2020.11.13 | By Natasha Bershadsky

§0. I pick up here the thread of an essay by Gregory Nagy where he connects a vase painting that pictures a girl with a little pet bird, as painted by the Meidias Painter, with Poems 2 and 3 of Catullus. I will argue that there is a poetics of fluidity in identifying this little bird, and that the identities of such birds actually depends on this fluidity.

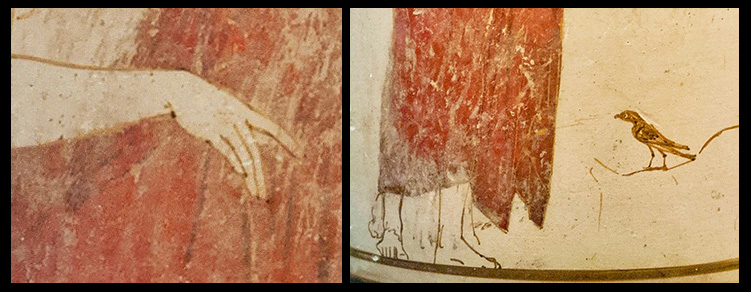

§1. The similarity between Lesbia and her pet in Poem 2 of Catullus and a lady with a small bird as painted on a hydria by the Meidias Painter (Florence, Museo Archeologico 81948) was observed a long time ago. In a 1949 paper, Francis Lazenby wrote: “The very lovely scene on a vase in the style of Meidias, in Florence, tempts one to imagine that the artist has baked into pottery his portrait of the beauteous Lesbia playing with her pet. She holds a small bird on the index finger of her left hand, and is preparing to stroke its beak with her other hand.”[1]

§2. The bird in Poem 2 of Catullus is a passer, which is usually translated as ‘sparrow’. However, the discussion of the precise identity of passer was extensive enough for one researcher to lament the “quest for the historical passer[,] which has led scholars on a wild chase through the vastness of the Alps and elsewhere in tracking down the exact nature of the bird.”[2] If we think of the Latin word passer diachronically, we see the meaning mutating from general, to specific, and back to general: passer can be reconstructed as Indo-European *peth₂-/*p(e)t-tro-s, that is, a ‘flying thing’, and then we can “fast-forward” from the Latin derivative passer to Italian passero, which means ‘sparrow’, while Spanish pájaro is a generic ‘bird’.

§3. The word passer in Poems 2 and 3 of Catullus is often connected to birds called in Greek strouthoi, which draw Aphrodite’s chariot in Sappho 1.10.[3] Strouthos is also predominantly translated as sparrow, but the sparrow seems to be only the most salient representative of strouthoi: we can compare the modern taxonomy, according to which the house sparrow is the type species for the genus passer. Strouthos mostly referred to birds of that genus; but, along with its diminutive, strouthion, it could also be used generally for a little bird.[4]

§4. Let us now focus on the vases and their birds. The birds that perch on the index fingers of elegant women as painted on vases are certainly passerines; beyond that, the identification is difficult. However, perhaps such broader identification is more in line with ancient perceptions of small birds. Many little birds were loved. Let us start with the enigmatic elaios (‘wild-olive bird’), who received a funerary epigram in the Greek Anthology (7.199, by Tymnes):

Ὄρνεον ὦ Χάρισιν μεμελημένον, ὦ παρόμοιον

ἁλκυόσιν τὸν σὸν φθόγγον ἰσωσάμενον,

ἡρπάσθης, φίλ᾿ ἐλαιέ· σὰ δ᾿ ἤθεα καὶ τὸ σὸν ἡδὺ

πνεῦμα σιωπηραὶ νυκτὸς ἔχουσιν ὁδοί.

Bird, nursling of the Graces, who did modulate

your voice till it was like a halcyon’s,

you are gone, dear elaios, and the silent ways of night possess

your gentleness and your sweet breath.[5]

§5. Looking up this word elaios, we discover that the bird had other names. Here is the report by Athenaeus 2.69:

συκαλίδες. Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μύνδιος ἱστορεῖ: ‘ἅτερος τῶν αἰγιθαλῶν ὑφ᾽ ὧν μὲν ἔλαιον καλεῖται, ὑπὸ δέ τινων πυρρίας: συκαλὶς δ᾽, ὅταν ἀκμάζῃ τὰ σῦκα.’ δύο δ᾽ εἶναι γένη αὐτοῦ συκαλίδα καὶ μελαγκόρυφον. Ἐπίχαρμος: ‘ ἀγλαὰς συκαλλίδας.’ καὶ πάλιν

ἦν δ᾽ ἐρῳδιοί τε πολλοὶ μακροκαμπυλαύχενες

τέτρακές τε σπερματολόγοι κἀγλααὶ συκαλλίδες.

ἁλίσκονται δ᾽ αὗται τῷ τῶν σύκων καιρῷ, διὸ βέλτιον ὀνομάζοιτ᾽ ἂν δι᾽ ἑνὸς λ: διὰ δὲ τὸ μέτρον Ἐπίχαρμος διὰ δυεῖν εἴρηκεν.

And Alexander the Myndian asserts—“One of the tits is called by some people elaios, and by others purrias (‘redhead’); but when the figs become ripe, it gets the name of sukalis (‘fig-eater’).” And there are two species of this bird, the sukalis and the melankoruphos (blackcap). Epicharmus spells the word with two ll, and writes sukallides. He speaks of beautiful sukallides: and in a subsequent passage he says—

“And herons were there with their long bending necks,

And grouse who pick up seed, and beautiful sukallides.”

§6. The steps that rapidly lead from elaios to sukalis can make us dizzy; but, interestingly, the landing point is not too far from the world of the Meidias Painter, with its aura of a preparation for a wedding. The quotation above from Epicharmus comes from his comic play called The Wedding of Hebe. We lack the context (and apparently the play was full of fish and eros[6]); yet, I note that the two birds that are mentioned, the heron and the grouse, are the most frequent, and probably significant, avian presences in domestic scenes on vases that broadly can be identified as preparations to (sometimes still distant) weddings.

§7. We learn more about the mysterious transformation of sukalis (beccafico) to melankoruphos (blackcap) from Aristotle, who describes it among several examples:

ὡσαύτως δὲ καὶ αἱ συκαλλίδες καὶ οἱ μελαγκόρυφοι· καὶ γὰρ οὗτοι μεταβάλλουσιν εἰς ἀλλήλους. γίνεται δ᾿ ἡ μὲν συκαλλὶς περὶ τὴν ὀπώραν, ὁ δὲ μελαγκόρυφος εὐθέως μετὰ τὸ φθινόπωρον. διαφέρουσι δὲ καὶ οὗτοι οὐθὲν ἀλλήλων πλὴν τῇ χρόᾳ καὶ τῇ φωνῇ. ὅτι δ᾿ ὁ αὐτός ἐστιν ὄρνις, ἤδη ὦπται περὶ τὴν μεταβολὴν ἑκάτερον τὸ γένος τοῦτο, οὔπω δὲ τελέως μεταβεβληκότα οὐδ᾿ ἐν θατέρῳ εἴδει ὄντα.

Similarly the beccafico and the black-cap: these too change into each other. The beccafico occurs about the fruit season and the black-cap immediately after the autumn. These too differ from each other in no respect except colour and voice. That they are the same bird has been shown by observing each kind at the time of the change, when they have not yet completely changed and are not in one or the other form.

(History of Animals 632b-633a)

§8. Thus, a small bird can change its voice, its color, and its diet, according to the season, and yet notionally remain the same bird. I suggest that such a concept is parallel to the lifecycle of a girl, who is transformed into a bride and then into a woman.

§9. But sometimes a more terrible transformation happened, that of death, either of a girl or of a bird. Let us return to the namesake of sukalis, the elaios, and the funerary epigram by Tymnes. We see here yet another dimension of change: the bird could modulate its voice to sound like a halcyon. The halcyon is a fabulous bird, known for his mournful voice; it is often compared and confused with the nightingale.[7] The epigram describes the voice of elaios proleptically, as if the bird were mourning its own death. The epigram also brings us back to the world of the Meidias Painter. The elaios is described as having been taken care of by the ‘Graces’ or Charites (Χάρισιν μεμελημένον). Now, the personifications we see painted by the Meidias Painter— those beautiful girls with names like Eudaimonia, Paidia, and Pannychis—were collectively identified by Gloria Ferrari as ‘Graces’ or Charites.[8] The little bird perched on the finger of Eurynoe (Florence 81948) finds a parallel in the dead elaios, who had been nurtured, as we have read in the text quoted above, by the Graces themselves.

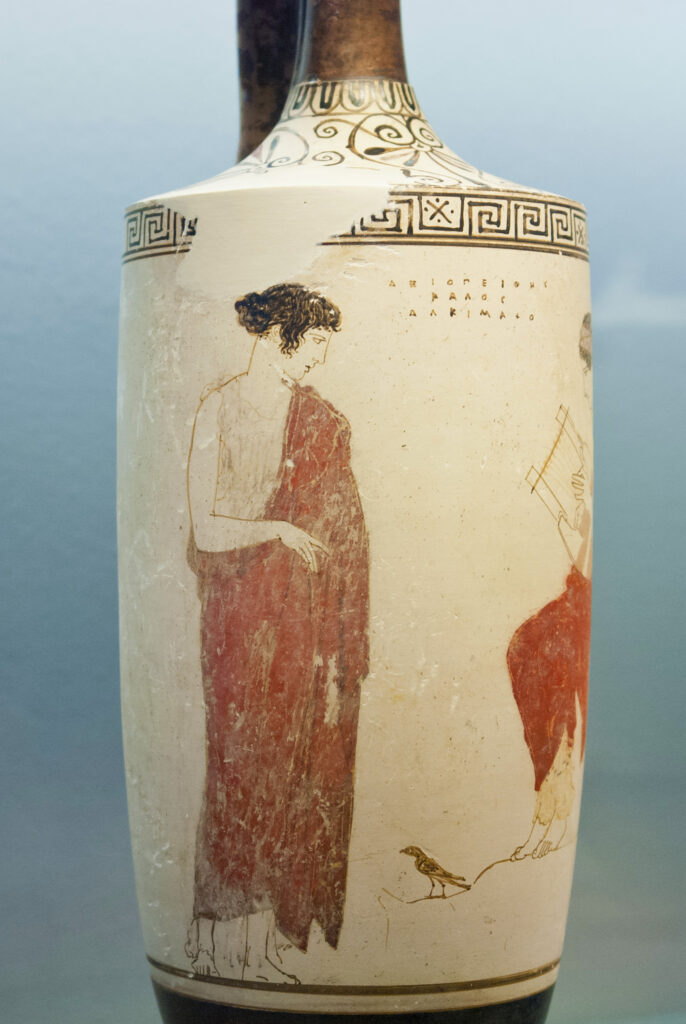

§10. Here we can observe a strand of sadness that seems to be present in the beautiful celebrations depicted by the Meidias Painter: the main figures on Florence 81947 and 81948 are Phaon and Adonis, figures who both have tragic associations, sounded in the poetry of Sappho and in her vita tradition; the genre of wedding laments provides a bittersweet parallel. But the scenes of festivities, associated with preparations for a wedding, can be also transposed to a somber context, appearing on the white-ground lekythoi, vases that are primarily funerary. Birds follow the women: we see a white, fragile heron standing between two women who hold a phlemochoe and a chest;[9] another heron, thin and black, accompanies a girl who is holding a garland.[10] These are the scenes of past happiness that now sting. And the encounter of the divine girls, with their music-making, is also transferred to a funerary white-ground lekythos: in a celebrated vase painting by the Achilles Painter, we see a beautiful young woman playing on a phorminx, while another stands in front of her; their location is labelled Helicon.[11] A little bird perches on the rocky ground between them. The standing girl is resplendent in her red himation; yet, her expression is mournful. Looking closer, we see that the index finger of her right hand is lifted up, in a gesture that exactly parallels the gestures of the happy girls with their pet birds: she offers her finger for the bird to perch on, but it stays on the ground. Who is this bird? A sparrow of desire, a nightingale of longing?[12]

[1] Lazenby 299.

[2] Brenk 703, summarizing Quinn 381.

[4] Arnott 330, Lewis and Llewelyn-Jones 484.

[5] Translation, modified, via the Loeb Classical Library.

[6] On The Wedding of Hebe, see Marta Cardin and Olga Tribulato.

[7] Olga Levaniouk (2011), chapter 17.

[8] Ferrari 46.

[9] Athens, National Museum, CC1628; Beazley 213944.

[10] Taranto, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, 20309, Beazley 208170.

[11] Nagy 2019.02.14 identified the phorminx-player as Sappho.

[12] Sappho fr. 136.