2021.01.09 | By Gregory Nagy

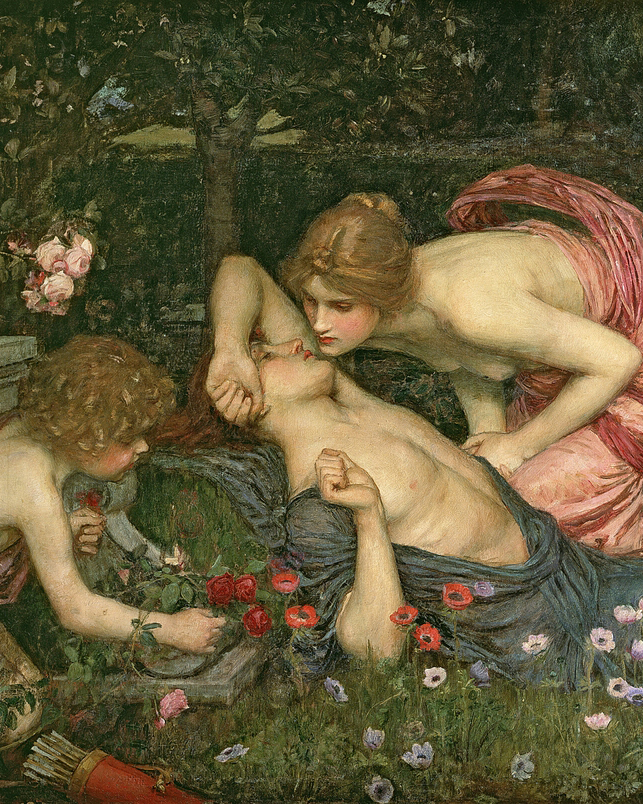

§0. In a previous study, I used the term theo-eroticism as a way of describing a kind of sexuality that gets transformed into something sublime by way of blending eroticism with divinity. In line with terminology used by exegetes of the Bible in their interpretations of some intensely erotic situations pictured in the Song of Songs, I experimented with applying the terms of such biblical exegesis to ancient Greek myths. And, following the biblical model, my experimentation in that study concentrated on the sexuality of “divinity” as a male principle. But what about sexuality as a divinely female principle? In the present study, I will attempt to make up for neglecting, in my previous study, the most obvious exemple of a sexually active female divinity, who is none other than the goddess Aphrodite herself. I will concentrate, however, on only one of the many surviving aspects of myth-making about Aphrodite’s sexuality, which is, the passionate love of this adult female immortal for a pre-adult male mortal, the boy Adonis. The mythical world of this divine love, as I hope to show, was quite real for real people in the real world of pre-modern times, ancient times. When I say “real people” here, I mean people who, back then, actually worshipped Aphrodite as the goddess of love and who would therefore actually think that the various different myths centering on such a divine love were relevant to the various different ritual practices that were intimately connected to their own life-experiences, especially when it comes to love, death, and, possibly, a coming back to life after death—since the ancient myths were telling them about a yearly resurrection of Adonis through the agency of Aphrodite’s love. For them, the boy Adonis could thus be figured as a vital part of an overall model for thinking about their own lives in terms of love, death, and a possible afterlife. In the spirit of such a frame of mind, I start my essay here by showing a modern painting that illustrates, in its own romanticizing way, the theo-erotic power of Aphrodite in bringing Adonis back to life and love. Such power, I must add most emphatically, was already verbalized in the songs of Sappho. And, as we will see, it was also visualized in vase paintings, some of which date back to the Classical era of Athens.

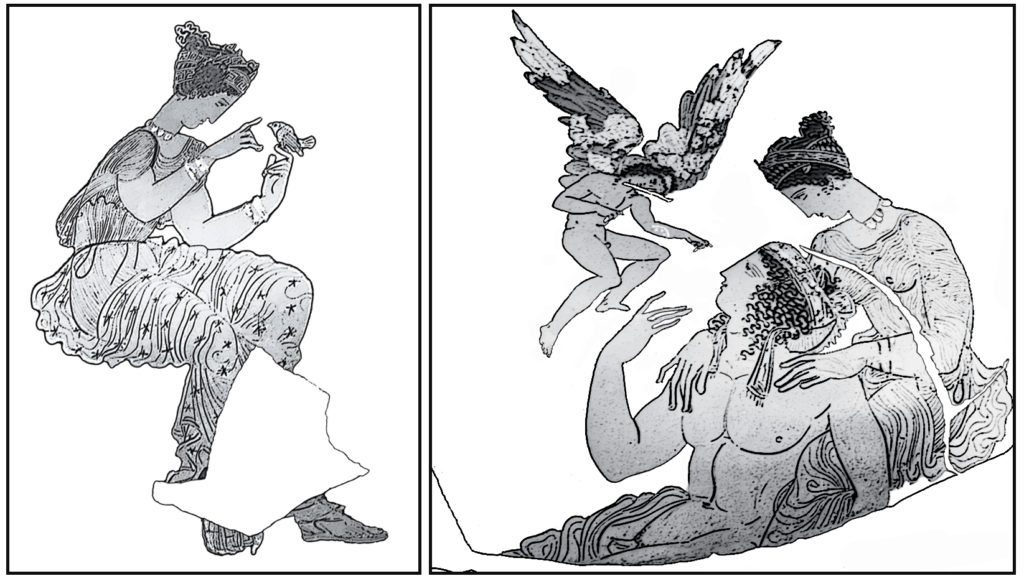

§1. Following up on the modern picture I just showed, I now turn to a comparably erotic ancient visualization that reaffirms, I think, the idea that Aphrodite did indeed bring Adonis back to life—or, to say it more accurately in terms of ritual practices that re-enact myth—that the goddess must bring her boy-love back to life again and again, every recurrent year, since Adonis must die every year, again and again. I will focus on a reference to such a visualization in a Classical Athenian painting that was inspired, as I argued in a previous essay (Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here), by songs of Sappho about Aphrodite’s love for Adonis. It is a painting created in Athens by the so-called Meidias Painter, who lived in the fifth century BCE. I have already shown, in the previous essay just cited (at §5 there), a line drawing of the central erotic scene that is pictured by the painter, and I now show it again here:

But now I also show, by way of two side-by-side line drawings, a closer look at some salient details featured in this erotic scene:

In the left frame we see a female beauty teasing a small bird that is perched on her index finger, and I have already argued, in the previous essay I just cited, that the choreography of her gesture was inspired, as it were, by a poetic moment, now lost, in the songs of Sappho. And then, in the right frame, we see Adonis being caressed from behind by a female beauty who is Aphrodite herself, while a winged Eros is spinning a magic wheel to arouse the love of the languid boy for the goddess. We have seen it all before, in the previous essay. But I draw special attention, this time around, to the attempt of Eros at arousing Adonis with the magic wheel of love, called a iunx, which may be correlated with the kind of little bird that is perched on the other female beauty’s finger—a bird that art historians are tempted to identify with the wryneck, likewise called a iunx (the relevant argumentation of Michael Turner 2005:81 is for me most persuasive). Here too, we have seen it all before—in the essay preceding this one (§5 in Nagy 2020.12.31, linked here). For good measure, however, since the painting of the magic wheel of love is in this case fragmented, I now show a more visible attestation of such a iunx, and we see it being spun here again by a winged Eros:

§2. Having taken a closer look at these details featured in the erotic scene painted by the Meidias Painter, I have by now come to the conclusion that Adonis here is being brought back to life by way of concerted attempts to bring back his sexual desire for the goddess. To put it another way, Adonis is not about to die in this picture. He has already died, and I have in fact already analyzed in previous essays the mourning for Adonis by Aphrodite and by her cupids and by all the female beauties who attend the goddess (I refer especially to §§8–10 in Nagy 2020.11.13, linked here). This is not to say, however, that Adonis will not die again. He will, next year, only to be brought back to life again, next year, and I will have more to say later about the cyclical death and resurrection of this boy-love of Aphrodite. Also, the same can be said for the little bird that is perched on the index finger of the female beauty in this same painting by the Meidias Painter: it too, like Adonis, can die and be mourned and then get resurrected every recurring year. But my point for now is simply this: Adonis is not about to die in the present tense of this picture painted by the Meidias Painter. Rather, he is about to be coaxed back, sexually, into life after death. I see an analogy here with the modern painting that I showed at the start, where Adonis wakes up to life by way of a loving kiss from Aphrodite.

§3. If I am right, then, about the painting by the Meidias Painter, his picture depicts the moment where the mortal Adonis is brought back to life from death. And now I come to a most important point of comparison: there is another picture by the Meidias Painter that depicts the moment where the mortal Phaon is brought back to youth from old age. Again, we have seen it all before: I had shown the picture of a rejuvenated Phaon in the same previous essay (Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here) where I had originally shown the picture of a resurrected Adonis. And now I show that picture of Phaon again here:

§4. The erotic scene that I have just now shown again, where we see a rejuvenated Phaon enjoying the amorous company of a female beauty while Aphrodite, overhead, is driving her chariot pulled by cupids, is evidently inspired by the songs of Sappho—just like the other erotic scene where we see Adonis being caressed back to life by Aphrodite herself. Again, we have seen it all before, in a previous essay that I have already cited (Nagy 2020.10.30, linked here). But there are differences, as we read in a most relevant formulation by the art historian Lucilla Burn (1987:41): “The cult of Adonis probably reached the Greek mainland through Cyprus, with islands such as Lesbos helping in the diffusion of the cult.” This formulation highlights the intermediacy of Lesbos, homeland of Sappho, in diffusing the “cult”—that is, the myths and rituals connected with the figure of Adonis as lover of Aphrodite. And the fact is, as Burn points out (p. 41), that the earliest attestations of the figure of Adonis himself are to be found in the songs of Sappho. But Adonis is not a native son of Sappho’s Lesbos. He is an import from the Near East by way of Cyprus, as Burn has noted in her formulation, and his identity can be traced back from there, all the way back to a most ancient Near Eastern figure, namely, the Mesopotamian (Sumerian / Akkadian) Dumuzi / Tammuz, a youthful male mortal who is every year brought back to life from death by his divine female lover, the goddess Inanna / Ishtar. And here we see a basic difference between Adonis and Phaon, even though their identities are blended in the songs of Sappho. By contrast with the Near Eastern provenance of the myth about the love of Aphrodite for Adonis, there was a “home-grown” myth about the love of Aphrodite for Phaon, as I showed in an early study (Nagy 1973, cited by Burn 1987:42n88). And while the figure of Adonis was a Near Eastern import of great antiquity, the “home-grown” figure of Phaon, native son of Lesbos, was even older. Phaon can be traced even further back in time, back to a prehistoric Indo-European figure whose divine female lover may not even always have been Aphrodite, whose own Cypriote provenance brings her closer, in any case, to the Near Eastern provenance of Adonis. What is more important for now, however, is the simple fact that the provenance of Adonis was from the very start a “foreign” intrusion into the Greek-speaking world, even if it was mediated by way of a blending with what I have described as the “home-grown” provenance of Phaon, who was a mythological native son, as it were, of Sappho’s homeland, Lesbos.

§5. The mythological identity of Adonis as a “foreign” import from the Near East led to the perception of this figure as more “exotic” by comparison with “home-grown” boy-loves of Aphrodite such as Phaon. And this exoticism of Adonis, which was an aspect of his eroticism, inspired a specially powerful charisma of its own, since this particular boy-love of the goddess was, exceptionally for the ancient Greeks, a god in his own right. I have described him already as a pre-adult male mortal. But this description should not be taken to mean that Adonis was a human. No, he was not a human. He was a god. And this “foreign” god was not like the typical Greek gods, who were sky-dwelling immortals. No, Adonis was a mortal god, a dying god. According to various versions of a myth that already existed before Adonis was imported into a Greek context, this mortal god went hunting once upon a time, against the wishes of his goddess lover, and he was gored to death by a mighty boar, as we will see later in a Greek retelling. Further, this pre-existing myth was matched by pre-existing rituals that re-enacted annually the beautiful young god’s death—and his resurrection after death. Thus the exotic as well as erotic Near Eastern prehistory of Adonis inspired a specially powerful charisma of its own, as I was saying, and I am now ready to describe such charisma as a kind of theo-eroticism that is matched by the female lover of this dying god, who is the goddess Aphrodite herself. In terms of such a theo-erotic relationship between Adonis and Aphrodite, any personal engagement with their charisma could be valued as a luxury—as a kind of ‘luxuriance’ that we see being signaled by the word (h)abrosunē in the celebrated wording of Sappho (Π2 25–26 = Fragment 58.25–26 ed. Voigt, as analyzed in my earlier work, at §§29–31 in Nagy 2019.03.08, linked here). A visual sense of such luxuriance is I think well represented in two Renaissance paintings that I show here.

§6. My formulation of ‘luxuriance’ leads me now to think about the actual use of the two Classical Athenian vases considered so far, both of which are graced with paintings by the Meidias Painter. As we have seen, the central erotic theme in one of these painted pictures was the resurrection of Adonis by way of sexual arousal through the agency of Aphrodite, and, in the other, it was more simply the rejuvenation of Phaon by Aphrodite. Both of these erotic themes, driven by the primal sexuality of Aphrodite, involved a sense of ‘luxuriance’, as I argue—especially in the case of Adonis, whose exotic Near Eastern provenance made him seem all the more ‘luxuriant’—theo-erotically luxuriant. But this theo-erotic kind of luxuriance, on a mundane level, would have been as expensive as it was chic. In this essay, I propose to connect the worldliness of the materialistic observation I just made by taking a good hard look at the expensiveness of acquiring such vases as painted by the Meidias Painter.

§7. And here I return to a basic fact about both of the vases I have considered so far. These expensive pieces of art were buried in the same tomb, together with the dead body of the person who presumably owned these precious objects. So, what is the connection between these expensive works of art, produced in Athens, and the presumably wealthy Etruscan in North Italy who owned them and was eventually buried with them?

§8. I can ask the same kind of question about less prestigious precious objects, such as the vases produced locally in South Italy many years later, mostly in the fourth and the third centuries BCE—and we would expect that these vases too had been buried with their owners. I have shown an example in a previous essay (Nagy 2020.12.25, linked here): it is a vase graced with a painting that pictures a profile of Aphrodite paired with a magnified wryneck and with a miniaturized rose, that is, with a rosette, and I show the picture again now:

§9. Keeping in mind this example of South Italian art, I now return to the so-called Pagenstecher Lekythoi of South Italy, as I referred to them in another previous essay (at §14.1 in Nagy 2020.12.31, linked here). In the context of that referemce, I quoted a relevant formulation from Michael Turner (2005:66, with extensive bibliography) about these lekythoi: “they were containers for rose oil” (p. 66, following Rolf Hurschmann 1997:7). And now I quote what Turner also says (again, p. 66) about such oil vessels: “they were […] made and decorated for the grave.” Yes, I agree. But I would add that these same lekythoi were originally made and decorated for the living. As you were living out your life in your own lifetime, you would surely take delight in the fragrance of the rose-scented oil whenever you poured some of it from those pretty lekythoi and rubbed it into the skin. I am thinking here of those happy times when you were, yes, still very much alive, before you ever went to the grave. If you were, say, an elegant lady, old or young, who loved luxury, you would be scenting yourself on festive occasions with rose perfume that you would pour on your skin from your very own Pagenstecher Lekythos. And you would want to take this beloved Lekythos of yours with you to the grave, when the time comes. After all, who knows? Maybe the rose-scented oil inside the Pagenstecher Lekythos that is buried with you in your tomb could somehow help you come back to life again someday? And there would be the model of Adonis himself. After all, he came back to life after death. Or, to say it another way, Adonis comes back to life every year.

§10. The reverie that I have fancifully reconstructed here depends on a well-known myth about the death and resurrection of Adonis as the boy-love of two rival goddesses, Persephone and Aphrodite. As we read in such sources as the Library of “Apollodorus” (3.14.4 ed. Frazer 1921), Adonis dies every year and then, afterwards, he comes back to life every year—but he is allowed to rejoin in life his loving mistress, Aphrodite, only after spending an allotted span of time in death with his other loving mistress, Persephone, goddess of the dead.

§11. So, what does this well-known myth about the yearly death and resurrection of Adonis have to do with the Pagenstecher Lekythoi? For an answer, we must consider again the flower that gives its overpowering scent to the oil contained in these lekythoi. That flower is the rose. And the rose is the answer to our question, since it is so intimately connected with Adonis. As we read in the poem Lament for Adonis, by Bion of Smyrna (second / first century BCE), the very first rose that ever blossomed in this world had originated from the blood of Adonis—after a mighty boar that he was hunting gored him in the thigh with his tusk, so that the boy bled to death. We read about it at lines 64–66 of the Lament.

§12. But there is more to it. The blood of Adonis is connected to the love of Aphrodite. I focus here on a detail in the Lament of Bion, at lines 6–14. We read here that blood was pumping out of the gash in the thigh of Adonis before the moment of his death, but it stopped flowing when that moment finally arrived, and now the blood was drained even from his rosy lips when, at the very moment of death, Aphrodite kissed those lips of his for the last time—or, as we are about to see, maybe not at all for the last time ever. Here are the lines from the Lament of Bion, 6–14, followed by my working translation:

αἰάζω τὸν Ἄδωνιν· ἐπαιάζουσιν Ἔρωτες.

κεῖται καλὸς Ἄδωνις ἐν ὤρεσι μηρὸν ὀδόντι,

λευκῷ λευκὸν ὀδόντι τυπείς, καὶ Κύπριν ἀνιῇ

λεπτὸν ἀποψύχων· τὸ δέ οἱ μέλαν εἴβεται αἷμα

{10} χιονέας κατὰ σαρκός, ὑπ’ ὀφρύσι δ’ ὄμματα ναρκῇ,

καὶ τὸ ῥόδον φεύγει τῶ χείλεος· ἀμφὶ δὲ τήνῳ

θνᾴσκει καὶ τὸ φίλημα, τὸ μήποτε Κύπρις ἀποίσει.

Κύπριδι μὲν τὸ φίλημα καὶ οὐ ζώοντος ἀρέσκει,

ἀλλ’ οὐκ οἶδεν Ἄδωνις ὅ νιν θνᾴσκοντ’ ἐφίλησεν.

I cry aiai—I make this lamenting cry for Adonis. And lamenting in response are the Cupids [Erōtes].

[He lies there, dead,] the beautiful Adonis is lying there. In the mountains—his thigh, the [boar’s] tusk

—the gleaming-white tusk had struck his gleaming-white thigh, and, for Aphrodite, he [now] makes-passionate-pain [aniân] for her [to feel],

as he oh-so-delicately [leptón] breathes-out-his-breath-of-life, and, with his dark blood running down

{10} his snowy flesh, his eyes, as they look up from under his brow, are-glazing-over [narkân].

Now the rose [rhodon] escapes from his lip, and on that lip

dies also the kiss that Aphrodite will maybe-never [mē-pote] carry-off-as-a-prize.

For Aphrodite the kiss—even though he is now not alive—gives delight,

but he does not know, Adonis does not, that she, as he dies, has just kissed him.

(At the last line, I prefer the manuscript reading θνᾴσκοντ’ ἐφίλησεν, not the emendation θνᾴσκοντα φίλησεν, since the augmented form conveys, in imitation of Homeric diction, I think, a perfective side-meaning for the aorist: ‘has just kissed’ not simply ‘kissed’.)

§13. These lines from the Lament for Adonis by Bion are quoted by Michael Turner (2005:68, where he uses the edition and the accompanying translation of Bion by J. D. Reed 1997). According to Turner (p. 68n67, following Reed p. 201), the blood of Adonis at line 11 of the Lament by Bion is a rhodon ‘rose’ simply because the lips of Adonis once had a rosy color—before the blood was drained out of them by death. While I agree that the poetry of Bion has metaphorized here the mythological idea that the blood of Adonis was transformed into the very first rose that ever blossomed in our world, I still prefer to interpret the rose at line 11 of Bion as mythologically the same “real” blood that was “really” circulating in the body of Adonis until it got drained out, even from his lips, through the open wound of the gash inflicted by the boar’s tusk. My interpretation is supported, I think, by the existence of variant myths about the death of Adonis, where the blood that flows from the open wound of this boy-love of Aphrodite is transformed not into a rose, which is what we read at line 66 of the Lament by Bion, but into other flowers, such as the anemṓnē or ‘wind-flower’ (as we read in Scholion 831 for line 26 of Lycophron, Alexandra; also in the Scholia for line 92 of Idyll 5 of Theocritus; the story is most memorably narrated in Ovid’s Metamorphoses 10.731–739; extensive documentation of the primary sources by Reed 1997:233).

§14. And there also existed, I think, a variant myth where the blood of Adonis was transformed into the flower of a myrtle-tree. In this case, although we have no direct evidence, the indirect evidence is of great antiquity. I start with a report by Pausanias (6.24.6-7), analyzed in my previous essay (Nagy 2020.12.31, linked here), about the connections of Aphrodite and Adonis, as a pair, with myrtles as well as roses. As Pausanias says, the statues of the Kharites or ‘Graces’ that he sees in the agora of the people of Elis are linked with roses and myrtles, since one of the three ‘Graces’ is represented as holding a rose while another of the three is holding a spray of myrtle. In the case of the mursínē or ‘myrtle’, as Pausanias calls it, I find it significant that the word kharis itself, which applies generically in this context to each one of the three ‘Graces’, can apply in other contexts specifically to the flower of the myrtle-tree. I quote from Scholia D (via Scholia A) for Iliad 17.51: Μακεδόνες δὲ καὶ Κύπριοι χάριτας λέγουσι τὰς συνεστραμμένας καὶ οὔλας μυρσίνας, ἃς φαμὲν στεφανίτιδας ‘Macedonians and Cypriotes use the word kharites [= plural of kharis] with reference to myrtle blossoms that are compacted and curled [around a garland]. We call them garland-blossoms [stephanitides]’ (from my MoM 4§§144–146; further comments in HPC II§424 pp. 295–296). Such a specific use of plural kharites in referring to myrtle blossoms is attested already in the Homeric Iliad (as I argued in HPC II§424 pp. 295–296). In Iliad 17.51–52, where the death of the hero Euphorbos is described, we see droplets of blood that grace the disheveled hair of the dead hero, lying in the dust, and these droplets are actually compared by way of simile to kharites, which in this context seem to be referring to red blossoms of myrtles: αἵματί οἱ δεύοντο κόμαι χαρίτεσσιν ὁμοῖαι | πλοχμοί θ’. Here is my translation: ‘with blood bedewed were his locks of hair, looking like kharites, | with the curls and all’. I draw attention here (following my comment in HPC II§425 p. 296n80) to a modulation from red to white coloring in the complex simile of Iliad 17.51–59, where the graphic description extends from lines 51–52, focusing on the red color of myrtle blossoms, to lines 53–59, focusing on the white color of olive blossoms.

§15. Coming back to the death of Adonis that the poetry of Bion describes at lines 6–14 in the Lament, I must add now a further comment—about the actual loss of blood experienced by the dying boy. His blood is flowing freely out of the open wound in his thigh, and, by the time the boy finally dies, all the blood has been drained out of his body. So, the circulation of blood in the boy’s lips has already stopped cold by the time that Aphrodite presses her own lips against them. The boy’s lips kissed by the lips of the goddess are by now dead white, having lost the vibrant redness of roses. The circulation of blood in the boy’s lips has already been sucked out of him when Aphrodite presses her own rosy lips against his. His lips, now white with the coldness of death, have been made ready for kisses from that other mistress of his, Persephone. But the realism of the poet’s colorful imagination here has a happy as well as a sad side to it, since Adonis will have his life restored when he is kissed again by Aphrodite, come springtime. By then, the circulation of his life-blood will be fully restored. And, if you are reading Bion, you can anticipate such a renewal of life and love simply by reading his poetry, without even having to wait for spring to come.

§16. In the Lament by Bion, the story about the death and resurrection of Adonis is on hold at the point where the boy-love of Aphrodite dies while being passionately kissed on the lips by the goddess, but the myth lives on, since the ritualized yearly death of Adonis will be followed by a correspondingly ritualized yearly resurrection, which in turn will make the kiss of Aphrodite on the lips of Adonis come alive, just as Adonis himself will come alive. And those lips, kissed by Aphrodite at the moment of his death, will now exude not blood but the primal essence of roses—the kinds of roses that become the ingredients of the perfume to be rubbed into your skin after you pour over your body the precious scented oil that you store inside such delicately decorated little vases as the Pagenstecher Lekythoi.

§17. In the so-called Varia Historia of Aelian (12.18-19), who lived in the second / third century CE, we find a synopsis of a myth that contains a most relevant piece of comparative evidence, and I quote here the text of that myth, followed by my working translation:

{12.18} Τὸν Φάωνα κάλλιστον ὄντα ἀνθρώπων ἡ Ἀφροδίτη ἐν θριδακίναις ἔκρυψε. λόγος δὲ ἕτερος ὅτι ἦν πορθμεὺς καὶ εἶχε τοῦτο τὸ ἐπιτήδευμα. ἀφικνεῖται δέ ποτε ἡ Ἀφροδίτη διαπλεῦσαι βουλομένη, ὃ δὲ ἀσμένως ἐδέξατο, οὐκ εἰδὼς ὅστις ἦν, καὶ σὺν πολλῇ τῇ φροντίδι ἤγαγεν ὅποι ποτὲ ἐβούλετο. ἀνθ’ ὧν ἡ θεὸς ἔδωκεν ἀλάβαστρον αὐτῷ, καὶ εἶχεν αὕτη μύρον, ᾧ χριόμενος ὁ Φάων ἐγένετο ἀνθρώπων κάλλιστος· καὶ ἤρων γε αἱ γυναῖκες αὐτοῦ αἱ Μυτιληναίων. τά γε μὴν τελευταῖα ἀπεσφάγη μοιχεύων ἁλούς. {12.19} Τὴν ποιήτριαν Σαπφώ, τὴν Σκαμανδρωνύμου θυγατέρα, ταύτην καὶ Πλάτων ὁ Ἀρίστωνος σοφὴν ἀναγράφει. πυνθάνομαι δὲ ὅτι καὶ ἑτέρα ἐν τῇ Λέσβῳ ἐγένετο Σαπφώ, ἑταίρα, οὐ ποιήτρια.

{12.18} Phaon, the most beautiful of all humans, was hidden away by Aphrodite in a patch of lettuce. And there is another tale that is told about him… That he was a ferryman, and this was his vocation. And, once upon a time, Aphrodite [in disguise] comes to him and says that she wants to make a crossing by way of the ferry. He gladly [asménōs] received [the request], without knowing who she was. With the greatest care, he transported her to wherever it was she wanted to go, and, in return for this, the goddess gave him a vase-made-of-alabaster [feminine noun alábastros], and it contained scented-oil [múron]. Phaon anointed himself with the oil and became the most beautiful of all humans. So, all the wives of the men in Mytilene [in Lesbos] were lusting [erân] after him, and, in the end, he was caught in the act of adultery and slaughtered. {12.19} About the poetess Sappho, daughter of Skamandronymos… even Plato, son of Ariston, ascribes to her the title sophē ‘wise’ [paraphrase here from Plato’s Phaedrus, 135bc], though I am told there was also another Sappho in Lesbos, a courtesan [hetaírā], who was not the same person as the poetess.

The mention here of Aphrodite’s gift to Phaon, an expensive alábastros ‘alabaster-vase’ containing múron ‘scented oil’ for rubbing into the skin, is for me reminiscent not only of the Pagenstecher Lekythoi. If we go further back in time to the era of Classical Athens, we find another alabaster-vase mentioned—in the context of an ongoing seduction scene. It happens in the Lysistrata of Aristophanes, where we read (at line 947) the word alábastos (a variant reading alábastros is also attested in the textual transmission). Here too, the alabaster-vase is a container of scented oil—here too, as in the text of Aelian, the word for this oil is múron (at lines 942, 944)—and its perfume is to be released into the air during a seduction arranged by a would-be seductress named Murrhínē, whose name is a personification not only of the myrtle-flower but also, most comically in this erotic context, of female genitalia, as I pointed out in the previous essay (§14.2 in Nagy 2020.12.31, linked here).

§18. The eroticism of this context in the comedy of Aristophanes can help us appreciate why Aelian makes such a guarded remark about Sappho, who is surely the source of the story he tells about Phaon. This pretty-boy, as we can see in Classical Athenian vase paintings, rivals Adonis himself as the love-object of Aphrodite. So, surely the Sappho who tells suggestive stories about the scented oil that is rubbed into the skin of Phaon cannot be the same Sappho as that oh-so-respectable lady who is oh-so-admired by Plato: surely, instead, this other Sappho must be a hetaírā, a courtesan. So much for the guardedness. But what are we to think, today, about the affinities of such a world of hetairai with the provocative eroticism of mythological figures such as Phaon or Adonis in the songs of Sappho and in the later reception of such songs? My answer is that the world of hetairai, as I hope to show in an essay still to come, can converge with the world of oh-so-respectable wives and mothers and daughters and sisters—in the perfumed atmosphere of myths about the likes of Phaon or Adonis.

§19. For now, in any case, I could content myself with asking just one more question before I finish considering here such a perfumed atmosphere: in the Lysistrata of Aristophanes, what was the scent of the scented oil contained in the alabaster-vase that ‘Little Myrtle’, the would-be seductress named Murrhínē, had brought on-stage as the perfume that would lead to seduction? There is one point in the comedy, at line 944, where ‘Little Myrtle’ cries out in mock-innocence, and I paraphrase: “oh, so you don’t like the smell of the múron ‘scented oil’ that is rhódion?—in that case I’ll run back off-stage and bring back for you from there some other scent that you would maybe like better?” She then runs off, off-stage, and of course she never comes back on-stage, so that the seduction never happens. But the question remains, what was the scent of that scented oil that ‘Little Myrtle’ describes as rhódion? I propose an emendation here. We may read here rhódinon (ῥόδινον), meaning ‘made from roses’, instead of the reading that we find attested in the textual transmission, Rhódion (῾Ρόδιον) meaning ‘from [the island of] Rhodes’. I am hardly the first to conjecture rhódinon instead of Rhódion, as readers of the received text of Aristophanes can see for themselves in the apparatus criticus of older editions: Theodor Bergk, in an early two-volume Teubner edition of Aristophanes (published and republished multiple times, starting in the mid-nineteenth century) had already conjectured the possible reading: “fort[asse] ῥόδινον.” In any case, the opportunity for seduction, I would surmise, could have been most favorable in this comic scene if the scent of the oil in this context was really perfume extracted from roses, but such an opportunity now vanishes most comically into thin air—along with the lady named ‘Little Myrtle’, who is the embodiment of the scent emanating from her. This fictive lady’s own scent could have translated into the fragrance of roses, if she had ever applied the content of the alabaster-vase that she had brought on-stage. But her real scent, to start with, would have been the fragrance of real myrtle-scented oil. Things would be different, of course, if ‘Little Myrtle’ had been a real woman and not a comic fiction. After all, there are many attestations, especially in Attica, of real women whose name happened to be really Murrhínē (IG II² 5492, IG II² 6335, and the list goes on). In “real life,” then, this name Murrhínē, which really does mean ‘myrtle’, would be simply a metaphor: to name a girl ‘Myrtle’ at birth would be to give her, simply, a beautiful name. A real woman could of course smell like a myrtle if she chose to perfume herself with myrtle-scented oil, but she could just as easily smell like a rose if she chose a rose-scented oil, or, much more simply, she could forgo perfume and just smell like her natural self. By contrast, the fictionalized ‘Little Myrtle’ of Aristophanes could actually personify real perfume, that is, real myrtle-scented oil. It almost goes without saying, but some commentators have insisted on saying it, that the scented oil offered by the seductress for pouring on the skin could thus be useful as a lubricant for her as also for her would-be sexual partner. Or, if we keep thinking of this woman named Murrhínē as a personification of the flower, then the scented oil of such a personified Myrtle could represent the natural scent of a real myrtle that has become personified as an earthy natural woman.

§20. All this talk about scent, both artificial and natural, brings me back full circle to the theo-eroticism, as I have been calling it, of Aphrodite herself. In the previous essay, I already argued that this goddess identifies with the widest variety of flowers, and of scents of flowers, just as she identifies with the widest variety of birds, ranging from earthy sparrows to celestial swans. And now, back to flowers… It only follows, at this point, that I should concentrate on the theo-eroticism of Aphrodite in her identifying with the fragrances linked with her flowers. Instead of looking further, however, at all the varieties of flowers—which naturally connect with all the varieties of all the fragrances exhaled by these flowers—I now concentrate only on the simple reality of variation in fragrance. And, in attempting to express such a reality, I can already say that the theo-eroticism of Aphrodite is perhaps most easily grasped by way of sensing, simply, that she smells good.

§21. How to express such a sense, that the essence of theo-eroticism is most easily grasped in its fragrance? Here I come back to a detail from my previous study of theo-eroticism, where I noted a rather telling observation, however superficial, about the male divinity who was singled out by Homer as an ultimate model of theo-eroticism. In that study, Masterpieces of Metonymy (Nagy 2016|2015, abbreviated as MoM), I quoted what Homer actually said about such a model. But this Homer was not the Homer of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey. He was Homer Simpson. This other Homer was talking about an epiphany he experienced at a moment when he thought he was about to die or was in fact already dead, and the divinity who miraculously appeared to him at this moment was “God.” Our latter-day Homer describes his latter-day experience of divinity in a most revealing way, and I quote here the exact words spoken by Homer Simpson himself in describing his near-death vision of God (MoM 1§153): “Perfect teeth. Nice smell. A class act, all the way.” (The quotation is from an early episode in the series The Simpsons, “Homer the Heretic,” season 4, episode 3; originally aired 1992.10.08; written by George Meyer, directed by Jim Reardon.)

§22. The playful quotation of Homer’s words in my study had been situated within the framework of a serious argument, however: I was comparing the divine “class act” of an epiphany experienced by Homer with another divine epiphany. In this case, the epiphany was reportedly experienced by the Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus, head of the reconstituted Academy in Athens as it existed in the fifth century CE. In the case of Proclus, as we read in a narrative about his life and times, written by his successor at the Academy, a Neoplatonist named Marinus (Life of Proclus section 30), the epiphany that our philosopher experienced happened within a dream in which he saw a sublime vision of ‘an Athenian lady’—the expression used here is κυρία ᾿Αθηναΐς, which connotes in late antique phases of the Greek language a most elevated aura of aristocracy—and this aristocratic lady turned out to be none other than Our Lady of Athens, the goddess Athena herself, in her role as patroness of philosophy. In the philosopher’s dream, Our Lady was telling him that she wanted to live with him forever. End of dream. Now Proclus wakes up, and he is informed that, while he was sleeping and dreaming, the statue of Athena Parthenos up on the acropolis had been carted off by Christian fanatics who tore her away from her sublime residence in the Parthenon. She was never to be seen again. But at least our philosopher could now console himself, having just experienced an epiphany of Athena, that this goddess will stay alive in his heart forever.

§23. In my earlier work on theo-eroticism, then, the only female example I highlighted was the goddess of intellect, Athena. My choice in that work, dictated as it was by a Neoplatonist, was a beautiful choice, yes, but the theo-eroticism of this sublimely beautiful aristocratic lady was, shall we say, sublimated. By contrast, however, I can now make up for such a sublimation of sexuality in that context but focusing, in the present context, on another sublimely beautiful aristocratic lady, another ancient resident in the city of Athens, who is the goddess Aphrodite herself. And the captivating sensuality of this divine female beauty is fully sensed if we recall Homer’s words: “Perfect teeth. Nice smell. A class act, all the way.” The “nice smell” of Aphrodite can be sensed, in all its fragrance, at the exact moment when the words of Sappho in her Song 1 evoke the goddess: at that moment, the Lady is seen wearing a dress interwoven with a riotous variety of flowers that are surely as fragrant as her own body must be fragrant. But what about the teeth of Aphrodite? Are they perfect? I can only guess, but it gives me delight to hear, in Song 1 again, that Sappho is right now looking at the smiling face of Aphrodite. That is a good sign. As the goddess looks back, I hope that her perfect teeth will be visible with the parting of the smiling lips that are always ready to kiss, like rose petals, the ready lips of Adonis.

For bibliographical references, see the dynamic Cumulative Bibliography here.