used in my course on Aristotle’s Poetics in Greek, Arabic and Latin. We focused particularly upon a subset of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, the summary description of Greek history between the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, for which Francesco Mambrini, as part of a join German/US project, had developed visualizations of events and entities in the text.[41] What we found was that, without any formal study of the language, Maryam was able to use this scaffolding to understand the Greek text and to create a translation that was far more reliable than the indirect translations and often closer to the original than the direct translations from Greek to English that we analyzed. More importantly, unlike the English translations, Maryam’s Persian translation linked back to the Greek text and its exhaustive annotation. Persian readers of Maryam’s translation would be far better placed to assess the relationship between the Greek and her Persian translation than would ever be possible for anyone working with the most scholarly direct translation into English by itself.

§45. Maryam’s work made it clear that we could not measure the value of a translation by its independent quality because no one who depends entirely on that translation could independently assess its quality. The true value of a translation depends upon its inherent quality and our ability to explore how the translation relates to the original. This is a foundational change: translations no longer exist—or should exist—as linguistic backboxes but should serve as front ends to their sources and to an increasing network of annotations that lay bare the linguistic structures and cultural backgrounds of the text.

§46. At this point, subsequent research divides into two components: making Ancient Greek accessible to Persian speakers and making the Classical Persian of figures such as Ferdowsi and Hafez accessible to English speakers. If I simply advocated that Persian speakers should learn Greek, I feared that I would implicitly convey the message that the classical literature of Europe was more important than the classical literature in Persian. I felt that my best response was to support both the study of Ancient Greek in Persian and of Classical Persian in European languages such as English. The goal was to establish an exchange of ideas and a conversation across cultures. I was already blessed to have Saeed Majidi as my PhD student in Computer Science at Tufts. As noted above, I was privileged to become the official PhD advisor for Masoumeh Seydi. Her work with Maxim Romanov focused on analyzing geospatial information in Classical Arabic but she was also from Iran and spoke Persian (as well as Azeri). Dr. Fatima Fahimnia, Professor of Department of Information Sciences & Knowledge Studies at the University of Tehran visited us at Leipzig in the 2018/2019 academic year and that visit was instrumental in establishing the University of Tehran Digital Humanities Laboratory.[42] In 2019, Farnoosh Shamsian, who had an MA in historical linguistics from the University of Tehran and who had been teaching Ancient Greek to Persian speakers, received a DAAD fellowship to work on a PhD at Leipzig on developing a platform for studying Ancient Greek and (insofar as is also feasible) Classical Persian that could be localized for speakers of English and Persian.

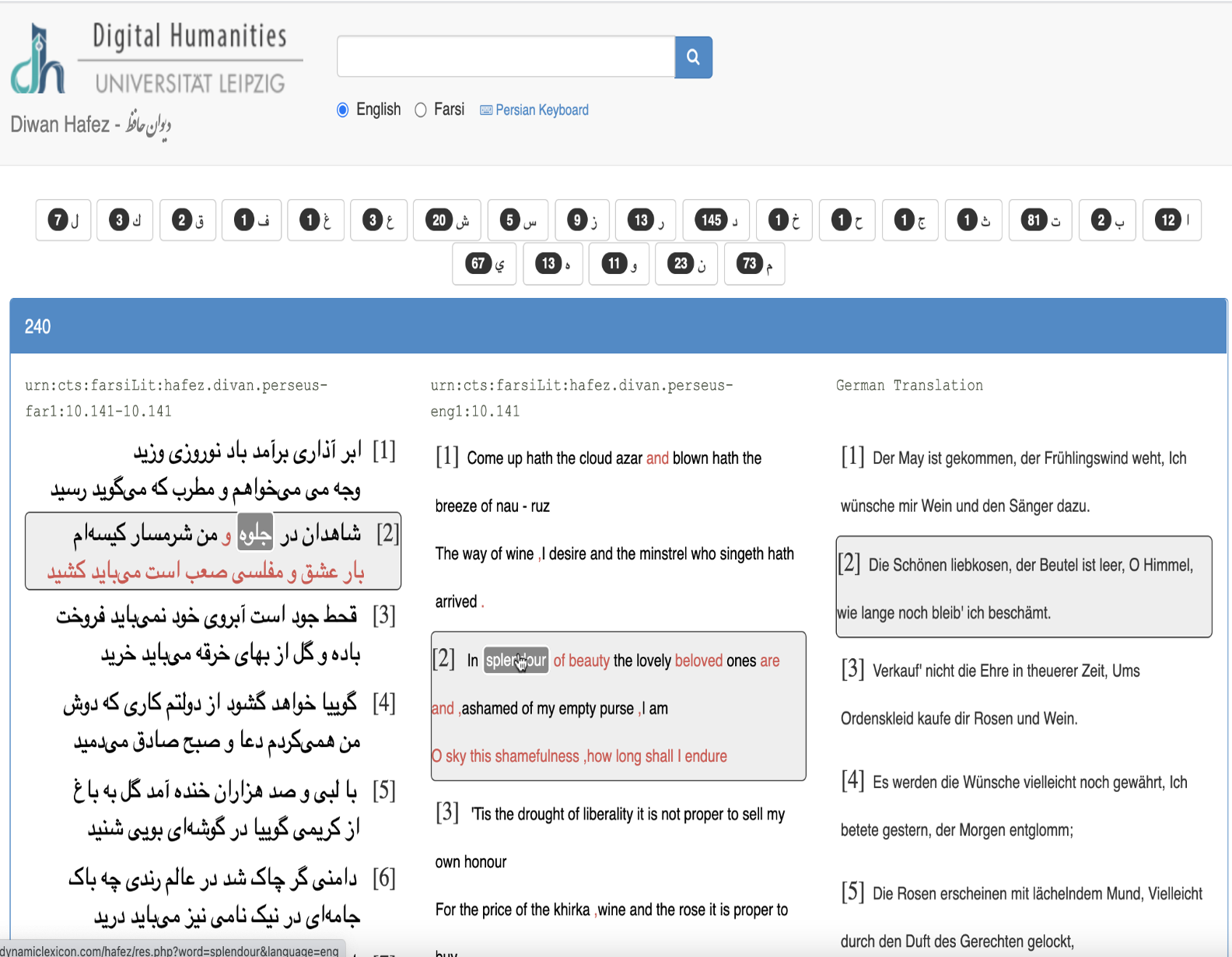

§47. Maryam Foradi focused on the broader question of how we could make Persian poetry more accessible to speakers of English. Iranian students learn in school that, in composing his vast epic poem on the pre-Islamic history of Iran, the poet Ferdowsi kept the Persian language from giving way to Arabic[43]—even so, a substantial amount of Persian vocabulary derives from Arabic. The poetry of figures such as Hafez, Rumi, and Omar Khayyam play central roles in defining cultural identity within the Persian speaking world. Translations and adaptations of Persian poetry into European languages have been popular for centuries.[44] New translations of Persian poetry command substantial audiences in the United States. In the 2016 MLA Report on Enrollments in languages other than English, 73 institutions reported enrollments in Persian, vs. 990 for German (which has roughly the same number of speakers), 567 for Arabic and 479 for Ancient Greek.[45] Of those institutions teaching Persian, most instruction almost certainly focuses on the contemporary spoken language. It is not clear how many American students of Persian have an opportunity to work in the original with classical Persian poetry outside of a handful of excerpts introduced to provide some context.

§48. Maryam chose in her dissertation to explore the impact of one novel form of annotation: parallel text alignments that link words and phrases in the source text with words and phrases in the translation. She compared two groups: Iranian students in an MA program on German and German students with a knowledge of Arabic (and an ability to adapt quickly to the nearly identical character-set of Persian) but with no knowledge of the Persian language. She assigned the same task to both: given word level alignments between the Persian poetry of Hafez and an English translation, they had to determine the best alignments between the same Persian poem and a German translation. Neither the English nor the German translations were very literal and there were no linguistic annotations explaining the part of speech or grammatical function of the Persian words. The German students needed to exercise judgment and make guesses about how the Persian worked so that they could align the Persian to the German.

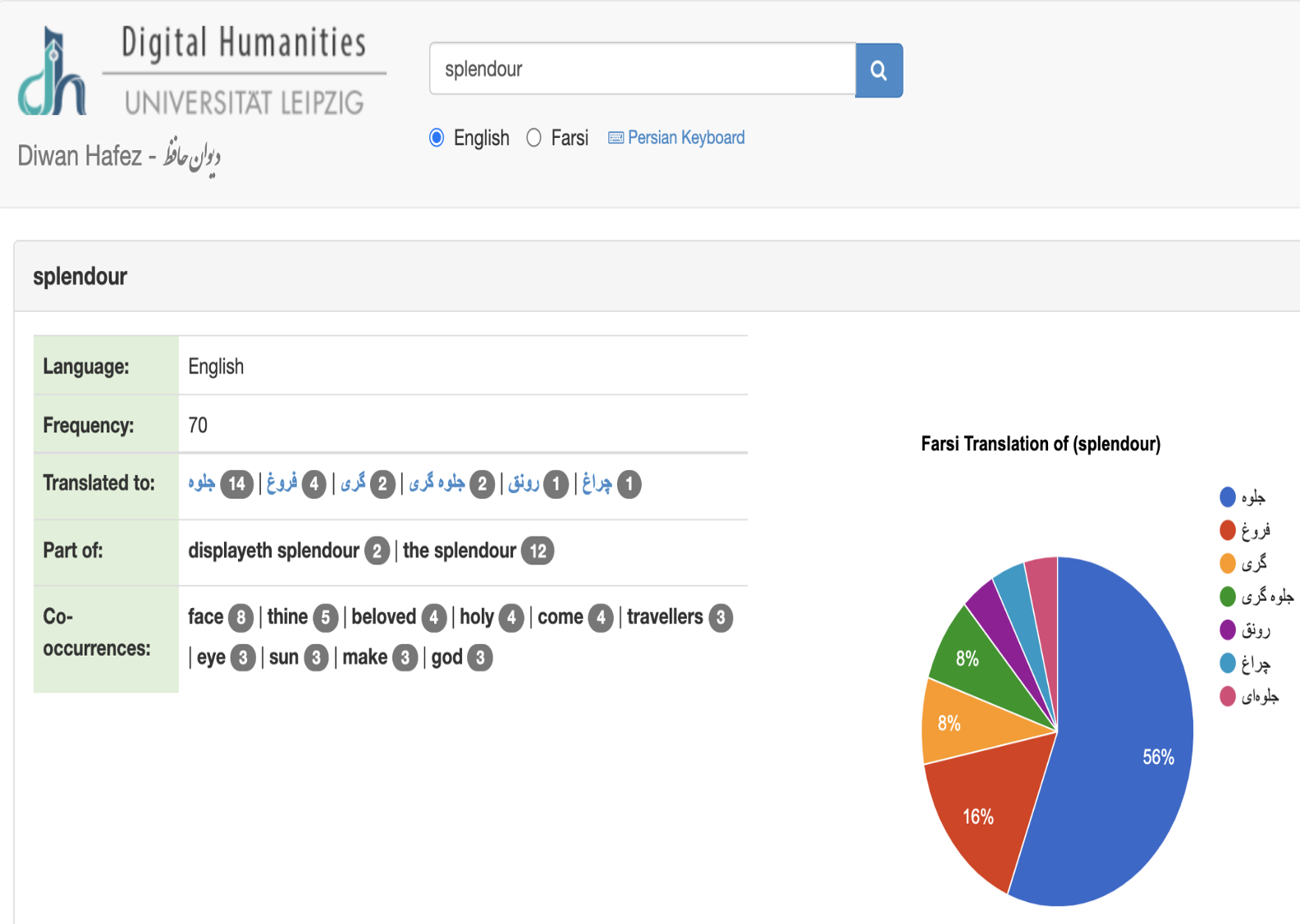

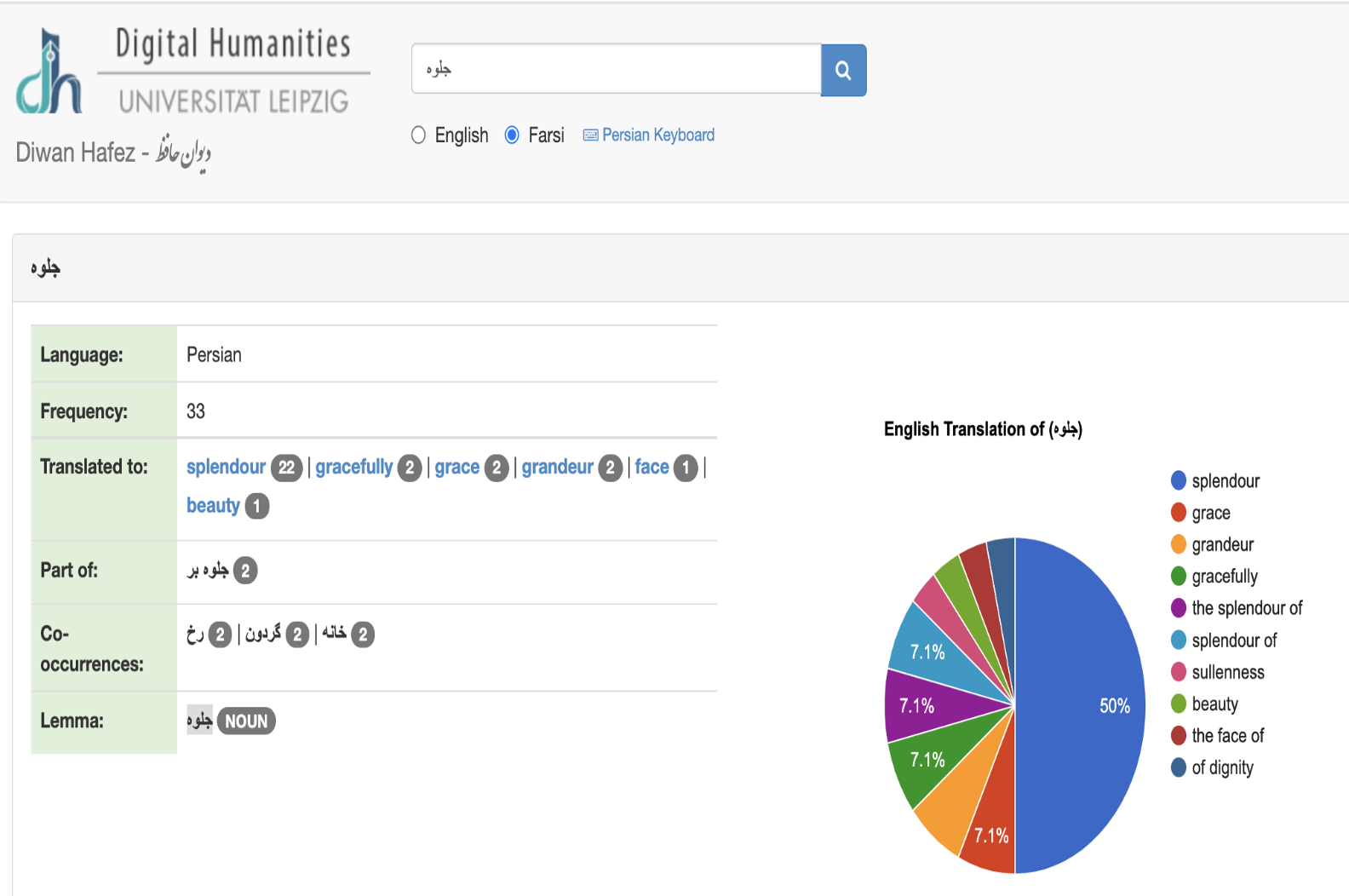

§49. Three findings from this work are relevant here. First, when the Persian/German alignments of Iranians with advanced knowledge of German were compared to those produced by the Germans with no knowledge of Arabic, the accuracy of the two groups was comparable (indeed, the German alignments were slightly better). This means that, at least in the case of Persian, the Persian/English alignments allowed readers to link the German to the Persian whether they knew Persian or not. This result is important for at least two reasons. On the one hand, manual alignments are useful in themselves as they can be used to illustrate the different ways a Persian word has been translated into English (or German) or the different Persian words behind a single English (or German) word. The English word “splendour” (selected in Figure 4), for example, translates six different Persian words.

If we then examine the Persian word (جلوه) that is translated as “splendour,” we can then see how it was, for its part, translated into English.

The Persian word is most commonly translated “splendour.” It also appears as “grace,” “grandeur,” “sullenness” and “beauty.”

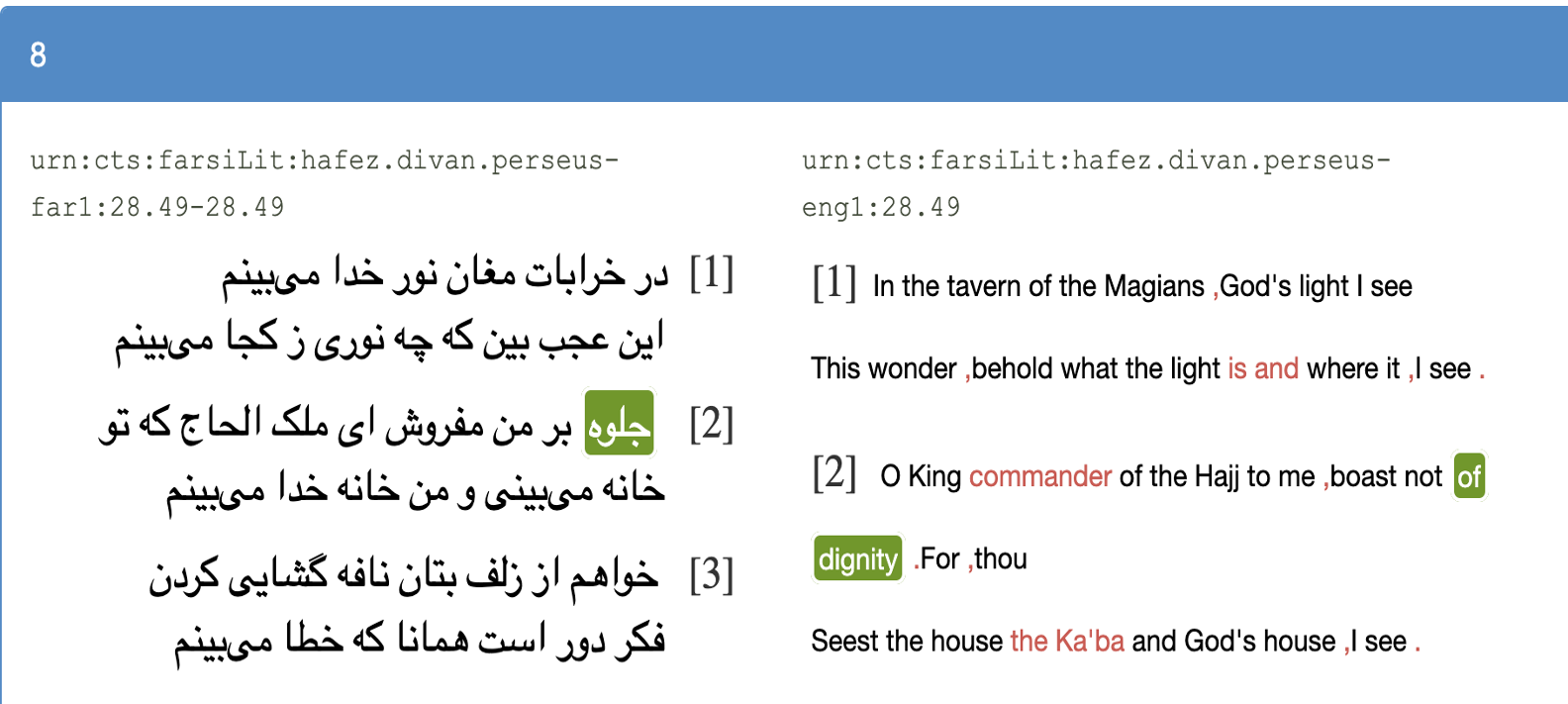

§50. If, of course, we really want to develop our own understanding of what words mean, we need to examine how they are used in multiple contexts. Once we have an aligned translation, we can implement bilingual searches that allow readers to explore the contexts for words in a language that they do not know.

Figure 6, for example, shows a passage where the Persian word is translated as “dignity,” rather than “splendour.” The bilingual search points to another reason why alignments are useful: not only can we find all the passages where the Persian word appears and see how that word is translated in context, but we can then use the other alignments to explore the words of each sentence in which the Persian word appears.

§51. The second finding from Maryam’s dissertation that I would cite here involves incidental learning that took place when the German annotators aligned the Persian to the German translation. I would have expected that the German annotators would have taken only a relatively cursory look at the Persian words as they were aligning them to the German. While they could easily learn to read the Persian variation on Arabic script, they could not convert the symbols before them into their fully vocalized forms because Persian, like Arabic, does not normally include short vowels. I expected that the Persian words would have made little impact on the annotators. In fact, the annotators were able to learn and retain the meanings of words.

§52. Maryam tested what annotators learned under two conditions: (1) paying attention to words as they aligned them and (2) studying the words with electronic flashcards. In the short run, the traditional flashcard method was more effective—the flashcard students tested higher on a vocabulary test administered the next day—but, in the longer term, what students learned from the alignment exercise remained just as firmly fixed in memory: when tested two months later, the flashcard and alignment learners remembered essentially the same amount. Presumably, a combination of the two methods would be most effective and that would be an interesting subject for a follow-on study.

§53. The final result was an incidental finding but suggestive: the participants spent more time on the alignment task and enjoyed it more. Where flashcards may be more effective in the short run, they are a straightforward learning exercise that demands concentration and discipline. Aligning a source text to a translation is, by contrast, a puzzle. The fact that it is not always possible to find correspondences between words and phrases in the source text and the translation can make the exercise even more of a puzzle and more engaging. If, given adequate scaffolding, individuals can effectively align translations in a language that they do know with sources texts in a language that they do not and if the resulting data serves a useful purpose, we could design alignment exercises as games by which citizen scholars can both contribute and learn. Such tasks, in turn, begin to open a field and give a much wider community the chance to contribute meaningfully and to develop a sense of ownership. The fact that incidental learning takes place as well opens possibilities for intellectual development. Ultimately, the goal would be to create a chain of tasks, each of which both generates data that is useful for the field and teaches the annotator something, and which together can lead anyone from casual interest in a topic to as much mastery as their growing interest, their time and their abilities allow.

§54. Translation alignment is, of course, not the only kind of annotation that we would choose to reveal the workings of a text in an unfamiliar language. I worked on morphological and syntactic annotation long before I realized what could be done with translation alignments. When translation alignments are coupled with explanations for the morphological and syntactic function of each word in a source text, the two resources become far more powerful. Readers can begin to see where and how source text and translation align and diverge. The point is not that aligned translations are optimal on their own. What surprised me from this work was that it reminded me how useful aligned translations on their own nevertheless could be, even before we could add more categories of annotation.

§55. Persian poetry offers several advantages. First, there are numerous, very popular contemporary translations. US Fair Use law would allow us to republish some intellectually justifiable subset of a copyrighted translation:

“Under the fair use doctrine of the U.S. copyright statute, it is permissible to use limited portions of a work including quotes, for purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, and scholarly reports. There are no legal rules permitting the use of a specific number of words, a certain number of musical notes, or percentage of a work. Whether a particular use qualifies as fair use depends on all the circumstances.”[50]

In my view, every serious review of a translation should, as soon as the infrastructure is available, be accompanied by quotations aligned to the source text, with a constructive analysis of the relationship between the two. A number of people would, I suspect, have a passionate interest in probing that relationship—especially if they could explore alignments between the rest of a work (such as the Divan of Hafez) by using an openly licensed modern language translation.

§56. Second, there are many compelling performances in Persian of individual poems and sections of larger poems (like the Shahnameh) available in YouTube and other venues. These recordings can be aligned to transcriptions of the Persians (which are, in turn, aligned to translations). The Persian transcription may not include the short vowels and the short vowels can be hard for those who do not know Persian to pick out with precision,[51] but at least some of those who are enchanted by English translations will become captivated by the sound of the Persian and will listen over and over until they have memorized the Persian version.

§57. In late spring 2020, I was preparing for a sabbatical that I would spend, in part, at the Center for Hellenic Studies. I had planned to focus on building out what I called a “Smart Homer,” a digital edition with a growing collection of machine actionable annotations that could be analyzed, recombined, filtered, and visualized to provide customized and ultimately personalized views of information relevant to particular people with particular background and particular goals of the moment. The initial use case is a reader who stumbles upon a translation from Greek, begins exploring the Greek behind the translation and then begins to internalize knowledge of the language. Customization here describes conscious choices by the user, e.g., a desire to focus on the Greek of a particular author such as Euripides or Plato or of a particular corpus such as the Homeric Epics or the New Testament. In the case of someone learning the language, such customization would prioritize the vocabulary, grammar, and morphology to be learned (e.g., someone interested in the New Testament would be spared forms in the optative mood). Personalization is more challenging and involves the identification of learning patterns and styles of users (e.g., identifying aspects of the language that prove challenging for particular users). A native speaker of a language with no definite article (such as Persian or Croatian) may well have different challenges mastering the usage of definite articles than those of a native speaker of a language such as English or German that do have definite articles (whose knowledge of their own definite article may prove to be an advantage or an impediment). We experience silent personalization every time we use Amazon or Google or some large internet platform. In our case, the challenge is to make any personalization transparent and to place the learner as much in control as possible.

Summer 2020 and Sub-Saharan Africa

§58. The addition of Classical Arabic and Persian within Classics and Classical Studies tangibly expands the use of those terms beyond Europe and those who look to Europe for their cultural roots. But engaging with languages from Europe and Asia is certainly insufficient for any sustainable model of Classics and Classical Studies in a nation with populations as diverse as that of the United States. We certainly need to attend to the cultural heritages of those who were in the Western hemisphere before European settlement. Decades ago (c. 1990), when we were both junior faculty members at Harvard, expert on Mayan studies Rosemary Joyce and I had taught a class on Mayan and Greek cultures, using early versions of Perseus to enable students to explore both the textual and visual records of Greek and Mayan culture. More recently, we had begun working with the Multepal Project, a project devoted to “provide participating students and scholars a platform to build out a thematic research collection associated with Mesoamerican society and culture, one of the primary goals of Multepal.”[52] Clearly, these collaborations are only very preliminary first steps and they do not yet address the need to consider the peoples who inhabited the current territory of the United States. This need remains unmet.

§59. At the same time, the turn to Classical Arabic and Persian opened up a clear path to engage with non-European sources from the Atlantic to the Indian subcontinent and the borders of China. But I had not yet seen a mechanism by which to engage with sub-Saharan Africa, a region from which many American citizens were forcibly kidnapped. At least two issues blocked my work. First, I still found myself too focused on chronological categories and departmental structures. I was ready to encroach upon the chronological territory controlled by departments of Medieval Studies but hesitated to move beyond the early modern period (a fuzzy concept at best, quite vaguely defined in my mind by markers such as the fall of Constantinople or the European invention of movable print or careers of figures such as Erasmus and Luther). Second, more problematically, I was afraid of opening myself to charges of cultural appropriation—and, indeed, of unconsciously justifying such charges. But this hesitation weighed upon me.

§60. A final call for sustained, substantive action came for me, as for many others, in late spring 2020. The slow, callous, and shocking murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, after so many others, most murdered in secret and silence, made me ask what I, in particular, could do that might have some tangible impact, however small. I had, of course, worked to expand Classics and Classical Studies for years but I had not seen how sub-Saharan Africa might play a role. First there were superficial considerations of chronology: I let myself think that Classics and Classical Studies should cover sources that fell under European models of the ancient world but, in engaging with Classical Arabic and Classical Persian, I had already gone beyond those chronological boundaries. More significantly, I realized that I had been afraid to move south of the Sahara because I was afraid that I would somehow not properly represent those materials. I talked with a member of the Tufts’ Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching (https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/) and decided that it was worth the risk. Ultimately, the goal was to introduce materials from sub-Saharan as part of the on-going process of rethinking what we mean by Classics and Classical Studies.

§61. My initial goal is straightforward: to develop a curriculum within Classics and/or Classical Studies in the United States that reflects the cultural heritages of the people within the US. Everyone who grows up in the United States unconsciously acquires implicit biases from the images that we confront. Simplistically put, if we experience images of people of color that are negative, we develop negative implicit biases that psychologists have measured at length and that we can measure in ourselves with online tests. One mechanism by which to ameliorate such biases is to rebalance the images that we experience, presenting more positive views of groups that receive negative treatment in the dominant culture.

§62. In Europe, Greco-Roman studies provided a space in which Europeans could see themselves as something other than subjects of the Elector of Saxony or the King of France or the Holy Roman Emperor. For those who speak English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish, the shift away from Latin as a medium of transnational communication could be a source of national pride, even if it meant that they needed to master one or more of each other’s hegemonic languages. For those who grew up speaking the other nineteen languages of the EU (not to mention languages such as Catalan or other languages that are now treated as dialects of the dialect that became the national language), the shift away from Latin was a disaster. In the early modern period, when you spoke or wrote in Latin, it made no difference whether you grew up speaking a larger language such as French or smaller languages such as Dutch or Croatian. Because it was the language of no one, Latin could become the language of everyone. The Latin language and a shared Greco-Roman culture created the possibility for Europeans to see each other as European.

§63. In my view, the rise of nationalism and of hegemonic national languages drastically undermined the great potential benefits that Greco-Roman Studies could offer. Of course, Latin and Greco-Roman Studies never reached their full potential and were always undermined by local interests. And, of course, European national identity by itself is not enough in a globalized world where everyone on earth interacts, directly or indirectly. But, as the quote from Düntzer above reflects, the study of Greco-Roman culture became a space for nationalist pride and competition. We may have developed in the 19th century the most sophisticated infrastructure for the study of antiquity that print culture could support, but as we abandoned Latin and used our claims to scholarly understanding as a means to claim our national superiority, we lost a major potential benefit from the study of Greco-Roman culture. We created an academic world, but we lost our cultural souls.

§64. Within the United States, defining Classics and Classical Studies as the study of Greece and Rome made it all too easy for the field to be institutionalized as a field in which primarily white instructors talked about Greece and Rome as the sources for Northern European culture. I can’t by myself change the ethnic composition of who teaches about Greece and Rome, but I can at least change the ethnic background of those about whom my students learn in the classes that I teach. If we can begin to change the images that they encounter and begin to attack the implicit biases to which we are all liable, then we can begin to change the visual associations upon which those implicit biases build. In my view, Classics and Classical Studies in the various nations of Europe would benefit from a rebalancing and greater inclusivity, but that is for them to decide. If we can fashion some new model of Classics and Classical Studies that is intellectually more vibrant and engaging, then others can take note if they wish.

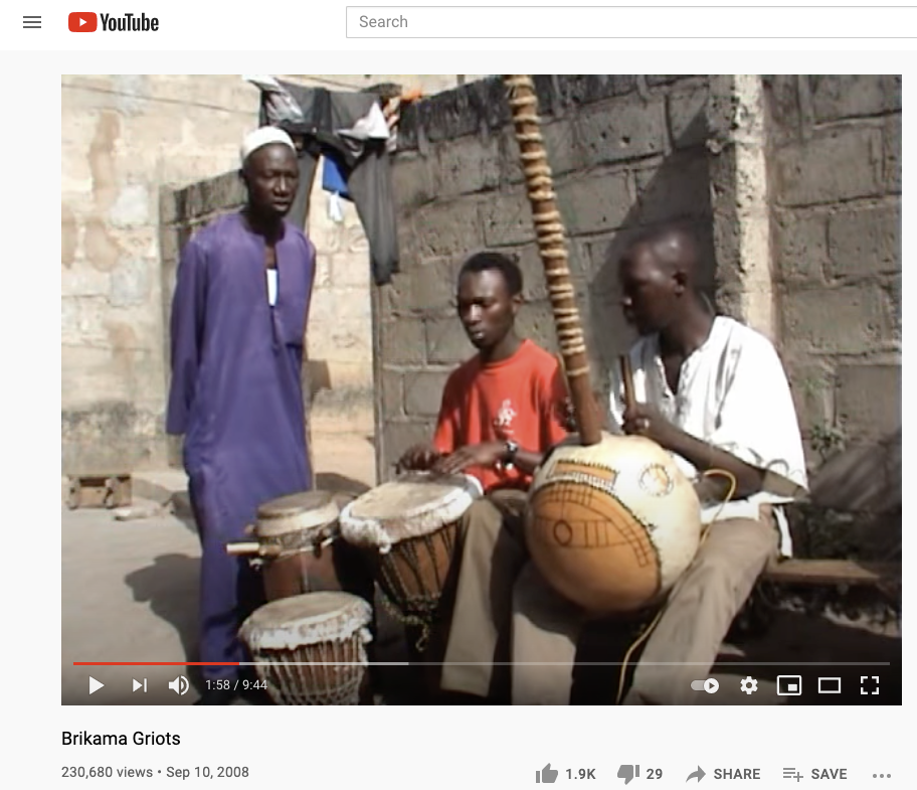

§65. I found an initial two sets of materials by which I felt that I could effectively bring sub-Saharan African sources in dialogue with Greek and Latin: West African Epic in Mandinka and Histories composed by scholars in Timbuktu that focused primarily upon the Songhay Empire. Instead of focusing my spring 2021 class about Epic poetry on the Homeric Epics and the Persian Shahnameh, I added West African Epic, with a month of West African epic, a month on Homeric epic and a month on Persian epic. In the Fall 2021 semester at Tufts, “Classics 141: Classical Historians” will focus on histories in Classical Arabic, composed in Timbuktu, about the Songhay empire and subsequent Moroccan conquest. These two corpora introduce into our curriculum complementary elements of West African cultural production: the compositions of an oral tradition in local languages (in this case, Gambian Mandinka) and those composed in a transnational, classical language introduced from outside with a role roughly comparable to that of post-classical Latin in Europe.

§66. The West African Sunjata Epic is well known and often taught in courses on topics such as world or comparative literature. While the West African productions with which I worked were from the Gambia and surely differ from the products of oral performers (griots) in West Africa as a whole, these differed from Homeric epics in several ways. They used “by and large, everyday Gambian Mandinka (GM), but with occasional non-GM features,”[53] rather than the much more separate dialect of Homeric poetry which includes features from multiple dialects and earlier periods of Greek. They also do not follow the strict metrical form that we find in the Homeric and South Slavic Epics. The West African compositions do contain formulaic constructions that are repeated with small variations and that can be compared to Homeric formulae. Like our Homeric epics, which describe a late Bronze Age world that had existed c. four hundred years in the past), the Sunjata epic also covers events from centuries in the past (c. seven hundred years when the performances in Innes were recorded). In both cases, the orally transmitted stories contain memories from earlier times but were never designed to preserve memories in the way that later historical writing, in West Africa as well as in Ancient Greece, would attempt.

§67. Preserved as part of a living oral tradition and available in many different versions, the Sunjata epic describes how Sunjata (or Sundiata) Keita established himself as founder of the Mali Empire and as a major figure in the Mande ethnic group. Most classes seem to use the version performed by jeli ngara (master bard) Djanka Tassey Condé in 1994 at Fadama, a village near the Niandan River in northeastern Guinea. David Conrad has published two versions of this, the first an (apparently) close rendering of the poetic form (2004) and a second prose version (2016) that is designed to be more accessible.

§68. I chose, instead, to focus upon the English translation of three versions that were performed in the 1960s and that were published, with an English translation, by Gordon Innes in 1974. There were several advantages to this. First, Innes provided not only a line-by-line English translation but also the Gambian original source texts on a facing page. I was able to create a parallel corpus using the e-book version from Google Books as a source.[54] I felt it was more effective to compare multiple versions of the epic and thus to communicate something of the fluidity of oral composition rather than to concentrate on one version alone. The three versions, all performed in the Gambia in 1969, were by Bamba Suso in 1969, Banna Kanute and Dembo Kanute. The traditional dates ascribed to Sunjata are 1190–1255. While Sunjata remains a largely mythical figure, his nephew Mansa Musa (c.1280–c.1337) would emerge as a clearly defined figure in the historical record, known for his immense wealth in gold and for his elaborate pilgrimage to Mecca, which did much to establish West Africa as a presence within the Islamic World.

§69. A second advantage of the Innes Sunjata is that Innes published two other bilingual editions of West African epic: Kaabu and Fuladu[55] included performances from 1969 by Amadu Jebate (Janke Waali) and Bamba Suso (Kaabu, Musa Molo, and Fode Kaba), as well as an undated recording from Radio Gambia by Be Anjsu Jebate (Musa Molo). All five performances centered on the end of the Kaabu Federation and its fall at the hands of people from the Fula ethnic group of Futa Jalon in the19th century. They thus provide us with an example of how the Griots treated far more recent events, some of which had taken place in living memory during the 1960s. In 1978, Innes published a third bilingual edition with two different versions of a story about a 19th century member of the warrior class, a nyancho, named Kelefa Saane.[56] Kelefa Saane is a bit like the title character of the Chanson de Roland: historically, he seems to have had little, if any, impact, if indeed he existed, but his story still resonates within the tradition. He is brave but impossible to control and his own homeland heaves a sigh of relief when he leaves for a distant war, never to return.[57]