2021.01.15 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. In this essay, extracting what I have learned about the meaning of the first word in Song 1 of Sappho in the overall context of studying, in previous essays, the ancient reception of Sappho, I will concentrate on the erotic power of floral perfumes—a power that is driven by Aphrodite and that is poeticized in Sappho’s songs with reference to two boy-loves of the goddess herself, Adonis and Phaon. The second of these two lovers of Aphrodite, Phaon, is featured in my cover illustration, to which I will return at a later point in my essay here. But I will start the essay below with the first of the two lovers, Adonis, focusing on two pictures that refer directly to the myth about this pretty boy’s love affair with Aphrodite—a myth that will help us understand the role of perfume in a comedy by Aristophanes known to us as the Lysistrata but apparently known to the ancient world also as the Adōniazousai, ‘Women celebrating the Festival of Adonis’. Then, after Adonis, I will follow up with Phaon, the story about whose own love affair with the goddess was retold, as was the love affair of Adonis and Aphrodite, in the songs of Sappho. In the story about Phaon, as we will see, the perfume that Aphrodite gave him had transformed him from a decrepit old man into a most beautiful boy, making him so attractive to women that that they all desired to seduce him. The ensuing seductions led to the boy’s death at the hands of the women’s threatened husbands. Similarly, when it comes to the ancient reception of Sappho, the retelling of this myth in her songs could I think make men who heard such songs feel threatened enough to suspect ‘the poetess’ of being something other than a poetess—someone they would call a hetairā. This Greek word hetairā is conventionally understood by Classicists today as referring to a ‘girl-friend’ who is sexually available to men. Such an understanding, as we will see, invites further distinctions, especially along the lines of three alternative English words: ‘courtesan’ or ‘prostitute’ or even ‘whore’. A playful observer might be tempted to remark that Aphrodite would probably not approve of any of these three words— except perhaps for the first one, ‘courtesan’.

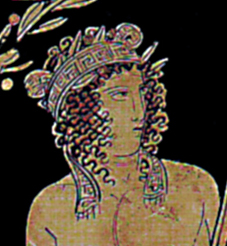

On the right: Red-figure hydria, painting by the Meidias Painter, 5th century BCE. Florence, Museo Archeologico 81948. Line drawing by Jill Robbins. Featured in this close-up is Adonis, attended by Aphrodite and by a winged Eros. Pictured is Adonis, cradled from behind by Aphrodite. Not shown in this line-drawing is an Eros hovering over Adonis and spinning a magic wheel aimed at the boy. Also attending (not shown here) is a female beauty by the name of Paidia (as indicated by adjacent lettering). For the overall painting, I cite the Beazley Archive, here.

§1. In previous essays where I have been analyzing the first word in Song 1 of Sappho, poikilothronos (ποικιλόθρον’), I figured out an overall interpretation for this compound adjective, used in Sappho’s song as an epithet that invokes, from the start, the goddess Aphrodite. Here is how I interpreted the first word of Sappho: ‘[I invoke] you [O goddess wearing your dress that is decorated] with varied-pattern-woven magical flowers’. In terms of this interpretation, it would be too simplistic to think of Aphrodite simply as a primal force of nature—as the goddess of sex, of sexuality. She is infinitely more complicated, because she is also a primal force of culture—as the goddess of love driven by sex. This other side of Aphrodite, this complicated side of her primal force, is what I see being conveyed by both the first and the second parts of the compound adjective poikilothronos describing the goddess. The first part, poikilo-, which I have translated as ‘varied’, refers to variety or variability as the essence of Aphrodite: this goddess loves variety. I highlight, for my first example, the love of the goddess for different kinds of flowers in different situations. Her favorites are roses or myrtles or anemones—to name only those variants that I have tracked so far in my essays. And the second part of the compound poikilothronos, which survives independently as the noun throna, is linked with the same kind of love for flowers, since this noun can refer to flowers used as love-charms deployed to attract lovers. Patterns of flowers could be woven into your dress, so that the pattern-weavings could attract visually your would-be lover. Or, the attraction could be olfactory, since different fragrances exhaled by different flowers could become acculturated as the ingredients of different scented oils that you could deploy as perfume not only for your body but even for that special dress you would want to wear at some specially festive occasion.

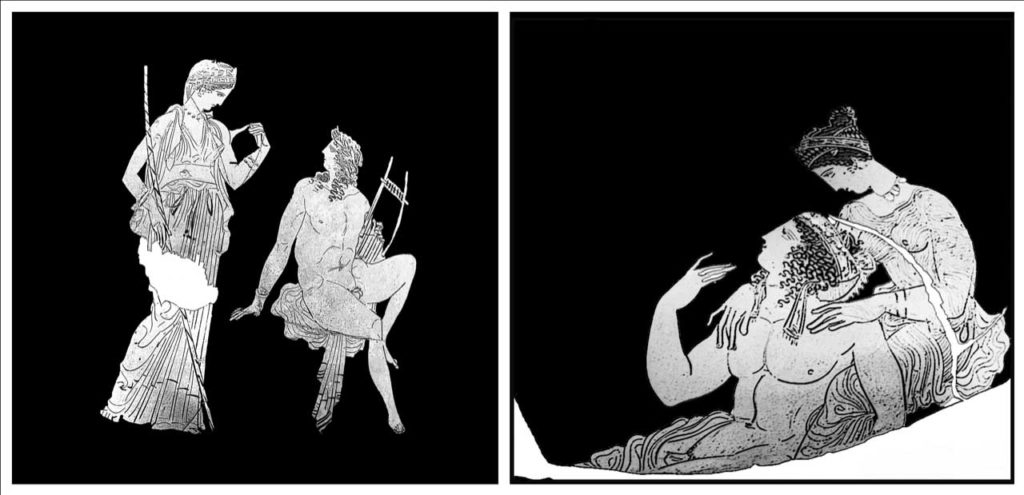

§2. My mentioning of scented oil brings me to Phaon. I focus here on a detail in the myth retold in the songs of Sappho about the love affair of Phaon and Aphrodite—and as further retold by Aelian in his so-called Varia Historia (12.18-19); the retelling is quoted and translated in the previous essay (§17 in Nagy 2021.01.09, linked here). We learn from the retelling by Aelian that Aphrodite had given to Phaon, then an old man, an alabaster-vase containing scented oil to be poured on the skin. The fragrance of the perfume that then pervaded the atmosphere after being rubbed into the skin is what magically transformed the old man, according to the myth, into the most beautiful of young boys. I show a picture of a general scene where we see what happened to Phaon after he was transformed, by the power of Aphrodite, from a decrepit old man into a beautiful young boy. We see the beautiful Phaon enjoying the company of an amorous female beauty. We have seen this picture before, in a previous essay (Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here). In that same previous essay, I also showed a second picture of Phaon in the company of another amorous female beauty (§4 in Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here). I show here again the first of the two pictures:

I focus on the amorous attention that Phaon is receiving from a female beauty—evidently the result of his transformation through the agency of Aphrodite, who is seen overhead as she triumphantly drives off in her chariot pulled by cupids. Earlier, Aphrodite had disguised herself as an old woman and had asked Phaon, then still an old man, to ferry her across a strait. As we read in the version of this story as transmitted by Aelian (again, Varia Historia, 12.18-19), the goddess rewarded the old ferryman by transforming him into a most beautiful boy. I leave aside here other details of the myth, which I collected in an earlier project (Nagy 1973), including a detail about the jealousy felt by Aphrodite at a later point after she eventually realized that all the married women of the city of Mytilene in Lesbos, homeland of Sappho, were lusting after Phaon, and I concentrate here instead on the jealousy felt by the husbands of the women. These jealous men ultimately took revenge and killed the beautiful boy for having affairs with their amorous women.

§3. The scented oil to be poured from an alabaster-vase given by Aphrodite to Phaon is analogous, I think, to a scene in the Lysistrata of Aristophanes, analyzed in the previous essay (§19 in Nagy 2021.01.09, linked here), where the female beauty named Myrrhine / Murrhínē offers to pour scented oil from an alabaster-vase that she brings on-stage, seemingly ready to have sex with her husband Kinesias in return for a suspension of war. But the wife is teasing her husband, withholding sex, because she now interrupts the would-be lovemaking and goes back offstage, up to the acropolis, to rejoin there the women of Athens, who are celebrating the festival of Adonis. Like the women of Mytilene in Lesbos who prefer the boy Phaon to their own men, it seems that Myrrhine prefers Adonis to her husband—at least, at the moment of the festival that celebrates Adonis. What is comical here, however, is that this festival of women—which would customarily take place in different kinds of private settings where different assortments of wives or hetairai could participate—has no place on the acropolis of Athens, which is a public setting. The festival of Adonis does not belong in this most obviously public setting. And we can see something else here that is perhaps even more comical: the role of Myrrhine in the Lysistrata of Aristophanes mimics the role of a hetairā, not the role of a wife. Just to say this much, however, could lead to misunderstandings about the sexuality of wives. In stories about Adonis—and about Phaon—a generic boy-love of Aphrodite would be made all too aware of such misunderstandings. Or, to say it more accurately, the songs of Sappho about the love of Aphrodite for such pretty boys must have shown a keen poetic awareness of such misunderstandings.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.